“Challenger, this is Houston,” astronaut Mary Cleave called up from the ground in Mission Control. “How do you read?” Mary was one of NASA’s newest astronauts, who’d been selected in a fresh batch of recruits picked in 1980. The latest group had included another woman, too: Bonnie Dunbar, who’d been an engineer at JSC before her selection. Now, with their addition, there were eight women in the astronaut corps.

“I can hear you, Mary,” Sally Ride responded from space.

“Good evening, Sally. Sorry to wake you up,” Mary said. She proceeded to give Sally instructions for making a small adjustment to the Shuttle’s onboard computer. It was a completely normal conversation—fairly boring to listen to—but the substance wasn’t what mattered. It was the first time that a woman on Earth had spoken to a woman in space. Mary and Sally didn’t even recognize the moment at all. They were just having a conversation. A reporter later lamented to Mary how “disappointing” the conversation was for such a special occasion.

But that was how Sally operated. For the six days that she was in space she simply did her job, trying her best to ignore any history that was being made. She couldn’t help it that STS-7 was simply bursting with historic “firsts.” Even its landing was supposed to make a statement. Their mission was slated to perform the first Shuttle landing in Florida. All previous Shuttle missions had landed at Edwards Air Force Base in California. But NASA had been working on a fancy new runway at Kennedy Space Center, and the concrete was finally ready to feel the Shuttle’s massive tires touch down.

Kathy Sullivan and Dave Leestma perform the Orbital Refueling System experiment during a spacewalk on STS-41-G.

Kathy Sullivan and Dave Leestma perform the Orbital Refueling System experiment during a spacewalk on STS-41-G.

On the day of reentry, however, that historic plan was thwarted. A thick fog bank had rolled over the landing strip, completely obscuring the landscape. Slightly bummed, the astronauts made plans to divert to Edwards. After cleaning their equipment and strapping back into their seats, Robert “Crip” L. Crippen and Frederick “Rick” H. Hauck steered the Shuttle out of orbit, sending the vehicle on its dive toward Earth. Out the window, Sally watched the bright glow of the atmospheric plasma, heating up and enveloping the Shuttle as it sliced through the thick air surrounding Earth.

For Sally, the detour turned out to be a blessing in disguise. As she walked down the stairs leading out of the crew cabin and onto solid ground, only a small crowd of air force personnel and their families were on hand to greet her and the incoming crew. She was 2,500 miles from the thousands who’d gathered at Cape Canaveral, all clamoring to see her arrive. After a quick phone call with President Reagan, who joked that the crew had forgotten to pick him up in D.C. on their way home, Sally addressed the crowd out in the California heat.

“The thing that I’ll remember most about that flight is that it was fun,” Sally told the crowd. “And in fact, I’m sure it’s the most fun I’ll ever have in my life.”

*

That fun that Sally had in orbit would soon be eclipsed by what was waiting in her new reality.

Flying home on a NASA jet, she and the rest of the crew arrived in Houston, and her husband, Steve, was there on the runway to see her. With a big smile, Sally wrapped her arms around him in a tight hug, happy to be reunited. After the rest of the crew had embraced their spouses, they all made their way to limousines that would take them to JSC for one final presentation to an adoring crowd. While at the airport, someone handed Sally a giant bouquet of white roses, adorned with an ostentatious cream bow. She wasn’t the only one to get flowers, either. All the wives of the male crewmates had each been given a red rose, though Steve hadn’t been given anything. Sally carried the massive bouquet with her until they all reached JSC.

It was then that Rosegate occurred.

A large crowd had gathered on the JSC campus, awaiting the STS-7 crew. As the five crewmates and their spouses stepped out of Building 1 to address this latest group of fans, Sally quickly turned and gave the bouquet to a NASA protocol officer. The motive was plain: she just wanted her hands free. Without the bouquet, she stood with her arm around Steve, before speaking to the crowd who cheered her on. Once the presentation was over, the officer who’d taken the flowers returned, trying to give them back. Sally, with Steve next to her, declined to take them, instead turning to talk with George Abbey.

She had no idea the controversy she just ignited.

The next day, a newspaper writer interpreted the act as some feminist statement—a way for Sally to establish equality with her male crewmates. Soon afterward, the letters began pouring in. She’d later write, “That one little action—giving back the flowers—probably touched off more mail to me than anything I ever did or said as an astronaut.”

For the six days that she was in space she simply did her job, trying her best to ignore any history that was being made.That moment was a harbinger of what was to come. All eyes were on Sally now. Back in the gravity-filled environment of Earth and without a mission to train for, she was now almost completely exposed to the adoring public who wanted to witness her every move. It began the day she came back to Houston, as crowds of neighbors and news crews gathered outside her and Steve’s home, tying yellow ribbons around the trees in her yard and holding up a banner that said, “WELCOME SALLY!”

But Sally and Steve had long planned to escape their abode that night by booking a nearby hotel room. That plan fizzled when Steve went to check in and spotted a reporter he knew hanging around. Instead, the couple went to Dan Brandenstein’s house to spend the night, leading the press to note Sally’s absence at her own home.

It was only a small glimpse at the road ahead.

In just the first month back, Sally and her fellow crew members found themselves speeding through eight different states. They traveled to New York, where they received a key to the city from Mayor Ed Koch. They attended an opulent reception at the National Air and Space Museum with five hundred attendees, plenty of whom asked for Sally’s picture and autograph. There was an intricate military ball at the Dunes Hotel & Country Club in Las Vegas. Again, Sally and the STS-7 crew found themselves at the White House, dining with President Reagan. Sally sat between Reagan and the prime minister of Bahrain, with whom she discussed the feeling of being weightless.

And the whoosh of attention showed no signs of abating. Requests were streaming into NASA to book Sally for every minuscule event. Less than a week after she returned from her flight, the agency received more than a thousand media appearance requests for her. At one point, calls into NASA’s press office asking for Sally peaked at twenty-three an hour.

With the shield of training gone, Sally’s crewmates tried to become her new shield. They made an effort to go with her to as many events as possible—to serve as a buffer between their colleague and the press. “We would minimize those appearances before the flight as much as possible,” Crip said. “And we did that. But she still had a lot of it, and after the flight, some of that protection wasn’t there.” Norm Thagard unfortunately served as a literal buffer during one press event in D.C., when hordes of TV news crews shoved him against the wall as they clamored to get the perfect shot of Sally.

Worse, the requests were starting to get bizarre, like the artist who wanted Sally to sit for a portrait created out of jellybeans. Or the production company that wanted her to act in a comedy where a child dreamt he met Sally Ride while traveling in space. As the requests continued to mount, Sally started to feel more and more out of control of her life. She was an introvert at heart, not one to seek the spotlight willingly. And here she was, seemingly meeting everyone on the planet.

One day, NASA received an invitation for Sally to visit the newly minted Sally K. Ride Elementary School located an hour north of JSC in Conroe, Texas. When Sally received word, she made it clear she did not want to go. But the school desperately wanted her, even calling the director of JSC to secure Sally’s booking. Realizing she couldn’t get out of it, she made a demand that she’d only go if Carolyn Huntoon came with her.

So the two embarked on the short road trip north, getting slightly lost along the way. Once they finally found the school, they drove up and made their way in, only to start hearing a children’s choir start singing as they walked through the front doors.

“We are proud of our school, Sally K. Ride! We will always take a challenge and always do our best…”

Panicking, Sally turned to Carolyn. “I don’t think I can do this.”

“Yes, you can, go on,” Carolyn replied. She took Sally by the arm and walked her into the school, where she was reluctantly showered with gifts and subjected to a few more verses of the school’s new song.

As the requests mounted, Sally pulled away more and more. It all came to a head when she got a request straight from NASA Headquarters’ public affairs to go on a new Bob Hope special. The popular comedian was hosting a special tribute to NASA called Bob Hope’s Salute to NASA: 25 Years of Reaching for the Stars, and some famous astronauts including Neil Armstrong had agreed to be interviewed. The production team also wanted Sally. NASA was told that this wouldn’t be a regular comedy show, but a serious discussion with Sally about her thoughts on the world and what her time was like in space. It didn’t matter. Sally turned it down.

Kathy Sullivan in her flight suit, undergoing pre-flight checks.

Kathy Sullivan in her flight suit, undergoing pre-flight checks.

Reluctant to take no for an answer, headquarters enlisted JSC director Gerry Griffin to try to persuade Sally to change her mind. He found her at work, sat her down, and asked if she’d heard about the request. She said that she had. And she wasn’t going to do it.

“Why not?” he asked.

“Because he’s a sexist,” Sally replied. Sally brought up Bob Hope’s USO tour during World War II, which involved parading women in scantily clad attire to entertain the troops. It didn’t matter that she was promised a “serious” show—she didn’t like this man’s reputation.

Gerry continued pressing but Sally stood firm. Soon after that, she just vanished.

She didn’t tell anyone where she was going, not even Steve. But that wasn’t particularly abnormal for her. She’d done this disappearing act before. Steve understood her desire to escape, though he didn’t think it was particularly responsible in these circumstances. Finally, after a week of absence, she called Steve to tell him she was okay and that she had skipped off to California, as he had suspected. She’d taken refuge with Molly Tyson and Molly’s partner in Menlo Park, making sure that an appearance on the Bob Hope special wouldn’t be imposed on her.

It was beginning to dawn on Sally that she needed some help. All her life she’d been a happy individual, excited to wake up and start each day. Now, she realized she wasn’t that same happy person. She woke up nervous, filled with anxiety about what each day might bring.

“Swarms of people surrounding her and people wanting to touch her, take her photograph, invite her to things—she slowly realized it was really getting to her,” Tam said.

In a moment of clarity, she turned to therapy. It’s unclear who exactly she spoke with, though Steve heard later that she supposedly talked to Terry McGuire, the good cop psychiatrist whom they’d all met during the selection process. Either way, Sally knew she needed an empathetic listener who could help her through this unusual time.

For the most part, Sally viewed her press odyssey as a nightmare. But scattered amid the dizzying array of speeches and networking events, there were special moments she came to cherish. She made multiple appearances on Sesame Street, where she loved meeting with the science-curious children. They asked the fun questions, such as what it was like to go to the bathroom in space. And of course, she got to meet some of the people she most idolized. Through her fame, she met Betty Friedan and reconnected with Billie Jean King, whom she’d hit balls with as a young tennis player.

But perhaps the most intriguing person Sally met was one she hadn’t expected to ever meet. At a reception in Hungary where Sally and Steve were attending a meeting of the International Astronautical Federation, Sally felt a tap on her elbow. She turned to find Svetlana Savitskaya, the cosmonaut who’d become the second Soviet woman to fly to space in 1982.

“Sally,” Svetlana acknowledged.

“Hello,” Sally said, cautious.

“Congratulations on your flight.”

“Congratulations to you, too,” Sally replied.

Their conversation didn’t last long—relations between the US and the Soviet Union had been exceedingly chilly in prior months— but later that day Sally heard Svetlana talk and decided she was a genuinely good person. Somewhat surreptitiously, Sally contrived to arrange a more confidential meeting.

Sally started to feel more and more out of control of her life. She was an introvert at heart, not one to seek the spotlight willingly.Using as an intermediary a Hungarian physicist she knew, she expressed an interest in meeting Svetlana again. Thanks to some behind-the-scenes machinations, Sally wound up being invited to meet a small group of Soviet cosmonauts at the apartment of Hungarian cosmonaut Bertalan Farkas. Steve disapproved of the meetup, conscious of NASA’s dim view of American astronauts mingling with Soviet cosmonauts, so he hung back at a coffee shop. Sally, though, was determined.

The mood at first was tense, with neither party knowing quite how to comport themselves. Sally tried smiling to put everyone at ease. The cosmonauts immediately made a joke about “no press,” which eased everyone’s anxieties. Svetlana then walked over to Sally and sat in a big armchair, right next to hers.

From that moment, the women instantly connected. Svetlana peppered Sally with questions, asking her how long she’d trained and about her flying experience. They swapped stories about the respective spacecraft they flew, with Svetlana fascinated by how the Space Shuttle landed on a runway. At one point, they all devolved into laughter about how they slept in space, with one of the cosmonauts demonstrating by floating his arms into the air.

As they spoke, Sally found that she really enjoyed talking with Svetlana. “I felt closer to her than I felt to anyone in a very long time,” she said. “And it was partly just that I understood a lot of what she had been through.”

Sally thought to herself that Svetlana would have easily made the astronaut corps in the US. In fact, she might have even beaten Sally in the race to be the first American woman to orbit if the two had been pitted against each other, she thought. Ultimately, Sally saw a lot of similarities between her and Svetlana, thinking that the cosmonaut reminded her of her colleague Shannon Lucid most of all.

Sally enjoyed her time at the gathering so much that she stayed for six hours. Long after midnight, she and Svetlana exchanged a few final words and hugged goodbye before their staggered departures.

“I left with the feeling that we would probably meet again,” Sally said. “And if we did, we would be just as close as we were at that moment.”

The whirlwind press tour had brought unbelievable highs and remarkable lows. In the middle of it all, Sally sat down with Gloria Steinem, agreeing to an interview to talk about the surreal few months she’d been experiencing. Sally discussed all aspects of her flight, placing particular emphasis on the SPAS-01 demonstration and the pictures they were able to take while in space.

“That’s probably what our flight will be remembered for, I think, is those pictures,” Sally said.

“Want to bet?” Gloria replied.

Featured image: Sally Ride and Anna Fisher work together at Kennedy Space Center on the payloads for Sally’s flight, STS-7. Anna, who was the lead Cape Crusader for STS-7, is pregnant with her first daughter, Kristin.

__________________________________

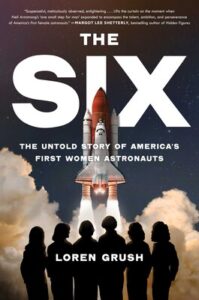

Excerpted from The Six: The Untold Story of America’s First Women Astronauts by Loren Grush. Copyright © 2023. Available from Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster.