Fabio Pusterla on Discovering a Lifelong Love of Poetry

“I felt as though I’d found a language and voice capable of articulating my inner life.”

It isn’t easy to say what poetry is with any clarity or concision. It isn’t easy and might not be possible or even worthwhile. I have the feeling that when something is too narrowly defined it loses its vitality, as if to define something were to neuter or arrest it. So I won’t try to define poetry.

What I can do is talk about when and how I began to read it and attempt to understand it and even try my hand at writing it. And maybe, just maybe, in this (totally) personal story lies the seed of a more universal definition.

To tell the story, I have to go back nearly forty years. I’m fifty-four now, and I believe I was fifteen or sixteen when I first read a book of poetry. It is in adolescence, after all, that we develop a passion for poetry, as the great francophone poet Philippe Jaccottet argues: that time in our lives when we experience something momentous, a sudden, irreversible break that makes the world which until then had been familiar appear strange and mysterious. Sometimes this break is caused by an excess of tenderness, says Jaccottet, but more often than not the cause is an excess of horror. In either case, excess is involved.

I myself was fifteen years old. At the time I had no idea what was happening to me, and what I’ll try to describe now didn’t start to become clear to me until much later, when one morning about ten years ago I woke up (by the sea, in the south of France) and suddenly realized that the two events in my adolescence that had sparked my love of poetry had taken place almost simultaneously. I’d never made the connection. Nor had it occurred to me that during that same period I’d just begun to read Dylan Thomas, one of the most bizarre and fascinating poets one might encounter.

When something is too narrowly defined it loses its vitality, as if to define something were to neuter or arrest it.

The first event involves my family. I was living with my parents, sharing a room with my sister. I slept facing our bedroom door, which gave onto a narrow hallway. It was one of those old-fashioned doors with a central panel of frosted glass, so that every morning I was greeted by my parents’ shadows: my mother entering the kitchen to fix coffee, my father making his way to the bathroom.

One morning, there was something different about the play of shadows, followed by the sound of my mother’s voice calling out to my father with increasing alarm. Apparently he had locked himself in the bathroom (a habit of his). I climbed out of bed, already aware something terrible had happened. My father wasn’t answering. Through the keyhole I could see part of his body. He was faceup on the floor. I was too scrawny to knock the door down, as I’d seen people do in the movies, but soon enough our neighbor arrived and opened it with his foot. There was my father, lying unconscious, in a puddle of pajamas.

This was the start of a long succession of hospitals, waiting rooms, more hospitals. My father, it turned out, had a terrible illness, a brain tumor, and would suffer from an even more terrible series of side effects, but now is not the time to go into the details of that particular story. My point is, that morning and that locked door signified a profound change for me. Nothing would be the same again, not on a surface level and especially not on a deeper, more interior level. Something had given way; the security of the world, of my world, had been shattered, and I had no words to talk about it.

Not long after, I was riding my motorbike home. I had gone to see my father at the hospital, and on the way back my chain came off. In the process of slipping it back on, my hands became covered in grease. Back then my bike was what we used to call tricked out: parts of it had been modified to make it run faster. A police officer sensed something was up (it didn’t help that I used to cruise around with Easy Rider handlebars and a raised seatback).

He made me follow him to the station, where I sat in a room for a few hours, frightened to death, while he and another officer interrogated me and took apart my poor bike. They discovered all sorts of violations. I had forgotten the whole episode until a few years ago, when a friend of mine, describing her depression, said, “The chain’s come off.” I had been afraid that day, and I sensed that the police officers, though technically right, were abusing their power.

Yet I didn’t say the one thing that might have gotten me out of there sooner. I didn’t say, “I’m sorry, I’m just on my way from the hospital, my father’s dying.” I didn’t tell them because I was incapable of telling them, and perhaps because they were the last people I wanted to tell.

The second incident involved a beautiful, intelligent, rich girl at school. Like all of my classmates, I was madly in love with her. She, of course, looked right past me. But I was besotted. One day, the most popular boy in our group, who would later prove to be, as is often the case, the biggest creep among us, said he’d kissed her—and plunged me into despair. And then… a shadow, something dark and ominous, fell across that beautiful girl. She was losing weight; at a certain point she was nothing but bone. Back then no one talked about anorexia, but that was what we were witnessing. (Unsurprisingly, it was never explained to us.)

The popular boy concocted a plan. Because this thin girl had told a friend that her diet consisted of a single helping of pudding a day, from then on all of us were to bring a package of instant pudding to school and dump the powder mix onto her hair, that hair which I had stared at for months from my desk and which had now grown matted and dull. We were supposed to laugh when we did it.

Did I bring a package of pudding mix? Did I pour it over her head? Did I laugh? No, I don’t think so. But neither did I rush to her defense. I followed my clique with my head down and maybe, from time to time, shot her a pathetic look. At some point I stopped. I didn’t know what to say, neither to her nor to my friends nor even to myself. Nothing that I had learned, no language managed to give voice to what was going on inside me. I was speechless, just as I had been when my father was dying. I still talked, to look at me you wouldn’t notice any great change, but deep down I’d been struck dumb.

Everything that mattered was there, and everything conspired to shed a little light, a little compassion, a little beauty.

During this period, I heard a radio interview with Bob Dylan—I was a fan—and discovered his name was a pseudonym chosen in honor of Dylan Thomas, the Welsh poet who drank himself to an early grave. I immediately hunted up Thomas’s poetry, which in Italy was published in the Oscar Mondadori series and translated by Ariodante Marianni (with whom, many years later, I briefly corresponded). I couldn’t say what, at fifteen, I understood of those strange, visionary poems. On the one hand, maybe nothing. On the other, maybe everything.

What I remember clearly is that as I read those poems (in particular “The Conversation of Prayer,” which I still know by heart) I felt as though I’d found a language and voice capable of articulating my inner life. In Thomas’s words lay the tragedy that had befallen my father, my own bewilderment, the beauty of a girl slipping into the dark, and the tenderness and horror that had robbed me of speech. I, too, was inside the words of that drunken poet, and there in his “star-gestured children” were my friends, who never read. Everything that mattered was there, and everything conspired to shed a little light, a little compassion, a little beauty.

That’s how it began for me. And poetry continues to fascinate me for many of the same reasons. Even now that I teach and publish books on occasion and am supposed to be an expert on the subject, at the end of the day the truth is the same I intuited over forty years ago, and it is, in my view, the one truth that really matters, the one that enables me to tell my students, without feeling as though I’m pulling the wool over their eyes, “Give poetry a chance. You’ll see, it’s talking about you.”

__________________________________

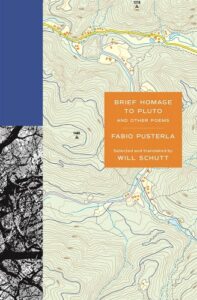

Brief Homage to Pluto and Other Poems by Fabio Pusterla, translated by Will Schutt, is available from Princeton University Press. (From Quando Chiasso era in Irlanda: E altre avventure tra libri e realtà. Edizioni Casagrande, 2012.)

Fabio Pusterla and Will Schutt

Fabio Pusterla is a prolific poet, essayist, and translator, most notably of the work of Philippe Jaccottet. His honors include the Swiss Schiller Prize, the Gottfried Keller-Preis, and the Premio Napoli for lifetime achievement.

Will Schutt is the author of Westerly, winner of the Yale Series of Younger Poets Prize, and translator of My Life, I Lapped It Up: Selected Poems of Edoardo Sanguineti, among other works from Italian. For his translations of Fabio Pusterla’s poetry he received the Raiziss/de Palchi Award from the Academy of American Poets.