Fae Myenne Ng on the Blurred Boundaries Between Memory and Story

“This is our language in all its alchemic wonder—old stories rebirthing into bigger worlds.”

When I started writing books, my father taught me two terms: small talk and long-ago stories. In Chinese, small-talk conjures up a rapt audience: listening, then gossiping and maybe even lying. Long-ago stories teach me that all writing originates from story. Stories carry time; stories are our ancient heartbeat. When a story is told, truth no longer lives in the present but in the past.

This is our language in all its alchemic wonder—old stories rebirthing into bigger worlds. Labor of love translates to labors in writing. Literature exists inside the in-between moments of hope.

*

In 1992, just ahead of a Nor’easter, I flew out of Manhattan where I’d been living for a decade, home to San Francisco and took my parents to dinner. I’m firstborn to immigrants, first writer, and usually first to say the wrong thing. I wanted to prep my parents for my novel’s debut. They’d worked hard and only had enough English to survive. Murder! Burglar! Cheap! Cheaper!

Their friends, neighbors, and coworkers had kids who read for gossip. Why not—language was a useful tool for gathering information.

We went to Golden Dragon, site of that infamous 1977 Chinatown gang massacre, because they still served Mom’s favorite braised duck. Savory with preserved mustard, fragrant with anise and just a crumble of rock sugar, I could barely wait the half hour to taste that first tender bite of meat falling off the carcass like a morsel of mignon.

In writing, compression of lies can form a book of truth.But first, to deliver my deadly news!

In not-fancy Cantonese, I told them that my book was a work of the “mind,” which was the closest word I knew for “imagination,” but I probably said “brain” because Mom often teased me as a No-Brain American-Born.

I knew the children of their acquaintances would read fiction to claim fact, and I didn’t want my parents preyed upon by gossiping readers who might assume we were the imagined family in the novel: suicidal daughter, adulterous wife, seafaring stepfather. I needed a sword of a sentence to protect my parents.

“Not us.” I attested that the fictional family was a work from my “brain.” But the more I explained “imagination,” the more my book sounded like a half-cooked duck. And like the rallying cry, add oil, coined first in the ’60s at Macao’s Grand Prix, and revitalized during Hong Kong’s umbrella movement, I acquiesced: Maybe I borrowed a bit from our life.

After the lusciously fragrant and supremely juicy duck, after the plate of cut oranges for digestion, after refilling my parents’ teacups, I got back on the plane and on the long flight, I saw my father’s smile and my mother’s askance gaze, when just before leaving, I distilled my heart into one line: The book is about how hard you worked to raise us. For days, I thought about their dignified faces as I trampled through the melting gray snow.

Soon, Mom had her own copy of Bone in the window of her Chinatown clothing shop, a popular post for locals and tourists on busy Stockton Street. One day, a Caucasian woman, touring literary Chinatown, saw it and entered the shop, holding her own copy like a backstage pass.

“My daughter,” Mom beamed.

Tourist-lady pointed at Mom and kept talking about something.

Immigrants sniff out condescension; it’s a language with stink.

When Mom called to relay all she’d surmised about the encounter, she kept laughing, so I joined her. Laughter protects.

A few nights later, Mom gave my book to her niece Maybelle, who—as if the tourist-in-translation—remarked loudly, “But, but… how is it possible that you could have a daughter who can do this?”

“Do you assume,” Mom interrupted, “just because I don’t want to speak English, that I will raise an idiot daughter?”

*

My parents were orphans and came to this country determined to have a family, but the legal and human right to procreate wasn’t theirs. We know the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act was America’s first legislation directed at a nationality, that it was also a historic win for California’s Workingmen’s Party who’d sought to expel the Chinese after the Transcontinental Railroad, but Exclusion’s damage on our sexual health is more devastating because it is eternal.

Exclusion made it hard for men to bring their families from China. Miscegenation laws made it impossible for them to marry and have an intimate life in America. My father called these leftover men with no families Orphan Bachelors. They congregated like pigeons at Portsmouth Square and visited our grocery store; they named us their descendants.

Exclusion destroyed the birthing of the Chinese American family for sixty-one years. My father hollered that Exclusion’s brilliance was that it was bloodless: “America didn’t have to kill any babies, Exclusion made sure no Chinese babies were born.”

*

To circumvent Exclusion, my sixteen-year-old father had memorized a Book of Lies and posed as the paper son of a legal Chinese American father. This was 1940 and his Book of Lies cost $4,000, which is today’s equivalent of $85,000.

My father–the boy carried his book across the Pacific and as an act of rebellion, refused to throw it overboard as ordered when the SS Coolidge slipped under the shadow-cover of the Golden Gate Bridge. Interned on Angel Island, he endured a month-long trial of medical examinations and interrogation before being released to San Francisco to live as an Orphan Bachelor.

Exclusion was repealed in ’43, but for over two decades, a quota limited the annual entry of Chinese to 105 persons. That’s at most nine Chinese persons a month, hardly correcting the imbalance between the sexes. My father named it: Little Exclusion.

I believe my father’s Book of Lies made the road clear for my “self” to write his book of living truths.During the height of McCarthyism, the Chinese Confession Program was offered as an amnesty program to lure paper sons like my father to come forward. My father surrendered his passport, signed an affidavit that he was amenable to deportation. Dad was stripped of his citizenship; he became, to his humiliation, a Resident Alien. In 2001, when he acquiesced to naturalize, I served as his translator. At the end of the interview, the officer asked him to choose one name. He’d lived his whole life with his paper name and he refused to relinquish it.

“Both.” My father insisted, “Both names are mine.”

This taught me about authorship. In writing, compression of lies can form a book of truth.

*

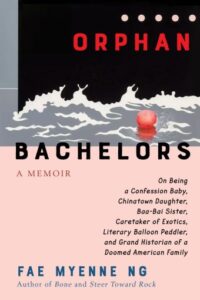

Mom passes before I finish my next book. My youngest brother goes in 2015, and a few weeks later, my father dies. As if sentenced, I write Orphan Bachelors, a chronicle of living memories to hold my dead.

In Chinese, the word “memoir” is made by adding “self” before “story.” I believe my father’s Book of Lies made the road clear for my “self” to write his book of living truths.

When the galleys for Orphan Bachelors arrive, I remember how decades earlier, Mom took a galley of Bone to Great-Grandfather’s grave. She’d steamed a chicken—head, beak, feet intact; she’d fried a fish—head, fins, and tail whole and it looked as if it’d leapt from the river. I can still see my mother placing my book before the tombstone, arranging the food, a pyramid of oranges, and how she burned piles of hell money for Great-Grandfather’s use in the Netherworld’s commissary.

Our immigrant truth: completion in all forms. This ritual was common in my post-Exclusion Chinatown, a sliver of time that no longer exists. When the 1965 Hart-Celler Act lifted the Chinese quota, family reunification was allowed; the influx of the educated class would change the social economic face of immigrant America.

We and our Orphan Bachelors lived in our own vainglorious era when our hope was inflated and our glory, empty. Our parents held tenaciously to the pre-Mao culture they knew, much like how the Sicilians in Manhattan’s Little Italy preserved the world of pre-Mussolini Italy. Our past was lost; our future suspect, so the rituals from the ancient world offered escape from despair. Ritual fortified us.

I no longer have a stove so I can’t cook for my dead, but I do have a beautiful thin-skinned orange which I will deliver along with the galleys of Orphan Bachelors. I will light incense and bow in memory and in ritual gratitude, to my mother, brother, and father, in the line of their departure.

__________________________________

Orphan Bachelors by Fae Myenne Ng is available from Grove, an imprint of Grove Atlantic.