Finding Good Advice in World War II-Era Women’s Magazines

"The advice isn’t always consistent, it’s not always pleasant, but it is always fascinating."

I first came across a copy of a 1939 British women’s magazine during an enthusiastic bout of procrastinating on eBay. Expecting nothing more than a mildly interesting read for my £4.95, a few days later, I found myself beginning what became a collection of hundreds of vintage magazines, a Sunday Times bestselling debut novel, and a new career as a novelist. As you can imagine, I’m still a keen supporter of timewasting online.

That’s a pretty exciting series of events instigated by a magazine featuring a cheery woman wearing a sun hat on the cover, with the headline Knit This Beach Suit! But perhaps that’s the whole point. What on face value looked like a fun read became (as did countless other magazines in this genre) a source of some of the most interesting, significant, and inspiring material I’ve used in my research.

That copy of Woman’s Own was an accessible, relatable glimpse into the lives of women in 1939. The pages were filled with fashion, beauty, fiction and films, a recipe for salmon in a sauce and a set of stomach exercises, adverts for Band-aids, Tampax, and McDougall’s self-raising flour. It was a magazine for me—if I had been getting on with life over eighty years ago.

1939 is the year Britain went to war with Germany. The magazine I was holding would have been read just weeks before war was declared. It gave me an entirely new doorway into that world and, for the first time, made me think about writing historical fiction.

If you’re wondering if salmon in a sauce is a little bit shallow as a gateway for a novelist, stick with me. Two columns in particular stood out. The first was called What Women Are Doing and Saying which featured news of a group of female boat builders—the eldest only eighteen—who had been taught by their father “because boy apprentices found work too tough (and) would not stay.” Then it told readers about Dr. Gisa Kaminer, the Austrian scientist assisting Professor Ernst Freund as he set up his London cancer research lab, having been exiled by the Nazis. The women had serious stories to tell.

The final feature, and the one that became the basis of my series The Emmy Lake Chronicles, was the advice column at the back. I was surprised at how many of the readers’ problems still had resonance. From the mother concerned that her daughter wasn’t working hard enough at school, to the twenty-year-old whose parents said she shouldn’t get married, to the woman whose husband was seeing way too much of a young married woman, they didn’t feel like history. They felt as if they could have been written today.

My £4.95 had bought me a time machine.

In the ten or so years since then, I’ve built a magazine collection that ranges from the 1960s back to a volume of The Lady’s Magazine: Or Polite Companion For The Fair Sex from 1761, including, for fans of Bridgerton’s Queen Charlotte, a report on her wedding to King George (it was not a small do). The majority of my collection, however, is from World War II, when the almost unimaginable challenges of war added layers of stories to the previously relatable advice. Nothing beats first-hand accounts of course, but in terms of understanding what mass numbers of women were concerned with and reading about in their everyday lives—these publications have been invaluable.

While the bulk of the magazines tells me what women ate and drank and wore, or the brands they bought or the radio programs they listened to, it’s the advice columns that reveal the issues that really mattered to them: those concerns that kept them awake at night to the extent they were would write to a complete stranger and ask for help.

This is gold to a writer.

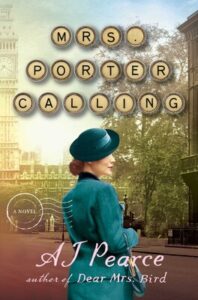

Equally, it is the responses of the advice columnists which give serious insight into the views, morals, and judgements of the period. In general, I have found them to be highly supportive of their readers, but I would be remiss not to say that the attitudes are very much of their time. Supportive on some issues, while on others revealing horrible bigotry. It’s not always comfortable reading, but it’s an insight I use in my work. In my debut novel, Dear Mrs. Bird, a young reader writes that she is in love with a Polish airman, much to the disapproval of her parents. The elderly advice columnist in the novel makes it clear that while the young man’s service in the war is much respected, marrying someone “from overseas” is not. It gave me the conflict I needed for the book’s young, far more modern protagonist Emmy Lake. In my most recent novel Mrs. Porter Calling, Emmy is now an advice columnist herself, and fights for her readers on every page.

I was especially fascinated by the role of advice columnists in the war effort. Women’s magazines played a key part in the British Government’s communications. The Ministry of Information worked with the women’s press to reach millions of readers needed to join the war effort: recruiting to the services and factories, and crucially, maintaining the home lives and families that everyone was fighting for. If the cookery pages moved into making rations last and promoting carrots when the Ministry of Food predicted a glut, it was the advice columnists who had to deal with the emotional as well as practical impact of years of conflict. The readers’ problems in my novels are almost all based on letters published in original magazines. In just one issue, a wartime advice columnist might tackle loneliness, loss, grief, unplanned pregnancies or sexually transmitted diseases as well as the “usual” problems of mothers or daughters or work or money.

The columnists are supporting their readers, championing them, informing, warning and in some instances, judging. Depending on the magazine, the advice isn’t always consistent, it’s not always pleasant, but it is always fascinating.

It’s also increasingly hard to find. If you spot a stack of old magazines in your attic, please don’t throw them away. Even better, let me know about them. They hold so many stories I still want to tell.

__________________________________

Mrs. Porter Calling by AJ Pearce is available from Scribner, an imprint of Simon and Schuster.