Exploring the Moon: Revisiting Apollo 15's Lunar Landing, 50 Years Later

Andrew Chaikin on Three Days Spent in a Geologic Wonderland

Fifty years ago, on July 30, 1971, two Apollo 15 astronauts, mission commander Dave Scott and lunar module pilot Jim Irwin, began the first expedition to the mountains of the moon, landing their lunar module (LM) Falcon at the foot of a towering range of lunar peaks called the Apennines. Equipped with a battery-powered car called the Rover, Scott and Irwin spent three days exploring a spectacularly beautiful, ancient wilderness that proved to be a geologic wonderland. Before the mission they had trained intensively for their explorations, including field trips to California’s San Gabriel and Orocopia mountains, led by scientists who taught Scott and Irwin to use their innate powers of observation as pilots to become lunar field geologists. In this excerpt, we join Scott and Irwin during the second of the mission’s three moonwalks as they drive the Rover up the side of the 11,000-foot mountain called Hadley Delta in search of geologic treasure—and perhaps even a piece of the moon’s primordial crust.

Working with Folio on this new illustrated edition, which comes more than a quarter-century after the book’s original release, gave me a chance to re-immerse myself in the moon voyages, this time with a combination of verbal and visual storytelling. The images in the new edition were selected and prepared by me along with Victoria Kohl. Some of those images are included with this excerpt.

–Andrew Chaikin

*

Sunday, August 1, 1971

8:28 am Houston time

The Rover climbed effortlessly; even now, heading directly up the slope, it was making 6 miles per hour. The plan was to work their way along the mountainside, sampling whatever geologic variety Hadley Delta had to offer. Scott knew what the geologists wanted—a crater that had acted as a drill hole into the mountain, strewn with boulders torn from the flank. But there were no such craters in sight. There was a sameness to the terrain up here; everything was much more worn and subtle than the photographs had led them to believe. Angling along the contour of the mountain, Scott searched for a target, finally spotting a medium-sized crater. There weren’t any boulders, but it would have to do.

When he hopped off the Rover, he almost fell over backward. The drive had been so easy that he had no idea the steepness of the slope they were on. Glancing at his feet, he saw to his surprise that his boots were half-buried in dust, and yet the wire-mesh wheels of the Rover, fully loaded with both of them in space suits, had penetrated only a fraction of an inch. He warned Irwin to be careful. Then he turned around, and what he saw almost knocked him off balance again. They were more than 300 feet up. Hadley Delta’s broad flank swept downward and merged with a bright, undulating desert adorned with the brilliant white rims of craters. Beyond, the Apennines invaded the dome of space. The entire valley was one enormous, incredibly clear panorama: It was the face of pure Nature. And out in the middle of this pristine wilderness, a single artifact: his lunar module. Falcon, that big metal-and-foil bird, was a mere speck.

Three miles from Falcon, Scott and Irwin document the view high on the slopes of Hadley Delta. The lander is barely visible in Irwin’s panoramic photos (see white square at left) but shows up clearly in an image taken by Scott with a 500-mm telephoto lens (inset at right).

Three miles from Falcon, Scott and Irwin document the view high on the slopes of Hadley Delta. The lander is barely visible in Irwin’s panoramic photos (see white square at left) but shows up clearly in an image taken by Scott with a 500-mm telephoto lens (inset at right).

No scene could have conveyed more vividly the reach of this exploration—or the risk. If something had happened to the Rover now, Scott and Irwin would have faced a long and difficult walk to safety, for the LM was more than three miles away—much more than the distance covered by Shepard and Mitchell during their round trip to Cone crater. The whole question of how far to let two Rover-riding astronauts go had consumed hours of pre-mission deliberation. At no time could the men be allowed to drive farther than they could walk back with the amount of oxygen remaining in their backpacks. Because their oxygen supply dwindled as the moonwalk progressed, this walkback limit would be an ever-tightening circle.

Even if the Rover worked flawlessly—and so far, it had done nearly that—there was always the chance that a backpack would fail. In that case, the men would break out a set of hoses that would allow them to share cooling water. The man with the failed backpack would survive on his own emergency pack, which contained about an hour’s worth of oxygen, and if necessary, his partner’s emergency pack, allowing more than enough time for the Rover to race back to the lander. A more dire scenario was that both the Rover and a backpack might break down. For a time, this remote possibility had so worried the managers that they considered writing the mission rules around it—a change that would have severely limited Scott and Irwin’s explorations. In the end, NASA bought the risk of the double failure, knowing that if it came to pass, one of the astronauts would not make it back to the lander alive. But all of this was far from Scott’s mind as his gaze lingered on the view. He felt a wave of excitement: everything was working. He joined Irwin and the two men headed down the slope to the crater.

The mountain was a difficult workplace. The stiffness of their suits hindered climbing; they were reduced to taking small, ineffective hops. With every step, the soft, thick dust fell away from their feet, as if they were walking on the side of a sand dune. A few steps left them nearly out of breath. They spent the better part of an hour here, winning only a few samples for their efforts. There just wasn’t the variety they’d hoped for. They would make another try at Spur crater, but first Scott wanted to get to a boulder they’d spotted along the way.

“Man, I’d sure hate to have to climb up here!” said an amazed Scott as he struggled back up the slope, grateful that the Rover had done so well. “You’d never get here without this thing.” And yet, they had barely begun to scale Hadley Delta. With no haze to block the view, its upper reaches were clearly visible, many thousands of feet beyond. Gazing on that bright frontier, Irwin silently wished they could go higher.

Working on Hadley Delta’s steep flank, Scott photographs a sample before collecting it.

Working on Hadley Delta’s steep flank, Scott photographs a sample before collecting it.

9:38 am

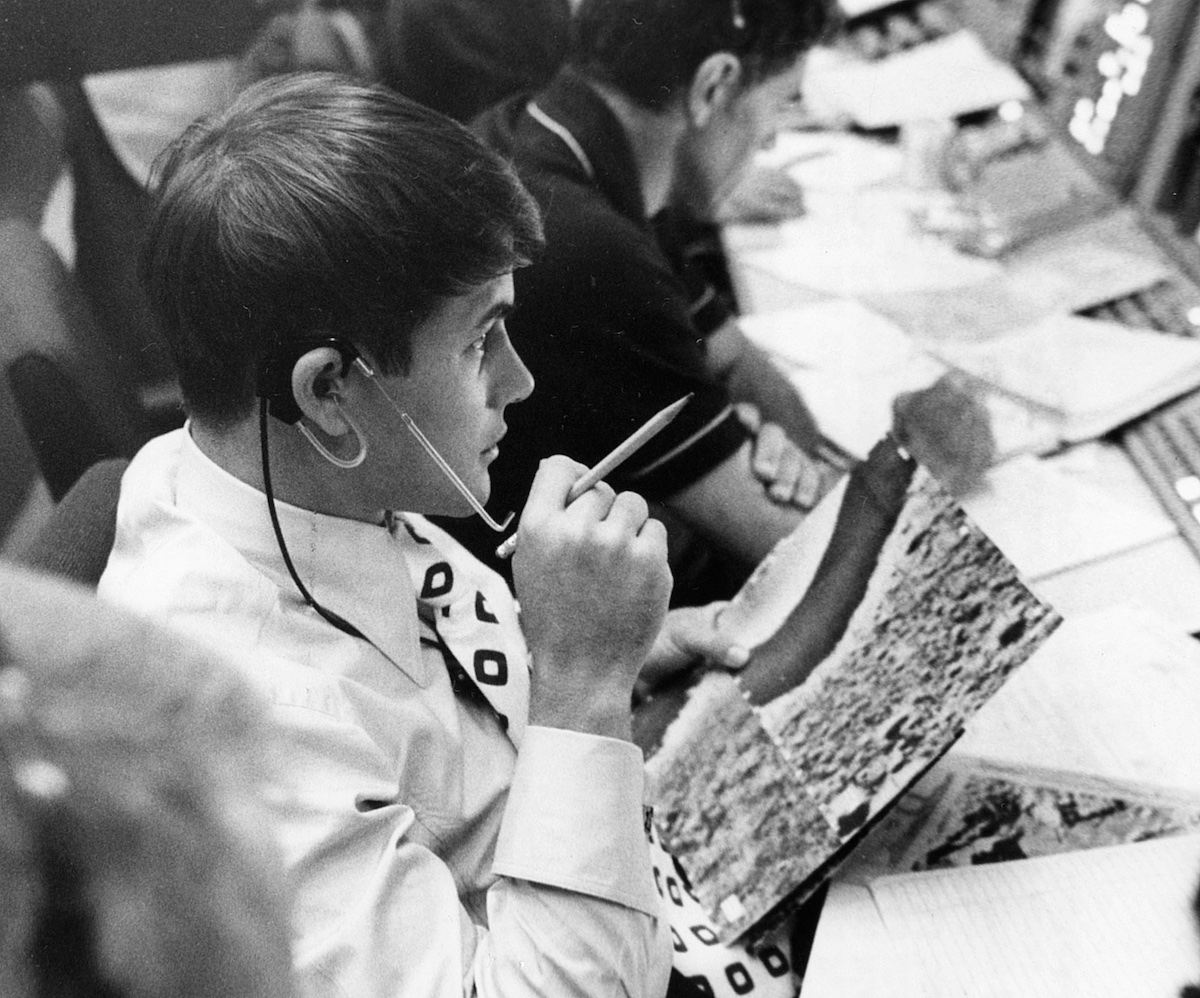

Mission Operations Control Room

Joe Allen sat at the Capcom’s console, studying a photo map of Hadley Delta. Every so often he made a mark showing the best estimate of where the Rover was. His brown hair, short on the sides but longer in front, fell across an unlined forehead. Allen listened intently to the voices of his friends on the moon; at the same time he kept an ear tuned to the conversations in the geology back room. He also had a TV monitor on which the scientists could write him notes—“We’d like a core tube at this stop”—so that if a question came down from the moon, Allen would be ready with the answer. And it was Allen’s job to take the myriad inputs to the astronauts, from the geologists, the flight director, and the flight controllers, and synthesize them into one coherent voice.

Joseph Percival Allen IV, an Iowa-born physicist who came to NASA with the XS-11, was sometimes known as Little Joe, because at five feet six inches he had usurped Pete Conrad by half an inch as the shortest man in the Astronaut Office. At 34, he looked as young as the day he entered Yale to begin working toward his doctorate. In the minds of the geologists, Allen’s assignment as mission scientist was one of the best things that happened to Apollo 15. Allen combined a youthful enthusiasm with a keen scientific mind and an innate sense of people. On the field trips, it was Allen who took the edge off Scott’s driving intensity with a humorous remark. Now, as Capcom, Joe Allen was Scott and Irwin’s link with the back room. No one but he could speak directly to Scott and Irwin; any requests, advice, or questions from the back room had to be spoken by Lovell over the loop to flight director Gerry Griffin and then, via Allen, to the moon. It was no accident that every link in this human chain had been out on the field trips at one time or another, and that each understood the scientific objectives of the mission. Allen in particular understood so well that often he did not even need to ask the back room what to say. He was more than just an ally, Lee Silver would say years later; he was a colleague.

At the Capcom console in mission control, Joe Allen follows Scott and Irwin’s explorations during the second moonwalk.

At the Capcom console in mission control, Joe Allen follows Scott and Irwin’s explorations during the second moonwalk.

Throughout the moonwalks, Allen had tried to convey a sense of support and optimism. He knew Scott and Irwin were working very hard, and he never missed an opportunity to ease the pressure with a comic remark, a private joke. At each new achievement, however minor, Allen voiced his approval: “Extraordinary. Superb.” Deke Slayton had come down on him once or twice for deviating from the spare style of communication that characterized standard pilots’ radio discipline. Allen didn’t let that bother him. There wasn’t any operational reason not to let Scott and Irwin know that he was pulling for them.

He knew roughly where Scott and Irwin were: a few hundred meters east of Spur crater, and slightly upslope from it. Scott had already radioed that he didn’t think it was worth going any farther to the east; they’d already seen as much variety as they were likely to see. They had stopped to sample a lone boulder that was apparently too good to pass up. Allen listened intently as Scott maneuvered the Rover, then stopped. Suddenly the radio link was scratchy, but through the static Allen could hear Scott’s labored breathing. He heard Irwin say, “Gonna be a bear to get back up here, you know.”

“Hey, troops,” Allen said with contained urgency, “I’m not sure you should go downslope very far, if at all, from the Rover.”

“No, it’s not that far,” came Scott’s answer. Irwin added gamely, “I think we can sidestep back up.”

There was no television from the Rover just now, but Allen could picture the steep, powdery slope. He also knew Scott and Irwin wouldn’t give up a prize without a fight. And he could sense that the managers in the back row of mission control were getting worried.

Suddenly Scott called out that the Rover was beginning to slide down the hill. “The back wheel’s off the ground,” said Irwin. Their voices didn’t convey the seriousness of the situation: If the Rover got away from them, it meant scrapping much of the mission, and a long walk back to the LM. Allen listened as Scott held onto the Rover to keep it from sliding down the hill. Now he heard Irwin talking about something he’d noticed on top of the boulder, some kind of green material, he was saying. Allen knew that was unusual, and he wasn’t surprised when Irwin urged Scott to get a sample. The men traded places; now Irwin held the Rover while Scott made his way to the boulder.

While Scott photographs a boulder, Irwin holds the Rover to keep it from sliding down the mountain.

While Scott photographs a boulder, Irwin holds the Rover to keep it from sliding down the mountain.

“Use your best judgment here,” Allen cautioned once more, sensing now that Scott and Irwin had the situation under control. Within minutes, having bagged a piece of their strange find, the men were driving again, heading west toward Spur crater. Time was running out; this would be the last stop on the mountain.

10:00 am

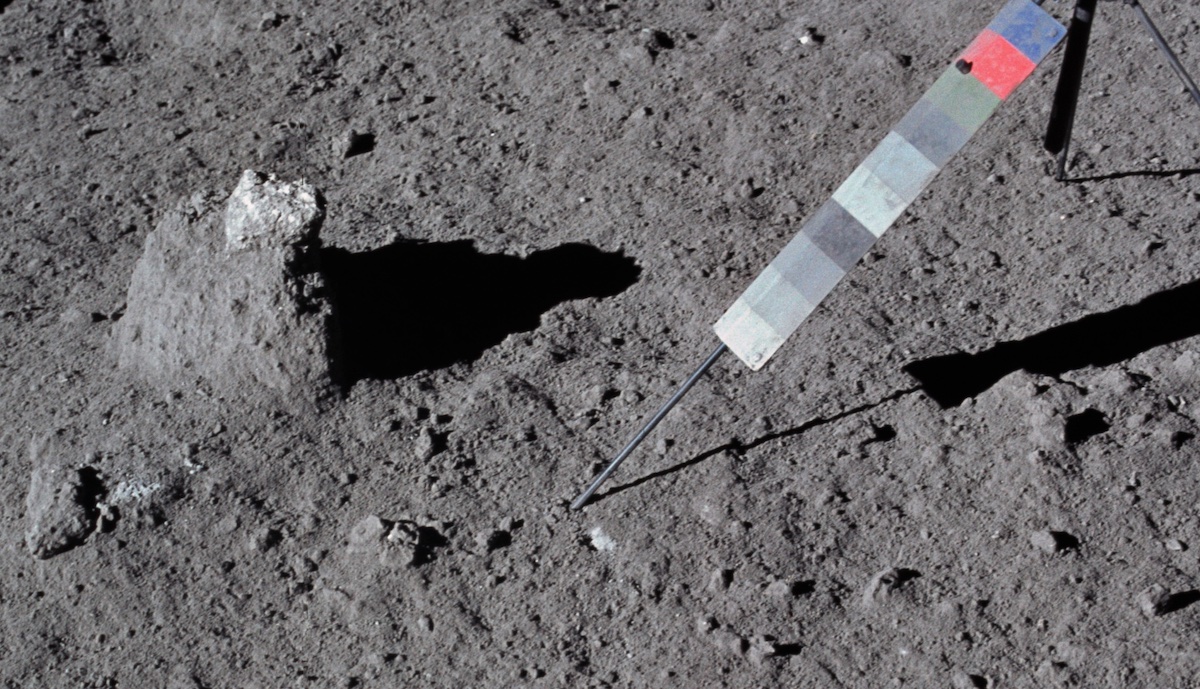

Heading downslope once more, Scott and Irwin angled toward Spur crater and stopped next to the rim of the football-field-size pit. Spur looked promising. There weren’t many big rocks, but there was great variety in the small fragments that littered the soil. Immediately Irwin noticed a white rock, perched atop a small, light-gray pinnacle, that was different from anything he’d seen. Irwin wanted to rush over to it, but Scott was already collecting another rock. Even as Irwin went to help him, he spotted something even more curious. It was more of that green material, like the coating on the boulder at the last stop. What could it be? Moon rocks were gray, or they were tan, or black, or white—but not sparkling light green. To Irwin, a man of Irish descent who was born on St Patrick’s Day and had shamrocks tucked away in the lunar module, a green rock was a special find. There was some debate about whether the color was real—Scott thought their gold-plated visors were playing tricks on them—but they picked it up anyway. It looked like a chunk of basalt, shot through with tiny holes where gas bubbles once frothed in molten lava. But it couldn’t be basalt; it actually yielded to the pressure of Scott’s gloved fingers, which left streaks in its surface. Not until the rock was unpacked in the Lunar Receiving Laboratory would the men see that it truly was green, and that it was actually made of tiny spheres of glass. Even among moon rocks, it was a rarity. And in time, the story it would tell, of eruptions from the hidden depths of the lunar interior, would hold geologists spellbound.

But just now, Scott and Irwin’s attention was riveted to the strange, white rock Irwin had seen earlier. As they approached, they strategized about the best way to collect it. Irwin suggested lifting it off its dusty pedestal with the tongs. Scott did so, and he raised it to his faceplate to inspect the find, which was about the size of his fist. It looked fairly beaten up, and it was covered with dust, but as he grasped it with his gloved fingers some of the ancient coating wiped off, and he could see crystals: large, white crystals. Suddenly–

“Ahhh!”

“Oh, man!”

–both men realized what they had discovered. The rock was almost entirely plagioclase. Exposed to light for the first time in untold eons, its white crystals glinted in the sun, like the ones they had seen in the San Gabriels. This was surely a chunk of anorthosite, a piece of the primordial crust. Scott radioed the news.

“Guess what we just found. Guess what we just found. I think we found what we came for.”

“Crystalline rock, huh?” prompted Irwin.

“Yes, sir,” said Scott.

“Yes, sir,” repeated Joe Allen, like a brother at a revival meeting. After describing the rock in detail, Scott placed it in a special sample bag by itself. Of all the rocks brought back from the moon this one would be the most famous. To the geologists, it would be sample number 15415, but to the world it would be known by the name bestowed upon it by a reporter covering the mission at the space center: the Genesis Rock. In time, probing the treasure with electron beams in their laboratories, the geologists would peg the rock’s age at 4.5 billion years. If the moon was any older than that, it wasn’t much older; the solar system itself was thought to have formed only 100 million years earlier.

The Genesis Rock, perched on a pedestal of grey dust before Scott and Irwin collect it, will prove to be a piece of the moon’s primordial crust.

The Genesis Rock, perched on a pedestal of grey dust before Scott and Irwin collect it, will prove to be a piece of the moon’s primordial crust.

Scott couldn’t hear the geologists’ ecstatic reactions in the back room, but he didn’t need to. And Spur had even more to offer. As they made their way along the crater rim they happened on one remarkable find after another, poking out of the dust. Scott sounded like a rare-coin collector who had stumbled across a treasure chest in the attic. “Oh, look at this one!” Scott told Allen what was already clear: “Joe, this crater is a gold mine!”

“And there might be diamonds in the next one,” said Allen, a gentle reminder that Scott and Irwin could not linger here. They were getting close enough to their immutable walkback limit that Allen was telling them to press on. Now Allen radioed that Irwin’s sample bag was about to come loose—everyone in mission control could see that on the big screen, and they worried that all those priceless samples might tumble into Spur crater. Precious minutes were lost as Scott cinched it up. With less than fifteen minutes remaining, Scott and Irwin looked hopefully at a boulder that lay perhaps a dozen yards farther along Spur’s rim, the only large rock in sight, and therefore the only rock for which the geologists could be sure of its place of origin. Undoubtedly it had been torn from the floor of Spur.

Just now, Allen passed up word from the back room: forget the boulder; they wanted them back at the Rover, using the rake to collect a bunch of walnut-sized fragments. Scott eyed the boulder. He told Irwin to go ahead and start raking; in the meantime he went into high gear. A short run along Spur’s rim brought him to his quarry. Working on stolen time, he clicked off Hasselblad pictures of it from every angle. There wasn’t time to hammer off a piece, but he spotted a small fragment in the dust—obviously knocked loose from the big rock—and got his sample after all. He hoped the geologists would be able to figure out where it came from by studying the pictures. Scott turned and ran back to join Irwin in his work. He hated to leave. It was a frustration he would feel again and again on the moon, just as he had that first day in the Orocopias with Silver: there was never enough time.

_________________________________________

Excerpt from The Folio Society’s edition of Andrew Chaiken’s A Man on the Moon: The Voyages of the Apollo Astronauts.

Excerpt from The Folio Society’s edition of Andrew Chaiken’s A Man on the Moon: The Voyages of the Apollo Astronauts.

Andrew Chaikin

Andrew Chaikin is an American author, speaker and space journalist. He was born in 1956 and grew up in New York and studied geology at Brown University. He went on to work at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory at NASA and was a researcher at the Smithsonian’s Center for Earth and Planetary Studies before he became a science journalist in 1980. Chaikin has written numerous articles about space exploration and astronomy and is best known for his book A Man on the Moon: The Voyages of the Apollo Astronauts (1994, Folio 2021).