It’s difficult to choose my favorite Norman Mailer fight. There was the time he head-butted Gore Vidal in the green room of The Dick Cavett Show and then—swaggering on stage truculent with drink—got himself verbally mauled by Vidal, Cavett, Janet Flanner, and a hooting studio audience (video below). Or maybe my favorite Mailer fight was his 100 percent vérité tussle with Rip Torn in his experimental film Maidstone (capsule play-by-play: Torn taps Mailer twice on the head with a hammer; Mailer tries to bite off Torn’s ear; they go to the ground; getting the worst of it, Mailer negotiates a fake truce; Torn relents, Mailer attacks; again getting the worst of it, Mailer is saved by his ferocious wife; Torn and Mailer exchange verbal haymakers; Mailer whiffs; Torn lands). Or there was the time Mailer drunkenly fought—or tried to fight—nearly every man he invited to a party, arguing with many and stepping outside at least three times to throw dukes on the sidewalk. Later that same night he stabbed his wife twice with a pen knife after she called him a “little faggot” with no cojones (not one of my favorite Mailer fights; she almost died).

This is going to take too long. Suffice it to say that, going by J. Michael Lennon’s biography, Norman Mailer: A Double Life, Mailer seems to have mixed it up—verbally or physically, playfully or in dead earnest—with most of the men he ever met. The book alludes to around 20 punch-ups, the last of which occurred when, at 74, he slugged the publisher of Esquire over a review he didn’t like. Of all the tiffs, tussles, and donnybrooks described in Lennon’s biography maybe this is my actual favorite. Imagine it: Mailer is living in small-town Connecticut. He takes his dogs out after midnight to relieve themselves. He chances to stroll past a few young men sitting on a porch, one of whom points out the obvious: Mailer’s well-groomed poodles were probably queer. Mailer must have seen the implication: Who would own homosexual dogs, if not a homosexual man? In the middle of the night, with no one there to impress, one of the world’s most famous authors demanded satisfaction. Mailer well knew how to fight dirty, but the young man better. When Mailer kept coming after getting one eye gouged, the young man gouged the other, and then a second man stepped in and sucker-punched him. Fearing for his life and bleeding from both eyes, Mailer surrendered and dragged himself home. Laid up in a dark room for days afterwards, he didn’t feel too badly about himself: there was only dishonor in flinching from a fight, not in losing decently.

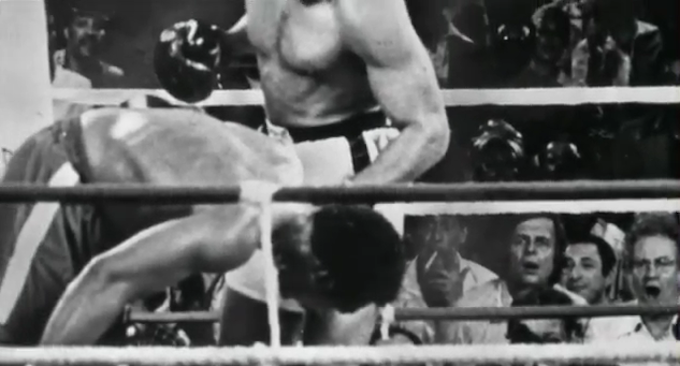

Norman Mailer wasn’t always playing the violent maniac. But his pugnacious nature shone in all he did, even his choice of leisure. Boxing was one of his great sustaining joys. He liked to watch boxing; to hang out with boxers; to think and write about boxing. And he loved to box himself—with friends, family, and various pro boxers who he befriended over the years. The pros credited Mailer with a predictably aggressive, straight-ahead style, and a mean left hook. Mailer had a ring built in his barn, and he sparred in it, and at a city gym, until he was 60. In 1971, Mailer even went on The Dick Cavett Show to pull a stunt reminiscent of George Plimpton’s 1959 tilt with Archie Moore. Mailer sparred three televised rounds against his friend, former champion Jose Torres, in order to help Torres promote a new book and, one suspects, to demonstrate that he was a two-fisted warrior-scribe—not one of your literary Nancy boys.

Four years ago I took up fighting almost by accident. I was finishing up my first decade as an adjunct instructor of English, and I was facing the ruin of my career. I’d run hard in the academic race, I’d published well and received some notice for it, but the tenure track just hadn’t opened for me—and it wasn’t going to. I was almost 40 years old. What would I do with the rest of my life? One day, pacing from my adjunct’s cubicle to the adjoining lounge, I glanced out the front window and saw that a new business had moved into the building across the street. It was called Mark Shrader’s Academy of Mixed Martial Arts—you know, the thing where they lock two guys in a chain-link cage, and see who can fight his way out? Peeping through the English Department windows I could see the fighters sparring in the cage—dancing, hitting, tackling, rolling. And I felt a great sense of envy for those young men who were so alive in their cage, while I was rotting in my cubicle.

I decided that I would join them. I’d never been in a fight before. I’d never punched a man with sincerity. I’d never stood up to a bully and absorbed a decent beating just for the principal of it. In truth, I wasn’t sure if I’d ever done a brave thing. Moving from the English Department to the fighting cage, I didn’t allow myself, as I might have when I was younger, any Bruce Lee fantasies of martial prowess. I knew I was too old and too craven to ever excel at violence. Really, I just wanted to get in the cage and take my swings. And when I got knocked down, I wanted to see if I had it in me to stand again. I wanted to know if it was possible for a man who is not brave to practice being brave until it became habitual.

And I had another motive. I wasn’t sure what I would do with the rest of my life, but I’d begin by crossing the street to gather experience for a new book. I wanted to ask—once again, in my own way—what has to be the great question of history: Why do men fight? It’s obvious why violence is so repulsive. But why can it also be so alluring?

Plimpton and Mailer, briefly at a loss for words.

Plimpton and Mailer, briefly at a loss for words.

When I first crossed from the English Department to the fighting academy, I didn’t know that I was enacting a kind of literary cliché. Of course, I knew that guys like Hemingway, Mailer, and Bukowski cultivated tough reputations, but I didn’t know that so many of the writers I admired were also attracted to fighting sport. There are the usual suspects, of course. Jack London loved to box and was the first to cry out for a “great white hope” to beat the negro champion Jack Johnson. Ernest Hemingway was a famously keen connoisseur of the fistic arts as well as an enthusiastic recreational pugilist. Other notable writers who took a strong interest in boxing, either as spectators or participants, included Lord Byron (who trained avidly with former heavyweight champion John “Gentleman” Jackson), John Keats (who was said to be dead game in a street fight), Albert Camus, A. J. Liebling, Richard Wright, D. H. Lawrence, Vladimir Nabokov, William Hazlitt, Robert Graves, William Thackeray, F. X. Toole, and of course George Plimpton (who wheeled gracefully in the ring and boasted a long, educated jab). This is a predictably manly list. But women have made lasting contributions to fight writing, including the unlikely aficionado Joyce Carol Oates, whose On Boxing is the single most indispensable study of the subject. [Ed.’s note: Katherine Dunn stepped into the ring on many occasions, and wrote about it, too.]

The writers on this list gravitated to fighting for much the same reason I did. Those who entered the ring, went there to get the weakness and timidity pounded out of them and to exercise masculine capacities that would otherwise waste away in the course of a soft literary life. Those who simply watched from the stands were drawn partly by the impossible-not-to-watch spectacle of a fist fight and—as unlikely as it may at first seem—by a strong sense of kinship between the arts of writing and fighting. “An absolutely necessary part of a writer’s equipment,” wrote the novelist Irwin Shaw, “almost as necessary as talent, is the ability to stand up under punishment, both the punishment the world hands out and the punishment he inflicts upon himself.” A great boxer, like a great writer, surpasses mere mortals not just in talent, but in work ethic, pain tolerance, and the genetic advantage of a “good” knockout-resistant chin. The arts of fighting and writing require constant editing of style—with practitioners adding on here, razoring there—restlessly seeking grace. And boxers and writers are both in the drama business. The writers saw fighting not so much as a sport, but as a genre of tragic theater, with brave actors improvising on a spot-lit stage.

Or maybe this is my favorite Norman Mailer fight. It’s 1971 and Mailer is up on stage all round and rumpled and messily Jewfro’d. He is standing alone in debate against a dais full of formidable feminist writers, and a large crowd of women’s liberationists who have come to see Mailer ritually slaughtered for his crimes against the movement. In a life that was like one great battle, this was one of Mailer’s most spirited and somehow charming performances. He was coarse in his usual way, offering to whip out his “modest Jewish dick” for the women to laugh at and spit on, and calling out to a heckler, “I mean, fuck you! I’m not gonna sit here and listen to you harridans harangue me and say, ‘Yes’m, yes’m.’” But mainly he was coarse in the winkingly flirtatious manner of the pro-wrestling heel, using rope-a-dope tactics to work the women into an amused fury, and ultimately battling them all to a breathless and exhilarating draw. The feminist writer Germaine Greer shared the stage with Mailer, and more than matched his pugnacity and brilliance. In her prepared remarks, Greer delivered a famous critique of “the masculine artist,” and implicitly of Mailer himself. “Perhaps what we accept as a creative artist in our society,” said Greer, “is more a killer than a creator, aiming his ego ahead of lesser talents, drawing the focus of all eyes to his achievements” leaving his path “strewn with the husks of people worn out and dried out by his ego.” Mailer disputed nearly everything the women said that night, but not this. He called Greer’s sentiments “exquisite.”

Earlier I spoke of crossing over from the English Department to the fight club across the street. But of course an English Department is a fight club—it’s just one where licks are given with words not fists. When you get a PhD in English, you are getting a degree in combative arts. You are learning to use tools of scholarship—and the sweet science of rhetoric—to prevail in the battle of ideas. Professorial life may seem quiet and sedate from the outside, but it is fiercely competitive, with smart people driving for as much as they can get. Currently, the path of every English PhD who fights through to tenure is strewn with the dried husks of three failed competitors.

The literary world also seems ultra-civilized from the outside but, for Greer, it was dominated by a type of man for whom “battle is dearer… than the peace could ever be.” Maybe Greer overstated her case, but with so much authorial talent battling for such a sharply limited supply of book contracts, readers, prizes, and dollars, getting to the top of the heap takes competitive drive as well as talent. The delicious stories of authorial fisticuffs—Mailer punching Vidal at a cocktail party some years after the head-butting incident (laid-out on the floor, Vidal is said to have quipped, “Words fail Norman Mailer once again!”); Hemingway beating the tar out of Wallace Stevens on the streets of Key West for slagging him; Theodore Dreiser slapping Sinclair Lewis around over the latter’s accusation of plagiarism; William Buckley thrusting out his cartoon jaw and threatening to gay bash Gore Vidal on live TV (“Now listen, you queer, stop calling me a crypto-Nazi, or I’ll sock you in the goddamn face and you’ll stay plastered!”)—are just rare escalations of a quietly fierce contest that’s constantly ongoing in the publishers’ offices, in the literary reviews, and in the salons of Manhattan.

The arts of fighting and writing require constant editing of style—with practitioners adding on here, razoring there—restlessly seeking grace.

“Which writer would you most like to fight?” You might be surprised how often I’ve been asked this question by friends and colleagues. Most of us can only imagine punching another person—really punching them—in a situation of extreme duress. We’d have to be deranged with anger or fearfully defending our lives. So they are really asking, “Which writer do you hate the most?” And I always name some wretch of a book critic who dug under my skin, and who would benefit from a fistic correction. But I’m only giving a joke of an answer to a joke of a question.

Here’s something I learned by sparring and fighting that I couldn’t have learned watching from the stands. In a sport fight, the violence is largely warm and comradely, with opponents trying to wound each other in a spirit of mutual respect and admiration. By the end of the fight, as the competitors shake hands and embrace, most fighters have fallen in love a little. One of the first times I engaged in heavy sparring at the gym, my opponent hit me so hard and often that he gave me a two-day ache in my brain. But when the final bell rang we embraced heartily and walked out of the cage patting each other’s backs with our mitts, and congratulating each other on this punch or that dodge. We’ve been good friends ever since. That night I wrote in my MMA journal: “It’s a paradox: Nothing makes men love each other like a good-natured fist fight.” Emotionally and physically, fighting is the second most intimate thing two men can do together. Actually, it may well be the first most intimate thing.

So I don’t care if it’s hackneyed: in my fantasies, I’m fighting Hemingway or Mailer. I want to fight them not because I hate them, but because I can’t help but love them, and I know a good fist fight might make them love me back. I don’t know who would win, nor do I much care. Hemingway was a lot bigger than me, and probably tougher. But he was no athlete, and he never fared well against real boxers. Mailer was smaller than me, rounder and softer—but he was also much, much meaner. In my fantasies, I hold my own in the ring, but when it comes to writing, I know I’m not in their weight class. So when a critic dismissed my new book on fighting as, “A personal history of violence that makes Norman Mailer look nuanced by comparison,” I barked with joy. Did the critic think I would take it hard being compared, even negatively, to one of the most incandescent writers and personalities of the modern age? I read the insult over again, fondling the comparison in my mind. More Norman Mailer than Norman Mailer? I shook my head a little sadly. I thought of Papa’s perfect ending line from The Sun Also Rises, and murmured it aloud: “‘Yes,’ I said, ‘isn’t it pretty to think so.’”

Jonathan Gottschall’s The Professor in the Cage is out now from Penguin Press.

Jonathan Gottschall

Jonathan Gottschall is a distinguished research fellow in the English Department at Washington & Jefferson College. He is the author of The Storytelling Animal, a New York Times Editor's Choice and finality for the LA Times Book Prize, and The Professor in the Cage, one of the Boston Globe's Best Books of the year. He has written for or been covered in the New York Times, Scientific American, the New Yorker, the Atlantic, the Chronicle of Higher Education, and The Millions. Gottschall has also appeared on popular podcasts like Star Talk, The Joe Rogan Experience, and Radiolab. He lives in Pennsylvania.