On August 18, 2017, President Trump fired Steve Bannon, his chief strategist and, unknown to almost everyone, the guy who had given Michael Wolff access to the West Wing in order to write his book, Fire and Fury, which we bought more than a year before. We all agreed that the president firing the man most responsible for getting him the job would be a good way to end the book. Michael left the West Wing as quietly as he had come. Over the next few months, he wrote ceaselessly, crafting two hundred days of chaos into a book.

As Michael wrote, Macmillan lawyers and external lawyers carefully read every word. We were not worried about President Trump. The president of the United States controls the world’s largest bully pulpit, and the press is allowed to say what they please about him or her. But there were lots of other characters in this story, and the book had to be accurate to be credible.

When Michael finished the manuscript, we put him through days of legal review. He had a surprising number of his sources on tape, and as the meetings wore on, we became confident that even the most outlandish stories were either factual or were being reported as rumors. We asked Michael to drop several stories that did not have enough sourcing or were factually questionable.[1]

The lawyers signed off. Cloaked in secrecy, Fire and Fury, its title taken from a presidential tweet about North Korea, went to press. We placed it under embargo; no one was allowed to read it. Indeed, no one was allowed to see it. Booksellers were skeptical. We twisted every arm we could and managed to ship a relatively modest 90,000 copies.

Moving the publishing date forward was, in effect, giving the middle finger to the president.We arranged for the Washington Post to run a story on January 6, the weekend before the book published. The Today Show would run two segments with Michael on Monday, January 8, and New York magazine would run an excerpt of the book on the pub date, January 9, 2018. The books would go on sale at the stroke of midnight. None of that happened.

*

On January 2, The Guardian got a copy of the book and reported on some of the content. The press embargo was broken; New York magazine followed with their excerpts and the Washington Post with their story. Sara Huckabee Sanders trashed the book in her White House press briefing. To our great surprise, the White House released an official statement; we had been hoping for a tweet or two. The New York Times, CNN, and the Washington Post broke the embargo, and then everyone followed. The book went from #40,000 on Amazon to #1. At Henry Holt, we received forty-five press calls in less than an hour. The messenger delivering a copy of the book to the Associated Press got lost and was physically chased down on the street by an AP staffer. We began negotiations with NBC for the first interview with Michael Wolff. All of this happened in four hours.

I had to give a speech the next day at our higher education sales meeting, so while everyone scrambled to react to the frenzy, I caught a flight to Arizona. Early the next morning I was alone in the gym on an elliptical trainer, earbuds in, music cranked up, the desert dark outside the windows. Someone came in and turned on the video screens that were scattered around the place, all on different channels. On every screen, there was Michael, or failing that, the book jacket. For two minutes my head was on a swivel; Fire and Fury was clearly the lead story on every channel. I needed a phone, and I needed one quick. I jogged back to room 6503, sat at the desk, and dialed work. One after another my calls went unanswered. Finally, after dialing executives at random, I reached someone who cheerfully reported that everyone was in Don’s office, and would I like to interrupt them? I suggested that might be a good idea, and I was transferred into the meeting. Don asked if I was sitting down. Yes, I was. He reported that Donald J. Trump, the president of the United States, had just delivered a cease-and-desist letter to Michael Wolff and Henry Holt. I admit my first thought was an elated Holy shit, we are gonna sell a ton of books. Then I realized this went far beyond selling books, and my elation waned. A sitting president was attempting to subvert the First Amendment, and freedom of the press was usually the first freedom suspended by authoritarian regimes. The cease-and-desist was no small thing.

Trump’s Hollywood lawyer, Charles Harder, promptly leaked the cease-and-desist letter to the press. The phones lit up. We immediately started work on a short statement saying we would go forward with the publication. Now we had to decide if we should hold the books until Tuesday as scheduled or move up the publication date. At this point we were already shipping books to stores; some booksellers would have them, and some wouldn’t. The decision to move a publishing date forward is highly complex; it gives some accounts an advantage and it pisses everyone else off. And it is hard to stop those who do have the book from selling it. Most importantly, we knew we would send a message if we moved the pub date forward. Still in Arizona, I took the easy way out and left the decision to Don, whom I trusted completely. Don made a bold choice. On Thursday morning we announced in response to the president’s letter that we would move the release date up to the next day, Friday. Every account was called, more books were ordered, shipping companies were pushed, media outlets were informed, and publicity schedules were adjusted. All hands on deck. A prominent blogger posted that moving the publishing date forward was, in effect, giving the middle finger to the president.

The phones in the sales department were ringing off the hook. Every account wanted more books, lots and lots more. There was not enough capacity at the printers, nor paper at the mills. There was a shortage of truck drivers. There was a bomb cyclone on the East Coast that closed the UPS hub in Toronto. Who had even heard of a bomb cyclone?

At my talk in Phoenix, I asked the gathered employees and authors if they wanted to hear my speech, or would they prefer to hear what it was like to be me on that particular morning. The one-sided response made it clear that everyone had already heard the news. I stayed for an hour, mostly answering questions, before hurrying back to room 6503 and the phone.

I got late checkout.

The greatest concern was getting books. We dealt with three big printers and two paper suppliers at the time. I wrote to the five CEOs and explained that we could not run out of this book now, not when the president was trying to suppress it. I asked them to work together, instead of competing, to quickly get us as many books as possible. The response was immediate and gratifying. Richard Garneau, the owner of Resolute Paper, a Canadian company and our largest paper supplier, wrote a note to all his plant managers: “You guys get Macmillan all the paper they need: where and when they need it. No excuses, make it happen.” It didn’t hurt that the president had recently started talking about tariffs on Canadian paper.

Trump’s cease-and-desist letter demanded a response by Friday, and our lawyers were hard at work with outside counsel to get that done. I intervened and suggested that we break with standard protocol, ignore their timing request, and hold our answer until Monday. We would have one shot at this; we should make the most of it. To that end, I called Chris Finan at the National Coalition Against Censorship. I would be writing our public response, and my knowledge of First Amendment legal cases was limited. I asked Chris, a First Amendment scholar, for all the relevant Supreme Court decisions, and in particular the relevant language in the majority opinions. The justices are generally eloquent, and I hoped to use their words. Chris committed to getting me results in a day, and he and his staff got to work. I flew home, spending my entire time in the airport walking, a phone stuck to my ear.

The next morning Michael went on the Today Show. The book went on sale and promptly sold out everywhere. The president, aiding our cause, started tweeting. That afternoon, Chris, true to his word, delivered a stack of Supreme Court decisions. Across Macmillan, people focused on the complex logistics needed to get books delivered and more books printed. We dropped the special effects on the cover, changed the board material, and swapped out the hard-to-get paper. We used extra printers, including a printer in Germany to print the English language export edition for Europe.

On Friday night I sat down and thought about what we should do on Monday. I knew our outside lawyer, Elizabeth McNamara, was working on an extremely aggressive legal response. But I also knew we had to get out an explanation of what the president was trying to do and how very wrong it was. It would be difficult to address in a press release. I also knew that many of the people in our company did not fully understand the complexities of libel, the First Amendment, and how they fit together. It dawned on me that I could write a letter to our employees and release it to the press. Two birds, one stone.

I worked at home most of Saturday on a short note. Various people at Macmillan helped. The most difficult thing to convey was that Trump’s letter wasn’t a court filing or a lawsuit, and thus wasn’t under court jurisdiction. Paul Sleven, our general counsel, finally figured out the right language: “We will not allow any president to achieve through intimidation what our Constitution precludes him from achieving in court.” I added “or her” after “him.” I finished the letter just after 5:00. I was particularly proud of the last line: “Mr. President, go fish.” I thought it perfect, capturing the very essence of the matter. Connie pointed out that it might be more sophomoric than brilliant. I reluctantly changed it, and the last line is better for Connie’s intervention.

Message from John Sargent: Fire and Fury

Last Thursday, shortly after 7:00 a.m., we received a demand from the President of the United States to “immediately cease and desist from any further publication, release or dissemination” of Michael Wolff’s Fire and Fury. On Thursday afternoon we responded with a short statement saying we would publish the book, and we moved the pub date forward to the next day. Later today, we will send our legal response to President Trump.

Our response is firm, as it has to be. I am writing you today to explain why this is a matter of great importance. It is about much more than Fire and Fury.

The president is free to call news “fake” and to blast the media. That goes against convention, but it is not unconstitutional. But a demand to cease and desist publication—a clear effort by the president of the United States to intimidate a publisher into halting publication of an important book on the workings of the government—is an attempt to achieve what is called prior restraint. That is something no American court would order as it is flagrantly unconstitutional.

This is very clearly defined in Supreme Court law, most prominently in the Pentagon Papers case. As Justice Hugo Black explained in his concurrence:

Both the history and language of the First Amendment support the view that the press must be left free to publish news, whatever the source, without censorship, injunctions, or prior restraints. In the First Amendment, the Founding Fathers gave the free press the protection it must have to fulfill its essential role in our democracy. The press was to serve the governed, not the governors. The Government’s power to censor the press was abolished so that the press would remain forever free to censure the Government.

Then there is Justice William Brennan’s opinion in The New York Times Co. v. Sullivan:

Thus we consider this case against the background of a profound national commitment to the principle that debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust and wide open, and that it may well include vehement, caustic, and sometimes unpleasantly sharp attacks on government and public officials.

And finally Chief Justice Warren Burger in another landmark case:

The thread running through all these cases is that prior restraints on speech and publication are the most serious and least tolerable infringement on First Amendment rights.

There is no ambiguity here. This is an underlying principle of our democracy. We cannot stand silent. We will not allow any president to achieve by intimidation what our Constitution precludes him or her from achieving in court. We need to respond strongly for Michael Wolff and his book, but also for all authors and all their books, now and in the future. And as citizens we must demand that President Trump understand and abide by the First Amendment of our Constitution.

—John

While we were working on the note, the president spent the day tweeting. Speaking of himself, he claimed, “the two greatest assets have been mental stability and being, like, really smart.” He went on to define himself as “a very stable genius.”

A cultural moment is hard to define, but a Saturday Night Live opening skit is a good marker.Sunday seemed calm, but unnoticed by any of us at the time, WikiLeaks posted the full text of Fire and Fury. They had found an unprotected PDF of the book that had been accidentally sent in an email by the British publisher. Over the next week WikiLeaks would push out free copies with a marketing campaign.

Monday arrived; it was time to respond to the president. We sent out the letter to our employees, and then leaked it to the press. I lost control of my inbox. Our outside attorney sent President Trump’s lawyer our legal response. At the beginning she said, “As a result, you demand that my clients cease publication of the book and ‘issue a full and complete retraction and apology.’ My clients do not intend to cease publication, no such retraction will occur, and no apology is warranted.” And at the end she said, “Lastly, the majority of your letter—indeed seven full pages—is devoted to instructing Henry Holt and Mr. Wolff in meticulous detail about their obligation to preserve documents…At the same time we must remind you that President Trump, in his personal and governmental capacity, must comply with the same legal obligations regarding himself, his family members, their businesses, the Trump campaign, and his administration, and must ensure all appropriate measures to preserve such documents are in place. This would include any and all documents pertaining to any of the matters on which the book reports.”

If nothing else, we were direct. The press coverage was enormous and global. The International Publishers Association issued a statement of support for Macmillan. That night the book reached its peak rate of sale, 23,000 copies per hour at Amazon alone. My boss called from a conference in Europe; he was delighted, everyone there was reading the book. But he reported that they were reading it on their devices, for free. The WikiLeaks post was becoming a serious problem.

I had spent years helping negotiate an industry agreement with the guys at Google, and we had become friendly. I called them now and asked for their help. They agreed to make the takedown of the illegal edition of Fire and Fury their top priority globally. At Macmillan, we assigned two people to scan the web on a continuous basis looking for infringing copies. Normally it takes several days to take down a copyright violation, but Google was now getting it done in seconds.

By Tuesday, the original publication date for Fire and Fury, we had ordered 1.5 million books in twenty-two printings at five different printers, including the one in Germany. All of the books would be delivered within a week. For the German-language edition, we had hired seven translators to get the book out as quickly as possible. In the short gap before the German-language edition became available, the English-language version was the #1 selling book in Germany.

Fire and Fury, and Michael, dominated the news cycle for several weeks. A cultural moment is hard to define, but a Saturday Night Live opening skit is a good marker. It almost never happens for a book, but with Bill Murray playing Steve Bannon, it happened for this one.

Several weeks later, I gave my annual year-end speech to all our New York employees. I talked about the book and what it meant, to me and to our company. I asked Steve Rubin, who bought the book and published it, to stand up. There were cheers, of course. Then I asked John Sterling, the editor of the book, to stand. And then Maggie Richards and Pat Eiseman, who handled the marketing and publicity. Then I asked everyone at Henry Holt who worked on the book in any way to stand. Then everyone involved with the supply chain and printing the book, stand up. Alison Lazarus, our head of sales, and everyone who sold books to our accounts, stand up. By then there were more than six hundred people on their feet. I talked about the warehouse in Virginia that carried the load and our cousins in Germany. I called out twenty-six people throughout the company by name, ending with Don, who had tirelessly guided our efforts from beginning to end. And then I asked everyone who had told people about the book, and thus spread the word, to stand. Some folks may have still been in their seats at that point, but I couldn’t see them. I asked everyone to give themselves a big hand. They all deserved the standing ovation.

[1] After the book came out, many of the people mentioned threatened to sue us, but in the end, nobody did. The truth is the best defense against libel claims.

_________________________

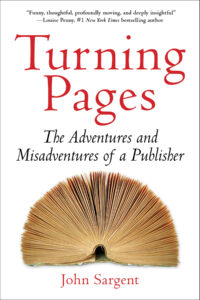

From Turning Pages: The Adventures and Misadventures of a Publisher by John Sargent. Copyright © 2023. Used with permission by the publisher, Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.