Erika Howsare on Finding Inspiration in Headlines

“As a poet, I love the pithiness of headlines—and beyond that, I love found language of all kinds.”

This first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

This week, my email inbox has brought to my attention the following:

Deer seen flying through the skies in Utah

North Olmsted resident debates culling deer population

Dwarf deer: This mini Mississippi buck is the trophy of a lifetime

Are wolves to blame for the deer decline?

Michigan deer population continues to grow, hunters in decline

Woman gored by mule deer buck in front yard

Neighbors rescue deer stranded on Big Spirit Lake

Famous Richmond deer allegedly killed by poacher: ‘Such a punch to the gut’

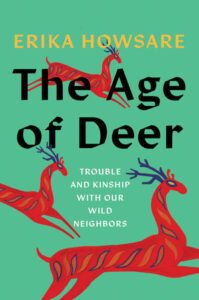

These headlines are a microcosm of some of the issues I covered in my nonfiction book, The Age of Deer. I’d had an inkling, even before writing the book proposal, that deer were involved in all manner of controversies, contradictions, and human strivings. That was what got me interested in them. But I didn’t know too many specifics. When I started researching, one of the first things I did was to set up news alerts on deer and several other related terms.

Within a week, I had a rough outline of some of the major roles deer play in our world. They are victims; they are pests; they are something to hunt as well as something to study and protect. They are the targets of culling operations and the objects of sentimental love. They are trophies and intruders. It was all there in the news cycle.

As a poet, I love the pithiness of headlines—and beyond that, I love found language of all kinds. I’ve used it in my poetry quite a bit. It’s not just the “you can’t make this stuff up” factor; it’s also a kind of documentary urge, the Duchampian idea that putting actual parts of the world in front of a viewer, or reader, is as meaningful as inventing something from scratch. It’s evidentiary; it lets a person see for herself what’s happening out there, as deer crash into schools or contract Chronic Wasting Disease or damage farmers’ crops.

I didn’t need to read every story to get the point: Scanning the headlines was a constant reminder of how wide and deep the subject of deer really is—how thoroughly it extends throughout our lives.

Of course, I did read many of the stories, even as the research process also demanded that I read scientific articles, poetry, and historical accounts. I had several books going at any one time, but meanwhile, the news alerts never stopped supplying me with the gloriously odd minutiae of the human relationship with deer (“This Town Wants to Put Its Deer on Birth Control”; “Poachers Hunt Deer from Taxi”). And they echoed the seasonality of things. Hunting-related news reached a fever pitch in fall and “leave fawns alone” PSAs peaked in late spring.

I wanted at one point to include long lists of these headlines (I love arranging them into ready-made mini-essays). Or I could imagine them as section dividers—formal frames that would remind the reader of the world bubbling in and around the text. In the end, the book quotes only a few of the headlines directly. But the conflict and struggle they express are there underneath, an invisible part of its foundation.

Beyond that, many of the stories I tell more fully in the book came right out of those news alerts. I noticed, for example, spates of stories about deer getting stuck in human spaces, like houses and stores. I contacted a few of the people who’d been involved in these incidents, interviewed three of them, and ended up including one of those interviews in the book. It’s a conversation with Anthony Worley, a security guard at a North Carolina courthouse who subdued and successfully removed a deer that crashed through the door near Worley’s post.

It was a strange scene in the courthouse as Worley and a co-worker held down the deer until help could arrive. He told me, “One of the clerks of court, she was kind of petting it on its head, saying ‘Poor baby, it’s okay, it’s okay.’” Worley had a less tender encounter: “It kicked the ever-living fool out of me.” (The deer was eventually released with only minor injuries.)

The texture of the way people talk, the particularity of place names—these are the real-world gems that make nonfiction writing joyful, like a spin through the best thrift shop in the world.

I still haven’t turned off those alerts. I’d miss the weirdness of the daily stew they deliver. Just this morning: “What Could Have Caused Melvin the Deer to Attack in Andover?”

_____________________________________

The Age of Deer by Erika Howsare is available now via Catapult.

Erika Howsare

Erika Howsare is a writer, journalist and teacher. Her essays, reviews and interviews have appeared in publications such as the Los Angeles Review of Books and The Rumpus, and she is the author of two collections of poetry, How is Travel a Folded Form? and FILL: A Collection (with Kate Schapira). She lives in the Blue Ridge in central Virginia.