“Every Border is a Story.” On Dividing Lines Both Real and Imagined

James Crawford Considers the Continuing Relevance of Literature’s Borders

The oldest written story of a border dates back to 2,400 BC, carved in cuneiform into a half-meter-tall pillar of crystalline limestone. It tells of an argument between two cities over a stretch of Mesopotamian barley fields called the “edge of the plain”—now part of the deserts of Iraq. For a century and a half, these fields changed hands, most often violently. The pillar, which was placed on the border between the cities, gave only one side of the dispute. Among other details, it explained the origin of the line it demarcated: that it was drawn by the father of all the gods, at the very beginning of time. Territory, it said, was eternal.

That the pillar was hacked out of the ground and lost beneath the sands for millennia before finally making its way to the storage rooms of the British Museum suggests rather the opposite. Only translated in 2018, this pillar’s inscription—which also features the earliest use of the phrase “no man’s land”—perfectly captures the true nature of the many borders that have come to divide and define our world. Before they are mapped, or drawn, or marked, they begin as an idea. No political border ever just exists in the world. It can only ever be made. Or, rather, it can only ever be told. One way or another, every border is a story.

The first border story that I came to know was something of a dark fairy tale, a barrier that haunted news reports, culture, films and music when I was a boy: the Berlin Wall. For 28 years, it was the ultimate edgeline of the Cold War. When it finally fell, in November 1989, I was eleven years old. I remember watching footage of Berliners dancing along the top and hacking holes in the concrete. It would take a year or so before the wall was actually demolished. Yet everyone talks of the “fall” in terms of that one night. The wall was still there, but the story had changed. In a matter of hours, it had lost its power.

*

A few years later, as a teenager in the mid-1990s, I developed an obsession with another border. By chance I picked up a copy of Cormac McCarthy’s The Crossing while browsing in my local bookshop. The second novel in his “Border Trilogy,” it tells of Billy and his younger brother Boyd, who move with their parents to a ranch on the border between New Mexico and Mexico in the early 1930s. When Billy turns sixteen—the same age I was then—a she-wolf, come north from Mexico, begins to attack the family’s cattle. Billy rides out with his father in an attempt to trap the wolf, but she eludes them. Increasingly the boy goes alone to check and re-set the traps. When he finally catches the wolf, and finds that she is pregnant, he resolves not to kill her, but to take her back into Mexico, to set her free.

So begins a journey into a spare and harsh border landscape of high mountain passes and endless prairies. Billy’s days are spent riding; his nights, hunkered down by open fires, staring into the unfathomable eyes of the wolf, eyes that burn “like gatelamps to another world.” This quest comes to a quietly tragic end and afterwards, Billy traverses the high country in listless mourning, becoming a creature of the borderlands, a ragged figure existing in an in-between state, rootless and alone.

No political border ever just exists in the world. It can only ever be made.

McCarthy writes of that landscape as a portentous, atavistic place, where the fabric of the world grows thin and time drifts out of meaning. When Billy first crosses into Mexico, he sees one of the concrete obelisks erected in the mid-nineteenth century to mark the international boundary line: “in that desert waste it had the look of some monument to a lost expedition.” Over the border he finds the land “undifferentiated in its terrain from the country they quit yet wholly alien and wholly strange.” He knows the land and knows that it has not changed. Yet somehow, across that invisible line, everything is different. Wholly alien and wholly strange.

Reading The Crossing at sixteen marked the beginning of something for me—the moment that I began assembling an “archive” of borders. My archive takes the haphazard form of pages torn out of magazines and newspapers; it is scattered across notepads and scribbled in the margins of hundreds of books. Much of it is filed away, erratically and inefficiently, in my own head. Memories of things I’ve read, or heard, or seen; novels, histories, songs, films, documentaries. My interest is always piqued when a border appears. (It even has one physical item—a probably fake, thumb-sized chunk of the Berlin Wall which I bought on eBay ten years ago).

Central to my archive’s existence is an attempt to interrogate what a border really is. This same philosophical question is posed perfectly by Ursula le Guin in The Left Hand of Darkness, as a disenchanted diplomat wonders, “How does one hate a country or love one?… I lack the trick of it. I know people, I know towns, farms, hills and rivers and rocks, I know how the sun at sunset in autumn falls on the side of a certain ploughland in the hills; but what is the sense of giving a boundary to all that, of giving it a name and ceasing to love where the name ceases to apply? What is love of one’s country; is it hate of one’s uncountry?”

This search for the moment at which “country” becomes “uncountry” propels my fascination with borders. Not least because the power of separation extends far beyond the visible world. Borders begin within us, long before they are ever inscribed in the land. Writing during the First World War, Stefan Zweig describes crossing a border as a profound shock to the senses. As he travels by train from Austria into neutral Switzerland, he writes of how “It took but a few minutes from one station to the other, but in the very first second one was sensible of such a change as that of suddenly stepping from a closed suffocating room into invigorating and snow-filled air, of something like a giddiness which trickled palpably from the brain through all one’s nerves and senses… In the moment of crossing the border I was already thinking differently, more freely, more actively, less servilely.” Zweig’s response is echoed by Fred and Cat in Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms, as they flee the war in a rowing boat on Lake Maggiore, leaving Italy for Switzerland:

“Isn’t it a grand country? I love the way it feels under my shoes.”

“I’m so stiff I can’t feel it very well. But it feels like a splendid country. Darling, do you realise we’re here and out of that bloody place?”

“I do, I really do. I’ve never realised anything before.”

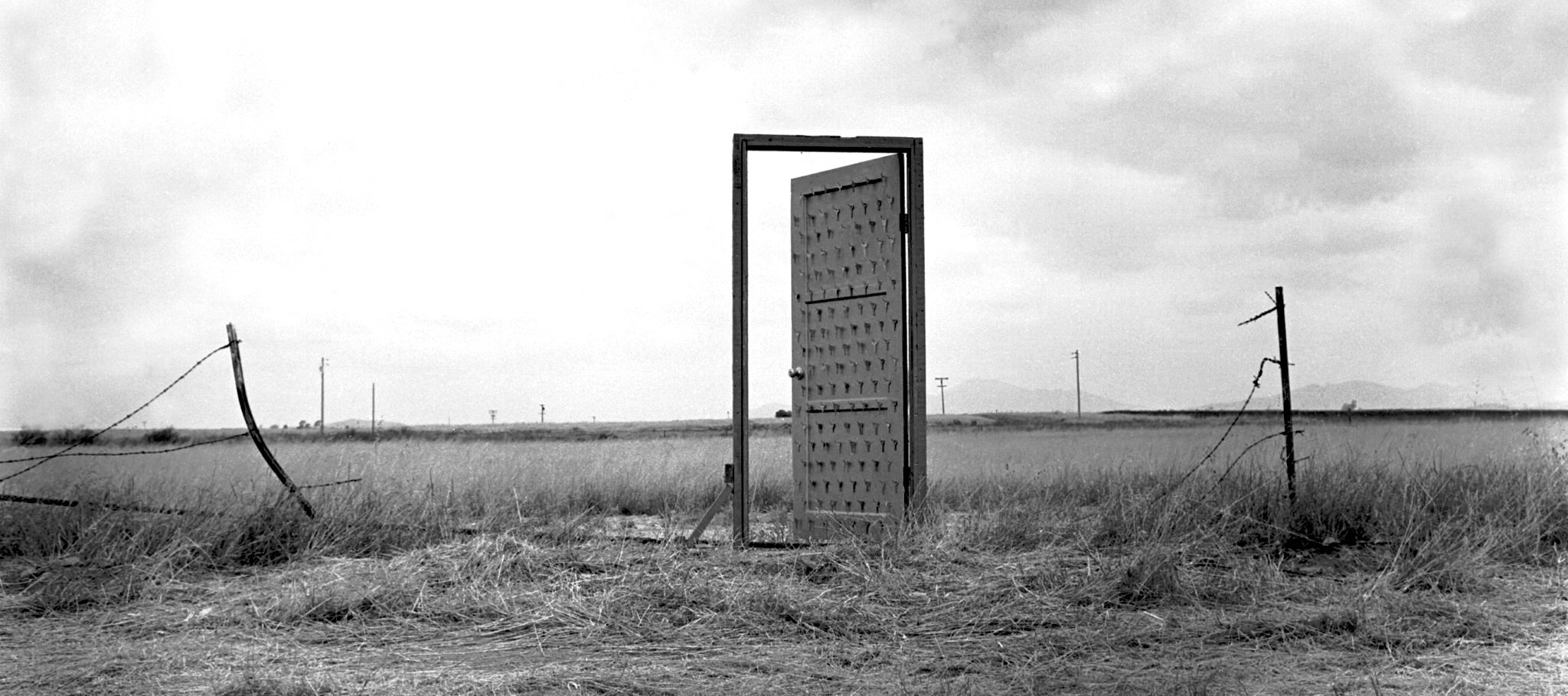

In circumstances of flight or escape, it is impossible to ignore the sheer psychological weight of border crossing; the strength it can take to pass through to the other side, and to face the consequences. Fred and Cat’s crossing came back to me when I read Mohsin Hamid’s Exit West. Once again, the protagonists are lovers, Saeed and Nadia, resolving to leave a violent and disintegrating country behind. But on this occasion, the boundary between conflict and freedom has become far murkier. Hamid imagines secret doorways emerging all across a war-torn eastern world and leading directly into western cities from London to San Francisco. As Nadia prepares to enter one, she is faced with its terrifying equivocacy: “drawing close she was struck by its darkness, its opacity, the way it did not reveal what was on the other side, and so felt equally like a beginning and an end.”

It is the particular nature of borders that they are “equally like a beginning and an end.” They are, instantaneously, points of arrival and departure. Exits and entrances. Darkness and light. This is what Amitav Ghosh terms “the enchantment of lines.” In The Shadow Lines, he is brilliant at playing up the absurdist notions of borders in the context of the Indian Partition, predicting his country’s impending calamity through a bitter family feud that results in a wall being built to “partition” a house in East Bengal. The narrator’s grandmother, who lived in this bisected house as a girl, recounts how she would tell stories to her younger sister about what life was like on the other side of the wall—that everything was upside down and back to front, that their estranged family “began meals with sweets and ended them with dal;” that their books started at the end and ended at the beginning.

Years later, as the grandmother prepares to fly between East Pakistan and India, she asks if she will be able to see the physical border from above. When her son laughs at her and says she’ll just see clouds and fields, she snaps back at him, “What was it all for then—Partition and all the killing and everything—if there wasn’t something in between?” The irony today, however, is that there very much is something in between. Still under construction and stretching for over 5,000km, the border fence between India and Bangladesh is set to become the longest in the world. Whereas India’s other border to the west, with Pakistan, has so many floodlights it’s clearly visible in photographs taken from space.

It is one of the benefits of my (albeit partial) archive that it allows me to track this changing nature of individual borders over time, and not least that site of my teenage obsession, the United States’ southern border with Mexico. When McCarthy describes its 1930s incarnation in The Crossing, “you can ride clear to Mexico and not strike a crossfence.” Come the 1960s, when it appears in Jack Kerouac’s On The Road, it is filtered through the excitable, strung-out prism of the Beat generation, and has become a gateway to freedom: “Behind us lay the whole of America and everything Dean and I had previously known about life, and life on the road. We had finally found the magic land at the end of the road and we never dreamed the extent of the magic.”

Another half century on, however, in Valeria Luiselli’s Tell Me How It Ends, we see how these once spare and empty borderlands are filled with the infrastructure and traces of those trying desperately to cross northwards, and others who are dedicated to stopping them. “We see a trail of flags that volunteer groups tie to trees or fences, indicating that there are tanks filled with water there for people to drink as they cross the desert…As we approach Animas, we also begin to see fleeting herds of Border Patrol cars like ominous white stallions racing toward the horizon.”

It is remarkable how often writers don’t just reflect the events that have come to beset our modern, bordered world, but anticipate them. In John Lanchester’s 2019 novel The Wall, an unnamed island country (but clearly Britain) has surrounded its entire ten thousand kilometres of coastline with a massive concrete wall—designed to keep out the rising sees of a climate catastrophe, and successive waves of climate refugees arriving on innumerable rubber dinghies. In Lanchester’s future, there is clear foreshadowing of Britain’s present migrant crisis—not least the recent government slogan “Stop the Boats”—but taken to an even more brutal extreme.

Another, far earlier English novel—published in 1826—predicted a now equally familiar modern crisis: a late-21st century world stricken by a deadly pandemic. In Mary Shelley’s The Last Man, follow-up to Frankenstein, a new disease is consuming the world. Borders become at once crucial and immaterial. They are closed or hardened, yet still remain biologically porous. Soon, as Shelley writes, “the nations are no longer.” The pathogen breaks through, and borders shrink from countries, to cities, to towns, to villages, to your own house, your own room, until finally, territory means nothing beyond the immediate landscape of the self. “Our minds, late spread abroad through countless spheres and endless combinations of thought, now retrenched themselves behind this wall of flesh, eager to preserve its well-being only.”

Borders are always there to be rewritten.

Increasingly, in our current febrile political climate, aspects of many novelists’ imagined dystopias are emerging as realities. In the wake of US Supreme Court’s reversal of the judgement in Roe vs Wade, for instance, it is hard not to think of Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, especially those passages that depict the very early days of the emerging dictatorship of Gilead. When Offred and her partner and daughter attempt to flee north across the border to Canada and show their fake passports to the border guards (doctored to present them as a married couple, and their daughter “legitimate”), Offred watches the “two soldiers in the unfamiliar uniforms that were beginning, by then, to be familiar… standing idly beside the yellow-and-black-striped lift-up barrier.” In that heightened, surreal moment, “everything was the colour it usually is, only brighter.” It is a reminder—as accounts emerge in today’s United States of an “abortion underground” aiding the movement of medicine and patients across borders and state lines—of how little society needs to shift on its axis to send the world we thought we knew out of kilter.

While these examples of speculative fiction have an uncanny knack for predicting elements of our present, they are not alone in their ability to assume new, contemporary relevance. Recently re-reading Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, I was struck by a number of passages describing the migrants of the 1930s Dust Bowl. Steinbeck captures something universal and timeless about forced migration; what it means to leave a life and a spent land behind; to strike out towards the unknown with a mixture of hope and despair. “They were not farm men anymore,” he writes, “but migrant men. And the thought, the planning, the long staring silence that had gone out to the fields, now went to the roads, to the distance.”

With the United Nations Commission on Human Rights announcing in 2022 that the number of forcibly displaced in the world had passed 100 million for the first time, Steinbeck’s writing, even 80 years on, still offers a vital reflection on the wrenching experience of migration all across the globe, as set against the hardening attitudes of those who watch them come. “There was panic when the migrants multiplied on the highways. Men of property were terrified for their property. Men who had never been hungry saw the eyes of the hungry. Men who had never wanted anything very much saw the flare of want in the migrants… and they reassured themselves that they were good and the invaders bad, as a man must do before he fights.”

In countless places across our unequal world, and in particular those border intersections between global north and south, we are, sadly, seeing this same panic in the eyes of the watchers, and this same slide back into simple stories of good on one side, and bad on the other. Such binary stories have always shaped how we live, not least in attempting to explain the arbitrary locations of our borderlines. Yet seeing how literature has explored, confronted, challenged, mocked, and unpicked borders demonstrates, continually, that that the forms they take are not, in fact, eternal. Tales of walls and fences and barriers—built to hold off “the flare of want”—may hold political sway right now. But they are not inevitable. Borders are always there to be rewritten.

__________________________________

Excerpted from The Edge of the Plain: How Borders Make and Break Our World by James Crawford. Copyright © 2023. Available from W.W. Norton & Company.

James Crawford

James Crawford is a historian, publisher, and broadcaster. He worked at Scotland’s National Collection of Architecture and Archaeology for over a decade and is the writer and presenter of the BBC One documentary series Scotland from the Sky. He lives in Edinburgh.