Excavating Dora Maar: On the Afterlives of Art History's Forgotten Women

Anne Boyd Rioux Considers How We Tell the Stories of Picasso’s Mistresses

Francoise Gilot, who died recently, is remembered as the only one of Picasso’s mistresses to leave him. She emerged triumphantly from their relationship, in fact, becoming a successful artist in her own right, as the lengthy obituaries of her attest.

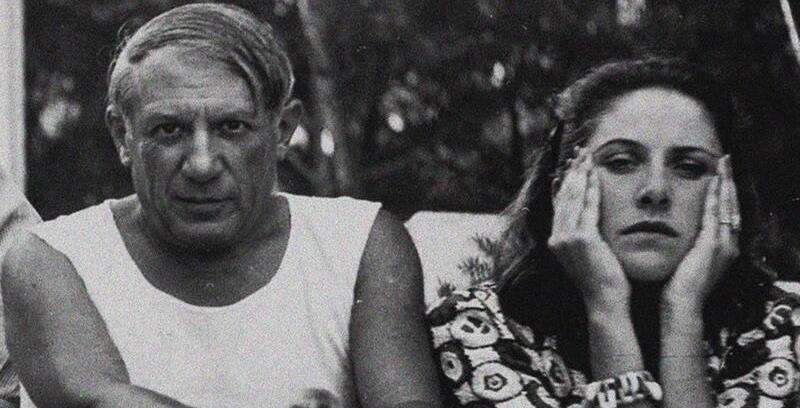

His previous mistress, Dora Maar, who died in 1997, did not fare as well. She was the “weeping woman,” frozen in despair in his portraits of her as well as in life. In contrast to Gilot’s story, hers is the tragic one of a woman destroyed by a male genius.

Both women were, in fact, extraordinary artists who deserve to be remembered as much more than Picasso’s former mistresses. Yet, they both knew they would never escape that designation. Gilot tackled the problem head-on by publishing the bestselling Life with Picasso, while Maar turned inward, leaving others to mythologize her. As a result, we know frustratingly little of Maar’s life, at least in the English-speaking world. While Gilot’s memoir and a biography based on conversations with her are available in English, there are no books in print about Maar’s life except the authoritative Dora Maar by Victoria Combalia, published in Spanish in 2013.

I was lamenting this fact a few months ago in the kitchen of Dora Maar’s house, which Picasso gave her in 1944 as he abandoned her for Gilot. I had just come down to make some tea when I stumbled upon the writer Adam Gopnick and a few others getting a tour of the house, located in Menerbes, France. Gopnick agreed that there should be a biography of Maar in English. “You should write one,” he said. I laughed. I don’t even speak French.

He was the sun god around which the art world orbited. She had to extinguish her own light to reflect his.

The tour moved on, and I put the kettle on the stove. Yet, his words lingered in the air.

*

I have a thing for forgotten women. In fact, I went to the Dora Maar House to work on a project about one. But increasingly I found Dora’s deep brown eyes calling to me from the books about her in the library, mostly in French. I found two in English that piqued my interest, but as I dug in, I found their portraits of Maar disappointingly partial, suffering, as so many women’s life stories do, from a dearth of primary sources.

My hunger for more of Dora followed me around her vast, four-story house during the month I was in residence there as a fellow of the Nancy B. Negley Artists Residency Program. There is something like haunting that happens to the (would-be) biographer. In my case, Dora became a kind of absent presence for me during the long hours I spent virtually alone in her big, empty house. I believed for a while, in fact, that I was sleeping in her room. I later discovered that she slept next door, but the prospect made me feel as if I owed her something in return for her hospitality.

*

The story of Dora Maar’s life I encountered in those books in the library told the maddening tale of a woman of great talent led astray by the cult of (cruel) male genius. When she met Picasso in 1936, she was part of the Surrealist inner circle and had exhibited her dreamlike montage photographs at major exhibitions. She was politically active, passionate, and already an experienced lover (after her affair with the famously kinky Georges Bataille). She approached Picasso as an artist, asking him to pose for her, which he did. I love this part of her story. But it wasn’t long before she let him convince her that photography was a lesser art than painting. Sadly, she exchanged camera for canvas, becoming his student after all.

She also became a major subject of his art. Early on he made simple, adoring portraits of her, as in Dora Maar on the Beach, in which she appears whole, intact, and lovely, an alabaster Venus with eyes welcoming the viewer into a sea of tenderness. Then, amidst his work on Guernica and the emotional turmoil of Picasso’s continued affair with Marie-Thérèse Walter, the mother of his second child, he made the dozens of “Weeping Woman” portraits. In these Dora appears with distorted, chopped-up features. The most famous one, in the Tate, is painted in putrid yellow, absinthe green, and tomato red. Books on Maar tend to view this famous series as grotesque misrepresentations that perform a kind of violence. They now grace the walls of the world’s most famous museums. (A major retrospective of Maar’s artwork at the Pompidou and the Tate in 2019 attempted to correct the “weeping woman” image of her, but she has received an anthill of artistic recognition compared to that given to Picasso’s “weeping woman” series alone.)

With Picasso, Dora was at the center of the universe. He was the sun god around which the art world orbited. She had to extinguish her own light to reflect his. When he tossed her aside, she was left in darkness. She suffered a breakdown and endured three weeks of electroshock therapy, after which, some say, her former vitality was gone.

Her fifty long, post-Picasso years are summed up quickly in the accounts of her life, as if the important part of her story is over. She clung to a Paris apartment full of his artworks—a fortune, if she wanted to sell them, which she didn’t—and a crumbling mansion in Provence that he had given her. She lived with a cat, read religious texts, and produced what are generally considered unimportant paintings. More or less a nun, she left the house only to attend mass, having found in God the only possible replacement for Picasso.

Was this all there was to say of her long life after the demise of their relationship?

*

How do we to tell the stories of Picasso’s (or other famous men’s) women, especially today when we yearn for stories of women persevering, even triumphing, in the face of male dominance? It’s not enough to simply paint them as victims, devoured and spit out by the great men they loved. We want more from—and for—them. This is why Gilot’s story is so appealing, and Dora’s so troubling.

What do we expect from the women of the past we are drawn to? What shape should their lives take?

In my quest to know the Dora who survived Picasso’s cruelty, the woman whose presence I still sensed in the house, I turned to the memoir Picasso and Dora by James Lord, who knew her in the 1950s. He was mesmerized by her. Through his depictions, we see her vibrant eyes, her smile that dazzled like the sun. She is eccentric but hardly mad. How to reconcile her continued vivacity with the image of an ascetic nun that pervades other accounts of her post-Picasso life?

In my last days at the Dora Maar House, I took Victoria Combalia’s Dora Maar down from the shelves. I found a substantial section on the last part of her life. Aiming my camera at the pages, all in Spanish, and aided by a translation app, I began to see bits and pieces of her come to life. I discovered a woman who did rise from the ashes, just not as publicly as Gilot did.

Combalia portrays Dora as seeking and gradually finding peace and stability in the wake of Picasso. Through reading and meditation, she reestablished the connection with God that had been severed by her years as Picasso’s doormat. “After Picasso, there is only God,” Dora said, which others have seen as evidence of her obsession with the artist. But Combalia argues that she turned to God for the unconditional love she could not find in him or any man (as many other artists and writers have). “She was moving from a hectic and cyclothymic life, full of turbulence and emotional upheavals with Picasso, to a meditative, balanced life that she wanted, free of anguish,” Combalia writes. Who wouldn’t want that for her?

What do we expect from the women of the past we are drawn to? What shape should their lives take? The fact that Dora Maar turned to God and lived alone, apparently celibate, for the rest of her life made her pitiful, even possibly mad, to her contemporaries and those who have written about her since her death. But Combalia looks more deeply in her biography, which is based on interviews with Maar and her personal papers—and which should be translated into English.

By the time I left the Dora Maar House, I knew that Dora wouldn’t be following me. She was happy to stay there, where she had found so much peace. I do still carry her with me, though, in the form of a picture taken in the 1950s, the only image that I found of her smiling. It shows her standing outside her house in Menerbes. We should all be so lucky to find refuge in such a beautiful place.

Anne Boyd Rioux

Anne Boyd Rioux is a professor of English and the author of three books, most recently Meg, Jo, Beth, Amy: The Story of Little Women and Why It Still Matters (Norton, 2018). She is currently writing a book about the American anti-fascist writer Kay Boyle. You can find her at anneboydrioux.com and https://lettersfromanne.substack.com/