Feed a Fever, Starve a Cold, but What Do We Do for Cancer?

When a Cook Confronts Her Mother's Illness

Turn the oven to 500 degrees and assemble the ingredients: this will go very quickly. On the counter, the last of our winter’s store of beef, though we should know better than to save things by now. Is it for a celebration that we have saved the best for last, the filet mignon to be eaten after the last chemotherapy, to mark the moments when the neuropathy dissipates?

My father volunteers to grill the meat, but Oh, no, I say fiercely, with such a look of disdain and horror that he raises his hands in surrender and grins. Agnes will do it. My mother, resting on the couch, gives me a look that is not quite sarcasm. Some call the filet the most boring cut of meat, as it does not have the character of muscles that receive more use. These filets are at room temperature, patted dry, and then lightly oiled. Agnes is too well seasoned to allow sticking, but the trick is not to touch the steak either: in the hiss and sputter, the magic of the Maillard reaction is turning amino acids and simple sugars on the surface of the steak into hundreds of brand-new molecules that continue to break down into still further compounds. Searing is not about sealing in juices. This is not caramelizing, which is based on sugar. This transformation is something else entirely.

The steak will release itself when it is ready, which is important to remember. The steak knows more than I do. My mother remembers her mother standing in front of the stove in her slip and apron on a Sunday morning, browning a roast before they left for church. Searing is chemistry, it’s alchemy, it’s magic I don’t understand, the way I don’t understand how oil polymerizes on the surface of my skillet to turn the cast iron more nonstick than Teflon, in the way that I don’t understand how the chemical composition of my mother’s chemotherapy attacks cancer cells in her body, but also is a fertilizer to grow crops where they have not been able to grow. I wonder about that moment when the steak hits the pan, the sear, that moment where two things that cannot coexist meet—the hot and the cold, the fire and the raw—and must change into something completely different. The sear on a steak, toast in the toaster, the browning of my favorite English roasties, even the magnificent crust of the cakes I make in this skillet, the tool my mother’s doctor used to cauterize vessels during her hysterectomy, the fire to harm or heal, the flames in the gas fireplace that go nowhere, consuming and producing nothing.

After five minutes in that 500-degree oven, the filets rest on plates with their potatoes while I put the skillet back on the burner to deglaze with the dark tang of Worcestershire sauce, enjoying the hiss of it as I scrape the pan with my flat-bottomed wooden spoon, hoping I can remember the flavors of the pan sauce of my favorite steak in my favorite dark tavern in Ohio. The liquid reduces immediately, quicker than I am ready for, and I add a bit of butter and stir as it melts and hope it tastes good, because I won’t taste it. I must have faith. The grated parmesan is ready to sprinkle on the finished steak. I turn away, ready to drizzle the sauce, and, forgetting myself, I reach back for the skillet’s handle with my bare hand.

We can’t go back to the way we were. This time will always be the burn scars on my hands, the white slices of knife slips. It may not hurt anymore, but we are marked.

*

You will find bright brass bells in nearly all cancer treatment centers across the country, a small moment of ceremony to mark the transition of a cancer patient from one place into the next. Perhaps it is the end of radiation, as one transitions into chemotherapy, or perhaps it signals the end of all treatment and the return to a life where one does not have to worry about platelet counts. On the day of my mother’s last chemotherapy, she rings the bell we’ve walked by every time we visit, the brass eight inches tall, inscribed with the name of the family who donated it. The nurses and staff gather to watch my mother proudly snap the clapper, three loud, sharp tones that echo through the infusion center. They hug her, some with tears in their eyes. She smiles.

They’ll never know what it’s like to hear your doctor say cancer, to feel like you are speaking a language nobody can understand.

A man in an orange shirt comes to investigate, peering at the bell as the room returns to quiet. He introduces himself. It is his first time here. My mother listens patiently to his story, even as I hear the tone of voice that G.’s doctor used, that weirdly firm and compassionate register, because I held my mother’s hand the day her doctor told her the same. Later, my mother says, You don’t really get names in there. And you’re more likely to talk about road construction than “what are you in for?” There are Homeric epics to be written in the spaces between words in this place, in what cannot be said in response to You have cancer. What else is there to say beyond I’m so sorry—we know what awaits you.

I marvel at the intimate details G. shares with a perfect stranger, this man looking for anyone to understand that even though you may have a supportive group of family and friends, they’ll never know what it’s like to hear your doctor say cancer, to feel like you are speaking a language nobody can understand, what it feels like to have that port in your chest, to feel the hair you are losing stick to your lips, to know how cancer becomes invisible when hair grows back, when scars heal, when what has happened inside your body returns to quiet and people forget.

I picture G. in that bright orange shirt, the crew neck stretched out as if he’d been tugging on it, filling the space with his life story as my mother rings the bell. That was us, six months ago, unsure, afraid, looking for the grounding of human connection to make the transition to treatment bearable. Maybe G. will tell the story of a woman he met on his first day, a woman whose name he never caught, as she rang the bell and then walked out the door.

*

My friend J. asked me to tell him a childhood story of wind and I told him of standing on the red cinder block retaining wall next to the garage when I was eight or nine, and watching the westernmost pine tree in the yard, the branches closest to the ground so still they could balance a bubble on the needles, but the very tops of the tree were fussing, as if they knew something we didn’t. The sky was green and I could hear thunder, but where I stood was too still even to be called calm. I felt stalked, though I could not have articulated that as a child. I was in the presence of a predator. I stood motionless and watched the tree’s top, recognizing for the first time what a storm smelled like.

It’s hot today, the heat index over one hundred, and we close the house against it, the curtains, even ourselves, as if quiet will cause the heat to pass by unnoticed, the way I remember childhood days before air conditioning, closing the east side of the house in the morning and the west side in the afternoon. In the hungry quiet of this June morning, I don’t know what to do now that my mother’s chemo is over, the CT scans clear of cancer, but the absence still feels wrong, somehow. I am suspicious of this calm, as I will be every three months as we wait for the results of her CT scans, waiting for the storm I know must lurk beyond the stillness. I struggle against this frozen moment that still feels like waiting, the expectation that we will carry on as if the last six months never happened, the release of the tension so abrupt as to be disorienting. We have held tight for so long.

Anyone who’s been through an illness like cancer knows there’s a point where everything contracts, pulls in like blood to the core, away from the limbs, into the empty space in my mother’s abdomen where her uterus with its three-pound embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma tumor used to be. Language becomes predatory. Fingers become superfluous, the need for circulation to the knees, gone. The body becomes a fist. This is how we survive: We don’t struggle. We still. My mother has no detectable cancer, but we still worry about those cancer seeds, waiting in the stillness to replant themselves.

![]()

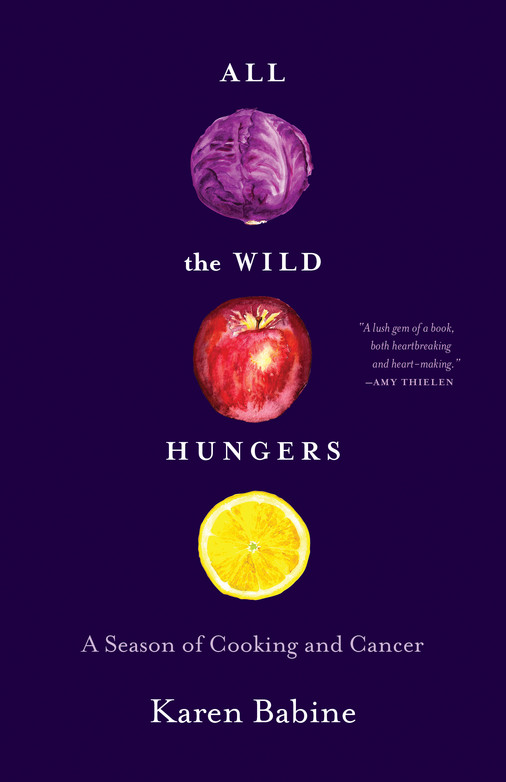

From All the Wild Hungers, by Karen Babine, courtesy Milkweed Editions. Copyright 2019, Karen Babine.

Karen Babine

Karen Babine is the author of All the Wild Hungers: A Season of Cooking and Cancer (Milkweed Editions, 2019) and Water and What We Know: Following the Roots of a Northern Life (University of Minnesota, 2015), both winners of the Minnesota Book Award for memoir/creative nonfiction. She also edits Assay: A Journal of Nonfiction Studies. Her work has appeared in such journals as Brevity, River Teeth, North American Review, Slag Glass City, Sweet. She is an assistant professor of creative writing at the University of Tennessee-Chattanooga. Find her on Twitter , Instagram, and online at www.karenbabine.com.