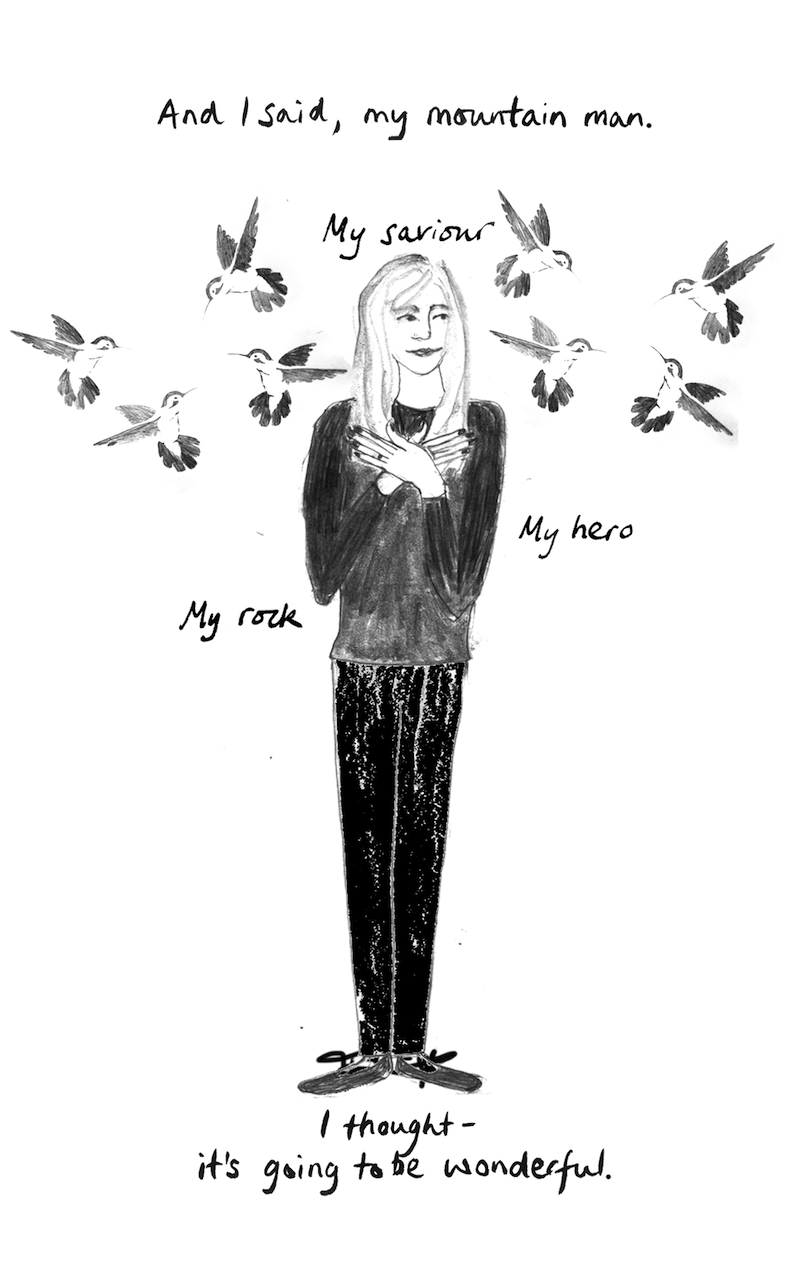

Everything Will Be Perfect if We Move to the Western Wilderness

From Bella Pollen's Memoir

The following is from Bella Pollen’s memoir, Meet Me in the In-Between, which tells of a life shuttling back and forth across the Atlantic, trying to find the extraordinary in the ordinary.

Some nights their faces swam in front of me like a photo line-up of the NSPCC’s most wanted. Anya, who hid Beefeater gin in the back of the pram; Sticky Lisbette having sex in my bed; Munchausen Sal squeezing blood from her own thumb into baby’s nappy so she could raise the alarm of internal bleeding—and this was only a sneak preview of the au pair saga. Had these girls always been psychotic or had they turned into child-loathing, passive-aggressive sociopaths after a month or so embedded in my family? Too many hands had rocked my cradles, but with four babies now, what were my options?

I would live and die for these small beings I had brought into the world, but if they were to make it through park outings without being molested by the royal swans or a trip to the department store without being dragged through the teeth of the escalator, they were always going to need a more a attentive eye than mine. Out here in the San Juan Mountains, though, things would be different.

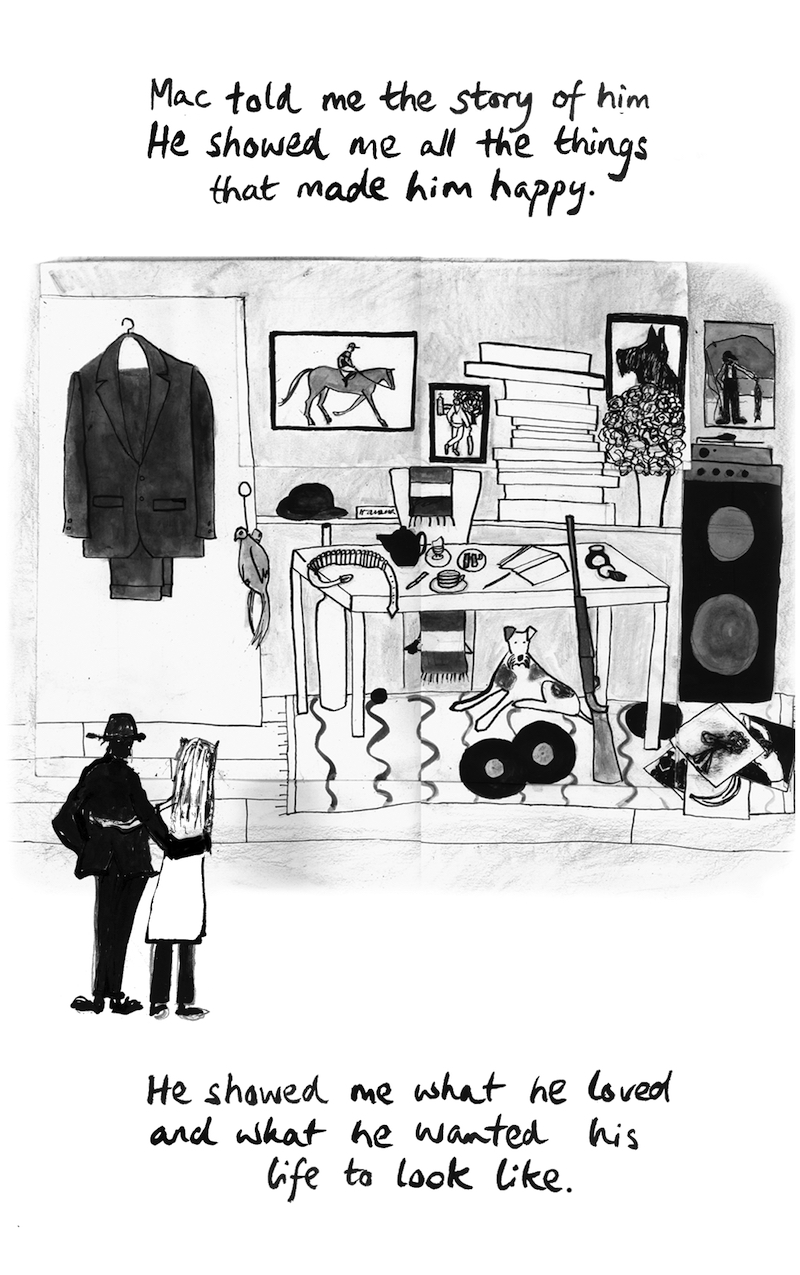

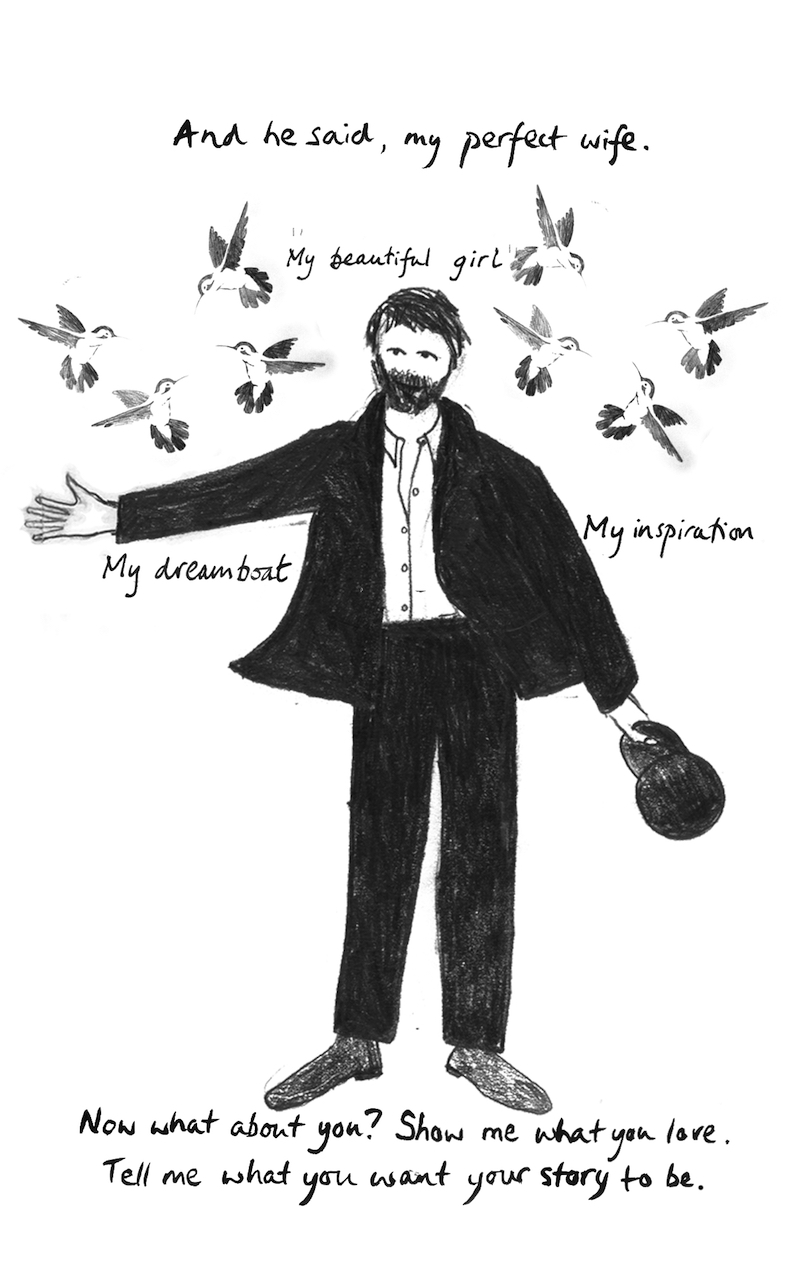

Here, 9,000-feet high, at the end of a 20-mile dirt road, in a rolling meadow of wild flowers, Mac and I had found a place like nowhere else. When a snip of homesteading land cropped up for sale one day, we bought it over the telephone. Two years, a thousand scribbled drawings, a posse of locals, and a lake of Budweiser later, Mac decapitated the last of the monster thistles from around the doorway and carried me over the threshold of the home we’d built together—a big barn made of reclaimed pinkish wood with a view onto a million acres of wilderness.

*

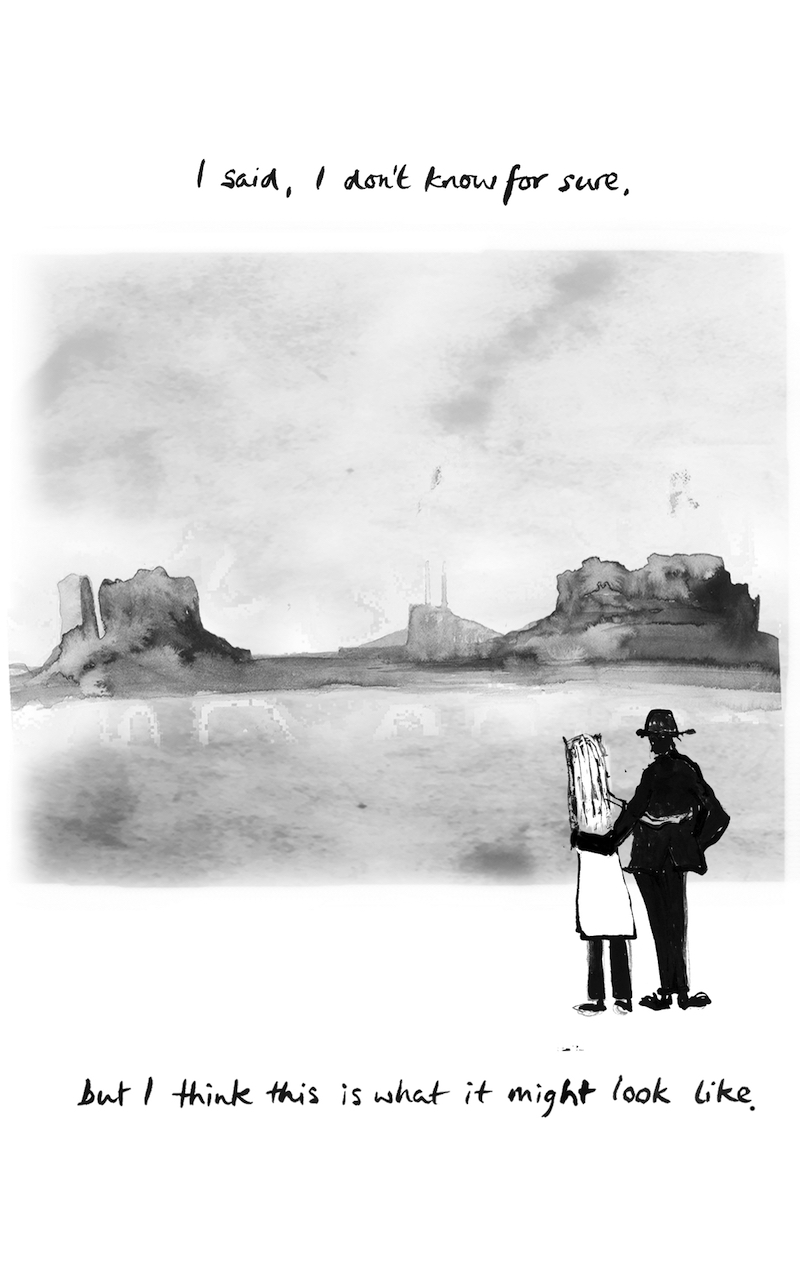

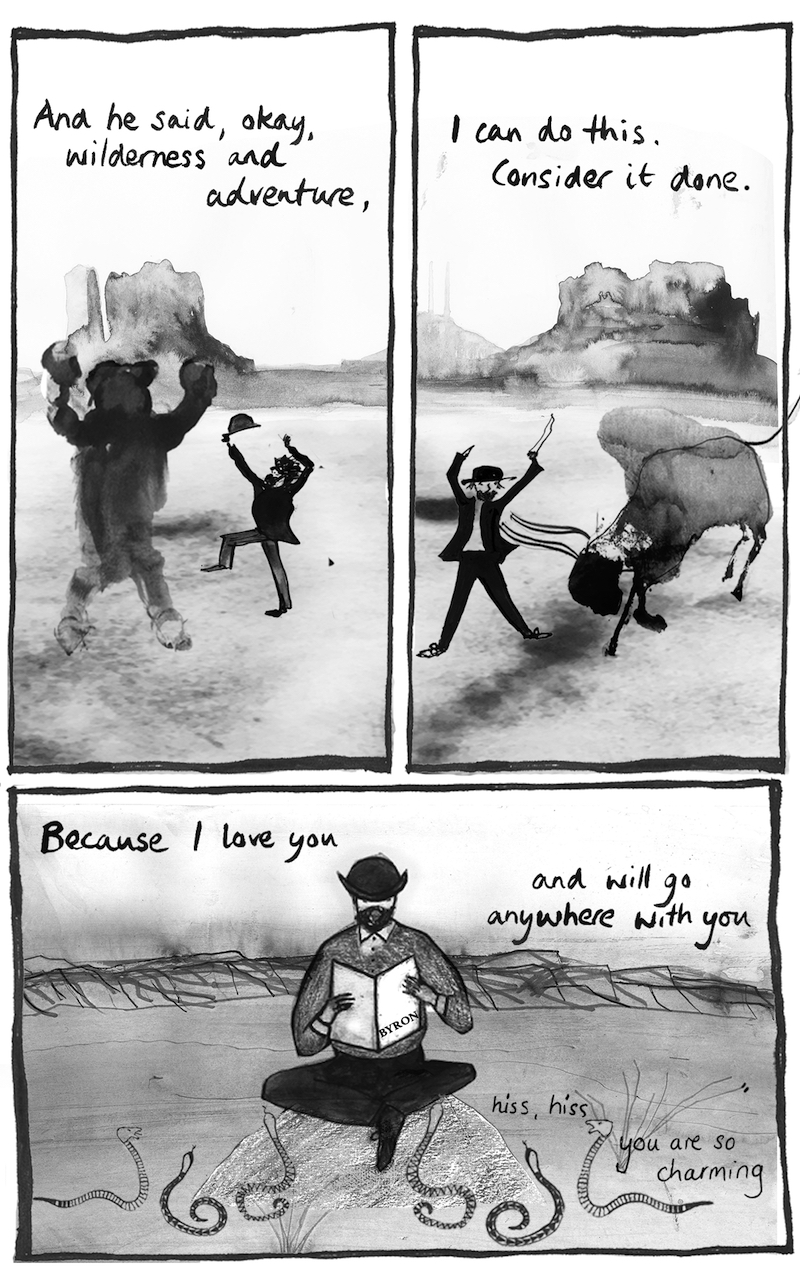

After the nervy tightness of London, the vastness of the West was like a cool liquid running through my head. Here was a place we could lose ourselves without getting lost. A place where itchy feet didn’t feel mutually exclusive with raising a family. A place to focus on creating something new, even if that something was made out of words and sentences instead of color and thread. And truth be told, it was time to get on with it.

Sudden withdrawal from any drug comes with side effects. A month after our CEO closed down my business, my body shut down. In the weeks that followed, plank-like, except for a comic limb twitch or two, I was wheeled off by Mac to a succession of doctors who tweaked and cracked their way to a diagnosis. It was idiopathic, psychosomatic. It was dilemmatic, melodramatic. Either way, the episode trapped something in the base of my spine that I still felt from time to time. Pain, sharp as a cattle prod, a reminder of something lost, something integral to my sense of self.

But I had it all worked out. Up at the barn, Mac would run his business remotely and shoot pack rats. I would write at the table in front of the big window while keeping a benign eye on the kids, as they skipped through the Indian paintbrush and charmed grass snakes with flutes carved from the branches of a fallen aspen tree. I had little difficulty picturing myself stuffing hay into pillows and trimming our winter coats with marmot fur, while the children churned butter out of dandelions and perfected their needlepoint. Forget Thai take-out, foraging would become our new byword. We’d live off the land. Tickle trout onto our dinner plates and garnish them with chanterelles harvested out of the still, quiet forests of the Rockies.

Alas, the marmots were ridden with fleas, the trout laughed in our faces, and the only grass snake in the valley died of cardiac arrest at its first human encounter. Isolation meant no playdates for the kids, and after a few days they turned gloomy and began draping themselves over the furniture like pressed flowers, demanding microwaved dinners and mourning the lack of Gymboree. I myself was disappointed to find that a move to the wilderness was no cure for my feeble housekeeping skills. Laundry piled high and dust patterned the floors in crop circles, while the big glass window quickly became ticked by battalions of kamikaze insects. If weaving up and down the mountain for supplies took, well, six hours, bulk buying resulted in the autopsy drip of rotting salad and bowls of penicillin-sprouting lemons.

They say that on retirement former powerhouses of multitasking quickly deteriorate to the point where they can barely manage a chore a day. Looking back, I marveled at how much I got done while in the business of fashion. I hacked up cloth, wrangled with lawyers, got hammered with factory workers, smarmed up to buyers, hauled Freddie the dyspeptic tailor out of his bed in North London twice a week, and still had time for a vibrant second career as agony aunt to all fifeen of my employees. Post-fashion I managed one thing only—fractional movements of a mouse over a pad. I used to have a range of excuses for devoting too little attention to my kids, not least of which was the geographic location of my office, but the day I went to work in my head was the day my mothering skills really died on the vine. Oh, I soothed and patted and hugged and praised, but there were robotics involved and my children were not fooled.

My pioneering spirit lasted a week before I caved in and posted a sign in our local Walmart:

HELP REQUIRED: MUST LOVE KIDS. EXCELLENT DRIVER. NONSMOKER ESSENTIAL.

Enter Pamela.

She blew in one stormy day sporting an orange sun visor—which, it would transpire, she wore all year round, indoors and out, irrespective of the weather.

“Keeps the goddamn flies from biting, ya know?” she said, shaking off her wet plastic poncho to reveal an interview outfit of spangly boob tube over a pair of velour leggings that bagged fatally around the ass whilst obscurely managing to give her a camel toe at the same time.

Pamela was a lanky woman, with dye-stained hair, intelligent eyes, and the slight look of a cod fish around the mouth. Originally from Texas, she had a drawl that bent every phonic rule in the book and she delivered it in startling monotone, uninterrupted by a single um or any other speech disfluency. Right from the start she made it clear that helping with kids was out of the question.

“They’re a little rich for my taste,” she stated, as though I’d offered her a sugared plum along with her cup of coffee. “And don’t go expectin’ me to give these up”—she pulled out a crumpled pack of Pall Malls—“because a true addict never quits.” She struck a match and drew on her cigarette with relish. “Now listen up, because this shit you only get to hear once.”

Over the next hour, Pamela laid claim to a tough life, and there was no question that it showed in her slate-colored teeth and mottled gums. I swear this woman had wrinkles in places I’d never seen before. She alluded cheerfully to halfway houses, a daughter long since given up for adoption, and an old flame living in a Detroit penitentiary whom she liked to visit from time to time. “So you get why I don’t come cheap,” she concluded, stretching out her sandals and admiring a far-row of toes playfully crawling one over the other like unruly piglets. “But I’m fast and I won’t slam you on the hours.”

Everything about Pamela should have been heartbreaking, but nothing was. I looked at the flimsy wad of my manuscript and couldn’t think of a single reason not to hire her.

*

Pamela was soon working for us three times a week. She arrived mid-morning in an ancient Dodge stippled with rust. She drove like a Pulp Fiction character: insanely fast, Sonic Burger in hand, fag jammed between her lips. It’s a long and deeply rutted road from town up to our barn, and the Dodge didn’t always make it intact. It was not unusual to see her freewheeling the final hundred yards down to the deck holding her burning exhaust pipe out the window and hollering at the children to fetch duct tape.

The interior of her car was an artwork that might have been short-listed for the Turner Prize under the title Everything I Have Ever Consumed. The upholstery was yellowed by nicotine, the seats dotted by cigarette burns and tacky with Gatorade. If the clutch was sometimes difficult to depress it would be due to the pile-up of browning banana skins wedged beneath it. The floor was littered with spent cartons of red wine, and every time Pamela opened the driver’s door, she triggered an avalanche of crumbling Styrofoam.

This might not have been the greatest CV for home help, but it turned out she was afiend with the broom and had an Olympian skill for folding laundry, even if everything she washed came out of the machine the same color.

When I suggested the dividing of loads into whites and colors, she declared: “That’s a myth. I don’t buy into any of that holistic, organic crap.” Before long the whole family was dressed à la Pamela in outfits of fatally bagging greige, but who cared? I was back working. As far as achieving something, we are all given a finite amount of time. The more of it I spent in the real world, the less accessible my imaginary one became. I still didn’t understand how this trade-off worked, but I knew that each time I went through the magic wardrobe, I was leaving lost children behind me. Pamela might not be the obvious choice to bring balance to our lives, but help, as the saying goes, comes in unexpected ways.

__________________________________

From Meet Me in the In-Between, by Bella Pollen, courtesy Grove Atlantic. Copyright 2017 by Bella Pollen.

Bella Pollen

Raised in New York, Bella Pollen is a writer and journalist who has contributed to a variety of publications, including Vogue, Bazaar, Spectator (UK), the Times (UK), and the Sunday Telegraph (UK). She is the author of five novels, including the bestselling Hunting Unicorns and the critically acclaimed The Summer of the Bear. She lives and works between the United States and England.