Excavating Emily: Janice P. Nimura on What Draws Biographers to Certain Lives

And Why Some Mysteries Have to Stay That Way

Feature image from Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

When you write a biography, and if you’re lucky enough to share it with readers, you need a good origin story. How did you decide to write about this? people ask. How did you first meet these people? And by extension: Why are some lives remembered? What preserves a story, like a fossil, for a historian to discover and excavate? What draws the excavator to the story? And how do they figure out what it means once they dig it up?

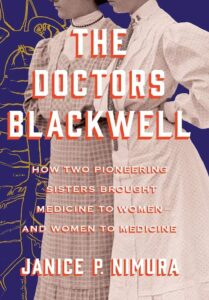

Sometimes it’s obvious. A year ago I published The Doctors Blackwell, a double portrait of Elizabeth and Emily Blackwell, sisters and pioneering female physicians—Elizabeth the first woman to receive an American medical degree in 1849. The First Woman Doctor is easy to enshrine. If you were the kind of third grader who liked reading Great Lives for Kids, there are several versions of Elizabeth on the shelf. She’s always slim and well-dressed, bending solicitously toward a grateful patient, and holding a stethoscope. (She’s also always woefully oversimplified, but that’s a different essay.)

In third grade I was over in the fiction section with equally iconic women like Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle and Mary Poppins. Until six years ago I had never heard of Elizabeth Blackwell. I may be the only person who met Emily Blackwell first. Emily: third woman doctor, eternally eclipsed by the older sister who recruited her to pursue medicine, knowing the path was too steep to walk alone. Emily, who took to medicine for its own sake, not just to prove something about what a woman could do.

I may be the only person who met Emily Blackwell first.

I met Emily in chapter 15 of Lilian Faderman’s To Believe in Women: What Lesbians Have Done for America—A History. As a writer whose work has always competed for space with marriage and motherhood, I was intrigued by a certain kind of Victorian border-crosser: the woman who sought intellectual and professional fulfillment outside the lines of convention and then found emotional fulfillment in the form of a “Boston marriage,” a committed domestic partnership—sometimes physically intimate, sometimes not—between two women whose professional successes enabled them to sustain a household without the economic need for a man.

Faderman is a venerated professor, gay rights activist, and prize-winning historian and author who embraces her well-earned reputation as the “mother of lesbian history.” I was browsing in the Sophia Smith Collection of Women’s History at Smith College when I picked up her book. “Emily Blackwell earned a medical degree in 1854, when she was twenty-eight years old and should have been in panicked pursuit of a husband,” I read. A woman who earned a medical degree in antebellum America? Medicine was my own path-not-taken; the idea of a woman who had stayed the course so long ago was astonishing. I read on—and met Elizabeth Blackwell a couple of pages later. It was the beginning of a new book project, five years of archival exploration and storytelling about 19th-century medicine, complicated sisterhood, and the rights of women.

Emily’s inclusion in Faderman’s book was due to her life partnership with Elizabeth Cushier. The Blackwell sisters founded the New York Infirmary for Indigent Women and Children in 1857 and added its Women’s Medical College in 1869; Cushier studied at the college and then joined the faculty. By 1882, she and Emily shared a household and the care of Emily’s adopted daughter. Emily was 56 when Cushier, a decade younger, moved in.

The written record of their 30 years together is sparse, but the contentment they found in each other is clear. “You ought to have a partner like Dr. Cushier,” Emily wrote to her niece Alice Stone Blackwell, another formidable single woman. The two physicians mentored students and performed surgery side by side, and Cushier’s assiduous attention to their domestic affairs freed Emily to focus on the leadership of the infirmary and the college. “I do not know what Dr. Emily would do without her,” wrote Mary Putnam Jacobi, another trailblazing physician and a member of the faculty. “She absolutely basks in her presence; and seems as if she had been waiting for her for a lifetime.”

A pride flag on Cushier’s grave, no matter how lovingly planted, is a one-sided conversation. So is a biography.

But Emily Blackwell didn’t meet Elizabeth Cushier until the steepest ascents of her medical career were behind her. Like her sister Elizabeth, Emily had insisted on studying medicine among men, even when her classmates chalked “Strongminded Woman” under her caricature on the blackboard. She was forced to seek admission not once but twice when, after a single term, her first college asked her not to return, having changed its mind about the wisdom of welcoming female students. She interned with Edinburgh’s James Young Simpson, one of the most prominent gynecologists in Britain.

Back in New York, the Blackwell sisters opened the first hospital staffed entirely by women, and later added a women’s medical college that was ahead of its time in its progressive curriculum and emphasis on practical instruction. Emily successfully lobbied Albany for the funding to support these institutions. At the time, she was arguably the most accomplished female surgeon in the world. And once the infirmary and its college were underway, Elizabeth Blackwell moved permanently to England and left Emily in charge.

Emily Blackwell was a supremely accomplished, world-changing professional long before she invited another woman into her life; in the book I wrote, Elizabeth Cushier appears for the first time on page 262. But without Cushier, Emily would never have ended up in Faderman’s book, and I might never have met her.

In the fall of 2019, as I was finishing the research for The Doctors Blackwell, I made a pilgrimage to Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn. The main gate is a multi-spired gothic fantasy that looks like someone forgot to build the rest of the cathedral. Backlit against a mackerel sky, it was the perfect portal to a whole city of forgotten stories.

We are drawn to stories that resonate with something inside ourselves.

I was looking for the Cushier family plot. When I found it, tucked into the side of a hill, I realized I wasn’t the only visitor who knew about Elizabeth Cushier and her “own dear doctor,” Emily Blackwell. Someone had planted a rainbow flag on her grave.

I felt the prickling presence of something I couldn’t name, something that moved me. Here in this vast cemetery, itself a postage stamp within the vaster, heedless city, someone had taken the time to bring a symbol of recognition and celebration to this specific spot. At the base of the marker lay a dragonfly wing, iridescent in the sun. I laid it gently on top of the stone, my own tribute to two supremely independent, capable women who loved each other.

And then I thought, what would those two long-dead doctors make of these rainbows? Or Faderman’s book? Or mine?

Impossible to answer, but unanswerable questions are important. I spent five years studying the Blackwell sisters, two women born in the 1820s. Everything I learned came from the pages they and others left behind. There was no way to ask, How did you feel when you wrote that? Do you still feel that way? How do you want to be remembered? A pride flag on Cushier’s grave, no matter how lovingly planted, is a one-sided conversation. And at a more complicated level, so is a biography.

We are drawn to stories that resonate with something inside ourselves. For Faderman, it was Emily Blackwell’s partnership with another woman. For me, it was the Blackwell sisters’ pioneering persistence in the art and science of medicine. I read their letters and journals, and those of their brothers and sisters; I read their ledgers and articles and meeting minutes, and as much as I could find of what others had written about them. I read about leeches and laudanum, about freethinkers and suffragists, about family dynamics. I traveled to Bristol and London and Edinburgh, to Paris and to Geneva, New York. And then I tried to put all the pieces together into something that feels like the truth.

Is it? I hope so. But my truth and yours are different. I have been lucky to share the Blackwell story with many audiences, and many people have asked, why don’t you write more explicitly about Emily being gay? My answer to that is, both Emily and Elizabeth Blackwell based their lives on the rejection of labels, and both were fiercely private people. There are no written sources that are explicit about their most intimate relationships. Cushier, Emily told her sister, “is like a younger sister or elder daughter to me.” Whether this was a statement of truth, or a smokescreen, or the words of a woman whose cultural moment prevented her from seeing herself clearly, I don’t know. And I respect Emily Blackwell too much to guess.

What I do know is that both sisters were extraordinary and need to be remembered. A biography is a life story refracted through the lens of a storyteller. The storyteller’s perspective clings to the telling the way earth clings to a fossil. And the reader brings her own lens, and her own truth, when she opens the book.

___________________________________

Janice P. Nimura’s The Doctors Blackwell is out now in paperback.

Janice P. Nimura

Janice P. Nimura is a book critic, independent scholar, and the American daughter-in-law of a Japanese family. She lives in New York City.