Fashionably Monochrome Mammals: On the Pleasures of Watching Skunks

Sharman Apt Russell Encourages Us to Explore the Wild World Waiting in Our Backyards

Where I live in rural New Mexico, I see striped and hooded skunks regularly throughout the year. I see skunk tracks all the time, every day, around my house, in the fine substrate of the road that leads up to the irrigation ditch, in any bit of dirt or mud, and in the garden enclosed against deer and javelina but not skunk. Skunks regularly explore my wrap-around porch, so that my husband and I watch the animal out one window and then hurry to see it from another. Skunks are often under the bird feeders. We smell them in the morning—the result of some interaction with another animal. We’ve startled them in the early evening. They jump. We jump. Once, jumping back, a hooded skunk fell off the rise of the porch onto his back. Chagrined, he waved his paws in the air like a baby or a pill bug before more calmly turning over and galumphing away. These skunks have never sprayed or shown us any threat behavior. We don’t have any pets for them to worry about. If we live companionably with any wild mammal, we live companionably with skunks.

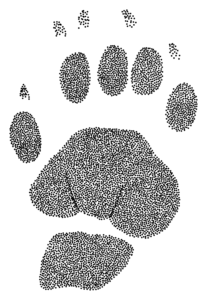

Illustration by Kim A. Cabrera

Illustration by Kim A. Cabrera

Sometimes we see skunk families, mothers and juveniles. Once I saw a mother determinedly waddle and forage while an addled youngster, also determined, dragged under her belly still trying to nurse. Juvenile males finally disperse at three months or so. Juvenile females might stay for almost a year. Mostly we see the solitary skunk. It’s like a fashion show. Something from Chanel. A bit of art deco. That black and white aesthetic.

*

In their discussion of skunks, biologists use the phrase “honest signal.” The white lines of a striped skunk point to its rear end, where two anal glands produce and hold about an ounce of musk each. This concentrated sulfurous fluid can be sprayed with accuracy at targets six feet away and with less accuracy fifteen feet. The four other species of skunk in North America use the same pattern of white on black so as to be easily seen and avoided. This visual cue is enhanced when the skunk raises its tail.

Skunks don’t want to use up their musk and then have to make more musk. They might instead eject a warning smell. They might hiss and stamp their feet. If these strategies don’t work, if that domestic dog keeps barking and barking and coming closer, a striped skunk will twist into a U shape so that both eyes and rump face the threat. From the rump, the skunk emits a stream or multiple streams of a liquid that can burn exposed skin and cause temporary blindness. The odor alone—a mix of rotten eggs, rotting cabbage, burnt garlic, burning tires, and something you can’t quite put your finger on—makes some people gag. Everyone, instinctively, backs away.

I bend down to look more closely, newly aware that I am not alone but profoundly, blessedly, surrounded by the nonhuman.

The result of such a strong defense is that skunks are relatively docile and, as one scientist says, “seemingly carefree.” Adult striped skunks, weighing only a few pounds, have been videotaped eating from a carcass while a fox or mountain lion waits nearby. In one scene, three coyotes circled a skunk on top a dead deer. The coyotes approached, retreated, split up, whined, fussed, nipped forward, nipped back. The researcher noted, “It was hilarious.”

The abundance of skunks must be galling to other predators. Striped skunks range from southern Canada to northern Mexico at an estimate of five to thirteen a square mile. They vary in size and can weigh up to twelve pounds. Typically they have a white stripe that begins at the ears, splits to form a double stripe down the back and joins again at the tail. But that color scheme can vary, with some striped skunks all black, a very few all white, and some brown. Like all skunks, they are active mostly at night. Where the winters are cold, they enter a dormancy or deep sleep, denning from November to March. During this time, skunks must compete to find good dens: housing is one reason they are moving to the cities and suburbs. They particularly like the space under your porch or shed. They like to eat the grubs and insects in your lawn and garden. Dedicated omnivores, they also like small reptiles, small birds, small mammals, crabs, crayfish, eggs, fruits, roots, crops, kitchen scraps, and much more. When I had outdoor cats, they came in through the cat door because they like cat food.

The smallest of North American species, spotted skunks have coats of partial stripes or spots over their back and sides. Their coloring warns predators who get too close, and they further intimidate by doing a handstand on their front feet, performing a split with their back legs, and walking forward in the imitation of a flying carpet. Stop and imagine that for a moment. Google it on YouTube. Spotted skunks also readily climb up and down trees. Western spotted skunks can be found throughout the western United States and southern Mexico. Eastern spotted skunks should be found throughout the eastern United States but are in serious decline for many different reasons—trapping, synthetic pesticides, disease, and habitat lost to agriculture. They are listed as Vulnerable by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) which keeps track of the health of species around the world. (The IUCN lists North America’s four other skunk species as Least Concern, although the population trend of Western spotted skunks and hog-nosed skunks is considered to be “decreasing.”)

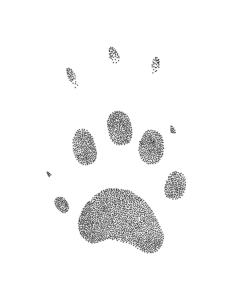

Perfect striped skunk track—left front foot. Photo credit: Kim A. Cabrera.

Perfect striped skunk track—left front foot. Photo credit: Kim A. Cabrera.

One of the largest skunks in the world, growing to almost three feet in length, the American hog-nosed lives in the American Southwest and throughout Mexico. This animal has a powerful upper body for climbing in rocky areas, an elongated snout, and long claws for digging. The back of a hog-nosed skunk is often purely and luminously white, from the top of the head to its beautiful white tail.

The hooded skunk is also confined to the American Southwest and Mexico, looking much like a striped skunk but with softer and longer fur, a longer and more luxuriant tail, and a fulsome furry ruff around the neck. Like every species but the hog-nosed, the hooded skunk has an elegant thin white line or dot between the eyes.

But don’t take any of that too seriously. I have a biologist friend who worked on a study of skunks, with images captured by game cameras. He says that neither he nor the other experts could comfortably identify striped, hooded, or hog-nosed skunks from photographs. Their color variants are just too varied.

*

For some years now, I have been studying the art of wildlife tracking—rather, the identification of wildlife track and sign. My intention is not to follow or trail wild animals. I have no desire to startle or interfere in their secret lives, which are often short and already difficult. Instead, this is the pleasure of standing before a track in the dirt, knowing that a striped skunk or gray fox or long-tailed weasel or mountain lion or blue heron was here recently. Perhaps an hour ago. Perhaps a day or week. I bend down to look more closely, newly aware that I am not alone but profoundly, blessedly, surrounded by the nonhuman.

As hunters and gatherers, we depended on this skill. Perhaps that’s why books and emails are so familiar.

This is a democratic thrill, something almost anyone can have almost anywhere, something you can take up at almost any age or physical condition. I examine the track, using my imagination, my mirror neurons, my reading glasses—matching marks and shapes to meaning and story. As hunters and gatherers, we depended on this skill. Perhaps that’s why books and emails are so familiar.

This is pattern recognition. Long-fingered raccoon tracks practically scream, “Raccoon!” Coyote tracks are often (but not always) distinctly different from those of a domestic dog. The bound of a rabbit—two long hind tracks above two smaller fronts—becomes instantly familiar. Also the sinuous curve of a snake, with pushed up areas of dirt or sand that show the direction of travel.

This is empathy and connection. A quarter-inch pocket mouse track is something you’ll never forget. Those five miniature toes and tiny palm and heel pads. You’ve really entered into another world now, everything else so much bigger, frightening and exhilarating at the same time.

And this, again, is aesthetics. The print of an adult striped skunk is about 1½ to 2 inches long and can look, unnervingly, like a small human hand. On both front and back feet, the three middle toes are partially fused to facilitate digging and face forward, with Toe 1 (on the inside of the track, like your thumb) and Toe 5 slightly splayed to the side. Front and hind tracks usually show handsome claw marks, with the digging claws of the front feet much longer than the hind.

Illustration by Kim A. Cabrera.

Illustration by Kim A. Cabrera.

In the hind track of a striped skunk, the single large heel pad is separated from the palm pad by a distinct seam, a distinguishing mark of the striped skunk in the event I am thinking this might be a tree squirrel. That distinct seam always gives me a ping of satisfaction. Pattern recognition is its own reward.

I also get excited when I come across the relatively rare track of a Western spotted skunk, about 1 to 1½ inches, showing a complex arrangement of four individual palm pads and two heel pads, roughly in the shape of an ice cream cone.

A perfect track—showing all those details of toes, palms, heels, and claws—is something to celebrate because so many tracks are partial, blurred, obscure, distorted by the animal’s speed or sand or mud or whatever. In that case, knowing the common gait of a species can help determine what animal was just here. The spotted skunk is the most carnivorous of all skunks, and its common gait is a bound, the hind feet lifting up and falling above the tracks made by the front feet. Seeing the pattern of a bound might make you decide this is a large spotted skunk and not a small striped skunk. Striped, hooded, and hog nosed skunks more commonly walk. With short legs and a flat-footed emphasis, they toddle and sway. All five species lope and some can gallop as fast as ten miles an hour.

Around my house, skunks frequently break into a rocking-horse lurch that makes them seem slightly drunk or deliriously happy. This, of course, is pure projection.

*

Because the life of a skunk is not really carefree. More than half of wild skunks die in their first year. Sometimes young skunks are killed by predators like bobcats, coyotes, and foxes, while the mother is out foraging. Sometimes male skunks—who do not help raise the kits—find and eat a litter. Captive females will also kill their litters if disturbed soon after giving birth. Great horned owls and eagles hunt skunks. Frequently, skunks get diseases like rabies, distemper, and pneumonia, as well as parasites, which can kill them in their communal dens. (Although rabid skunks rarely bite humans, they carry the virus in their saliva and are a vector in wildlife.) Skunks don’t understand cars at all.

Striped skunk. Photo by Elroy Limmer.

Striped skunk. Photo by Elroy Limmer.

Still, skunks know their own power. Once, looking out on my porch, I saw a small gray fox approach a large striped skunk. The gray fox, I assumed, was an adolescent half-interested in the skunk as prey or playmate. The fox came closer, and closer, and closer, until the skunk stomped with its front feet. This was casual but decisive, up on hind legs, down on the ground. The skunk also emitted a slight odor. A whiff. A warning. And the gray fox catapulted. Just the right verb. Now the fox was a dozen feet away, looking surprised. The skunk may have been laughing. I don’t know. It’s possible. There’s so much we don’t know about animals.

I was laughing, anyway. Admiringly. Another skunk gracing me with its beauty and insouciance.

__________________________________

This essay is adapted from Sharman Apt Russell’s new book What Walks This Way: Discovering the Wildlife Around Us Through Their Tracks and Signs, published by Columbia University Press. Skunk photo by Elroy Limmer, plus a photo of tracks, and two illustrations by Kim A. Cabrera.

Sharman Apt Russell

Sharman Apt Russell teaches at the low-residency MFA program at Antioch University in Los Angeles and is a professor emeritus at Western New Mexico University. She is the author of a dozen books and winner of the 2016 John Burroughs Medal for Distinguished Natural History Writing.