Fear and Loathing in New England: Lev Grossman Looks Back at His First Novel

"I wasn’t really a slacker; I was more just a loser."

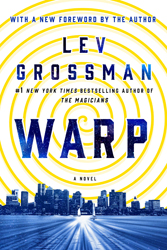

I wrote my first novel over a period of about five years, 1992 to 1996, in a series of increasingly tiny, dingy, cheap apartments full of roaches and non-right angles and off-brand miniature kitchen appliances, first in and around Boston, then in New Haven, and then in New York City.

I remember each of these apartments in encyclopedic and totally unnecessary detail. A dark-wood studio, perfectly cubical, in an old building that still had a cage elevator; the second floor of a listing clapboard house where I stuffed pillows into the heating vents to try to muffle the neighbor’s TV, and which contained the last non-ironic black-and-white TV I ever watched; a cell in a hospital that had been repurposed as dystopian graduate student housing.

In each of these apartments I wrote and rewrote and rewrote Warp, working at a desk made of an old door propped up on two trestles, using a chunky beige Mac Classic with a tiny monochrome screen like an oscilloscope. Five years is a long time to spend on a novel as short as this one, but I wasn’t messing around. I worked on Warp constantly, whenever I could, usually every day, jobs and classes permitting. It is the intense, concentrated, boiled-down essence of the unhappiest years of my life.

The low point may have been my stint as a liquor store accessories salesman—you know, novelty bottle-openers and such—from which I was fired after one day.

When I left college in 1991, I was profoundly unprepared for the demands of everyday life, emotionally, professionally, financially, and in every other possible way. For years I couldn’t seem to get a career started. I worked dead-end internships and temp jobs—as I wasn’t presentable enough to answer phones, the temp agencies generally sent me out to do word processing in Dunder Mifflin-style offices and “light industrial” tasks in warehouses. The low point may have been my stint as a liquor store accessories salesman—you know, novelty bottle-openers and such—from which I was fired after one day. I read Roger Zelazny novels, drank cheap vodka, listened to WFNX, wrote scores of bad short stories, and played Beyond Dark Castle II on my Mac Classic. When I wasn’t working, I went to bed at dawn and woke up at noon.

These were lonely, depressing years. Like Milo in The Phantom Tollbooth, I was stuck in the Doldrums. I had few friends, and my isolation and lack of success made me bitter and self-involved, which led to my having even fewer friends. (This was before the mass adoption of the Internet and cell phones, remember, when isolation had real teeth: no email, no texting, no Twitter, no Facebook.) I drank too much. I haunted campus parties at my alma mater, the cautionary ghost of Christmas past. I wasted time in bulk. I was still hung up on my college girlfriend, whom I had boorishly broken up with before realizing that I was in fact in love with her, and who rightly wanted nothing to do with me. I wanted to be a writer, but I couldn’t seem to find my voice.

Mind you: that didn’t stop me from writing. I wrote constantly. You don’t absolutely have to have find your voice in order to write fiction, it just makes the work that much slower and harder and less fun and more grinding. Nothing comes naturally. Everything is forced, the way you force bulbs to flower in winter.

That’s the period of my life from which Warp emerged. But it also came out of a particular moment in American cultural history—it’s a period piece. The year I graduated from college was the year Richard Linklater released Slacker and Douglas Coupland published Generation X. A quarter-century later it’s hard to recover a sense of how radical and powerful those works were at the time, but to me they felt authentically contemporary in a way that nothing else did. I recognized the people in them: like me they thought and read way too much, and did and earned and had way too little. Mainstream middle-class life seemed spiritually and aesthetically bankrupt to them, but any kind of counterculture felt embarrassingly jejune and naive. That left you stuck in between, with nothing to stand on, spinning madly in place.

I wanted to tell my side of that story. Slacker was set in Austin, Generation X was in Southern California, but I was in New England, living a darker, colder variation on the theme. Slacking could be a lot of fun, but it wasn’t as easy as it looked. It required gumption, and resourcefulness, and a gift for easy social connections, and these were gifts I lacked. I wanted to write about feeling trapped in a world where all the answers felt wrong but I couldn’t seem to raise any coherent objections to them; a world where I envied the energetic, hyper-ambitious type A achievers who were constantly coursing past me on their lean muscular legs, but couldn’t imagine joining them; where I knew I was way off the rails but couldn’t figure out how it happened or how to get back on them, I just knew that it was my fault. I wasn’t really a slacker; I was more just a loser.

The most prominent feature of my life at that time, one that is stamped very clearly on Warp, was my awareness of the extreme disjunction between the dreary stasis of my daily existence and the intense, vibrant, magical romance of the various fictions I was reading, watching, and playing: comic books, video games, movies, spy thrillers, science fiction and fantasy novels, and TV—I was obsessed with Star Trek: The Next Generation but I would watch anything. (I am the last living fan of Space Rangers, a gritty show about an interstellar colony, canceled after six episodes in 1993.) Why was the reality I was trapped in so unsatisfying and poorly organized compared to the fictions I consumed so voraciously and in such massive quantities?

The hero of Warp, or at any rate the main character, is named Hollis Kessler. Like a younger and even more inchoate Walter Mitty, Hollis is mentally adrift on a choppy sea of imaginary adventures that echo and mock and annotate the dreary real world around him, reflecting it in reverse, recurring and recurring as leitmotifs. (One of these motifs is drawn from a boy’s-own-adventure-type story that I read as a child, about a fisherman who is dragged under by a manta ray. I searched for this story for years while writing Warp and never found it. Just now I Googled it and found the full text in two minutes: it was “The Sea Devil” by Arthur Gordon.)

Hollis is recognizably descended from a long line of such alienated, mentally hyperactive, outwardly ineffectual young men that includes Holden Caulfield and the nameless hero of Bright Lights, Big City and hearkens further back to Septimus Smith in Mrs. Dalloway, Stephen Dedalus in Ulysses, and the hero of Flann O’Brien’s masterpiece At Swim-Two-Birds, which is the book Warp most strongly resembles (although it’s not nearly as good). Hollis also contains trace amounts of Deborah Blau from Hannah Green’s I Never Promised You a Rose Garden.

Hollis has descendants, too: Quentin Coldwater of The Magicians is of his line. Although I was nice enough to give Quentin magical powers after a chapter and a half, at which point his life gets a lot more exciting than Hollis’s ever did.

I finished Warp in 1996, when I was 27. At around the same time, I had the single greatest stroke of luck in my professional life: a friend of mine got a job at a literary agency. I sent Warp off to her and she agreed to represent it. No bidding wars broke out, but she eventually sold it to St. Martin’s Press for $6,000, and they published it—after a little trademark trouble over what was basically an image of the starship Enterprise on the cover—as a trade paperback in 1998.

I didn’t reread it. I avoided even thinking about it, the same way you instinctively avoid ever listening again to that one album you listened to obsessively while you were getting over having your heart broken for the first time.

From a commercial point of view, Warp was not a success. It earned some respectful reviews, very little publicity and near-zero sales. It never found its audience, and it quickly went out of print and stayed there; to this day, boxes of unsold copies are always turning up in my house, in closets, filing cabinets, and obscure flooded corners of my basement. It was a disappointment, but after a suitable period of mourning I wrote it off as dues-paying and went on to my next book, Codex, which ended up taking another six years. For a decade and a half, I rarely thought about Warp. I didn’t reread it. I avoided even thinking about it, the same way you instinctively avoid ever listening again to that one album you listened to obsessively while you were getting over having your heart broken for the first time.

But when I finally did go back to it, I remembered why I worked so hard on it in the first place. Warp is a careful, orderly portrait of a group of people at the most chaotic, desperately lost time in their lives. It brought it all back to me, the whole terrible authentic texture of that moment: the cheap booze, the black humor, the nameless longings, the alienation, the total poverty, the wasted days, the wasted nights, the circular conversations, the pay phones and old-school video games and pre-grunge alt-rock, and the total conviction that the world was worthless and that everything important happened elsewhere, in fiction and fantasy and dreams and unreal nowhere-places that didn’t exist and meant nothing.

It wasn’t till I was in my early thirties, when I at last had a proper job and a proper apartment and a wife and a nascent career, that I really definitively left that life behind for good. Until then, I think I was a little afraid to reread this book, for fear that I would get sucked back through the rift, back into the temporal anomaly, back into those shadowlands where I fumbled away so much time. Warp is for everybody else who has spent time there, too. And it’s especially for those who are still there now.

From the preface to WARP. Used with permission of St. Martin’s Press. Copyright © 1997, 2016 by Lev Grossman.

Lev Grossman

Lev Grossman is the author of the New York Times bestselling Magicians trilogy. He has been Time magazine's book critic and lead technology writer for over a decade, and he has also written essays and criticism for the New York Times, Salon, Slate, the Wall Street Journal, Wired, the Village Voice and the Believer, among others. He lives in Brooklyn with his wife and three children.