Erik Axl Sund is Actually 2 Emotionally Astute, Middle-Aged Punk-Rockers

Speaking with the Collaborative Authors of The Crow Girl

I arrived at the Penguin Random House offices in New York a half hour early for my interview with Erik Axl Sund, the nom de guerre of Swedish writing duo Jerker Eriksson and Håkan Axlander Sundquist, and proceeded to continue reading their mammoth debut work of fiction, The Crow Girl, newly published in the United States by Knopf (the book was published as a trilogy in Sweden, though written as a single entity). Having received the book less than a week prior to the interview, I hadn’t yet finished it—though I had already guessed, and the authors let slip a confirmation, a central mystery in the novel.

The Crow Girl is a psychological thriller that’s been frequently compared to Stieg Larsson’s Millennium trilogy, a comparison the authors don’t altogether mind. The books’ similarities are obvious: they take place in Sweden, feature traumatized and abused women as main characters, involve lots of police work that is alternately technical or vague, and, perhaps most importantly, they employ great storytelling as a way to engage with social issues. But where Larsson’s work propels itself forward through plot, The Crow Girl turns inwards far more often and dwells in realms that will make most readers abstractly ill: child pornography, molestation, incest, murder, torture, extreme bullying, and cycles of abuse are just some of the cheerful topics tackled alongside serious mental illness. Foremost among these is the concept of what is now called Dissociative Personality Disorder, immortalized in inaccurate movies like “Me, Myself, and Irene” but ultimately portrayed faithfully in The Crow Girl. A former girlfriend of Eriksson’s is a psychotherapist and she and others read the authors’ manuscript to ensure plausibility and accuracy.

The first book in Sund’s trilogy was published in Sweden in 2010, and when I asked whether they were sick of talking about it, Eriksson and Sundquist turned to one another, sheepish, and nodded. “Honestly, yes. We’ve been talking about it for like six years,” Sundquist said, resigned to his admittedly very fortunate fate. He and Eriksson talk like people who know one another intimately, constantly looking to each other for confirmation of their words, completing each other’s thoughts and sometimes sentences, and providing the other with words in English. When I asked them how the novel came about, they told me they’d been traveling with Sundquist’s electropunk band, of which Eriksson was the producer, and the train trips could be up to 36 hours. A brief sample of how they talk:

Sundquist: “First of all we became very near friends, and we’re both very interested in literature and art and we talked a lot about that—”

Eriksson: “—and about what next to do because we started to get a bit old for rock and roll.”

S: “At the same time, seeing Stieg Larsson and his success—we were not thinking about success, but we read his books, and we liked them in some way, very simple, but he used the crime genre to tell important stuff.”

E: “Ideas. [To have] as many people as possible read it, and use the crime novel as a filter.”

S: “A platform. So in 2008, we both got divorced after very long relationships.”

E: “Everything falls apart in one or two months.”

S: “And I said okay, let’s write a book. And I started writing 40 or 50 pages, and I gave them to Jerker and I said, continue please.”

E: “I went out to my parents’—they have a small summer house out on a lake in Stockholm, there’s no electricity, no running water. And I wrote like 40 pages back.”

S: “And we said this is—”

E: “—two different things.”

S: “He has a more academic language, semicolons…”

E: “Håkan falls asleep in the middle of sentences.”

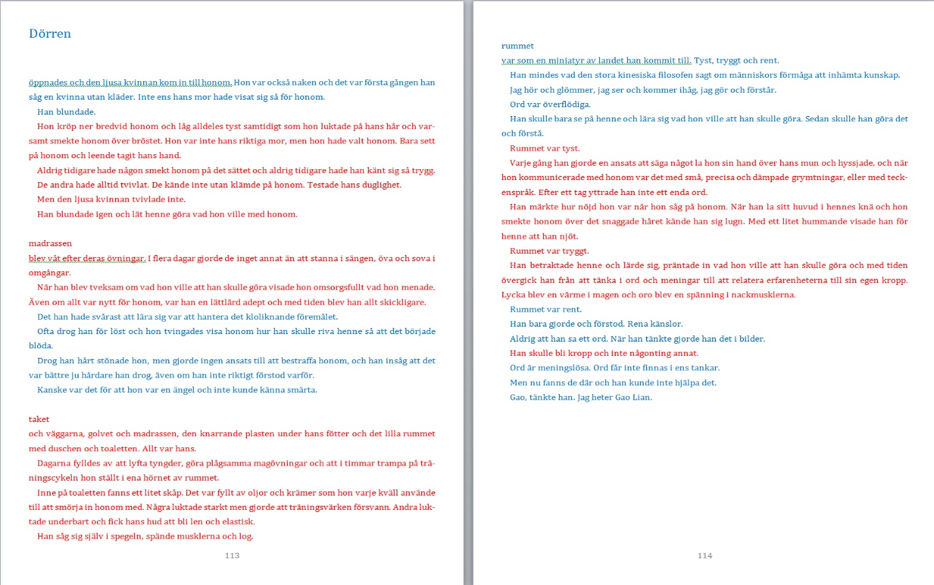

They now run an art gallery in Stockholm where they let artist friends and artists they admire hang and sell their work without taking commission; the back room of the gallery is their office, where they continue to write together (a standalone novel in Swedish came out last year, and they’re working on another now). They write like they talk, with Sundquist blaming his ADHD for his style—which Eriksson describes as “they go here, and then they go there, and then they die”—but which is a balance to Eriksson’s academic high-minded prose. They wrote the novel in four months—the whole whopping hundreds-of-pages-draft—together, in alternating colors, emailing a copy back and forth. They obliged me by sending pictures of the process:

The above isn’t all—there was also another color they would add in (green) for when they didn’t like something the other wrote. They’d only turn the text black once it was done. The process is bizarrely fitting for a novel dealing with, among other things, a person who has DPD, wherein multiple facets and voices are distinct from one another. Erik Axl Sund is like that character in a sense, and the two authors admit that it’s as if a “third person grew” between them; they don’t recognize what each of them wrote anymore.

* * *

The darkness of The Crow Girl, from child molestation to corruption and the failure to bring people to justice, came naturally to the authors, who revealed, a little cryptically, that they had experience with some matters in the book or knew people who had been through some of the horrors they describe. Sundquist commented that “it was a kind of therapy, writing,” and Eriksson added that “from the start, it was like Håkan was the patient and I was the doctor. Mental doctor. But after a while, I also got mental.”

It is difficult to imagine, having read the book only once rather than the dozens of times authors read their work, how anyone could dwell in the world of The Crow Girl for so long without going “mental.” From scenes describing a character named Victoria Bergman needing to make her father “happy” by sexually pleasing him to a stoic police officer finding herself unable to watch the screen on which child pornography that she’s investigating is being played out, the material is difficult. This is true too of some of Stieg Larsson’s work, which made me wonder, going into this interview, what on earth is happening in Sweden.

There seems to be a general feeling (at least among American liberals), that Scandinavia is a nearly perfect version of the democratic society, a place where the literacy rate is sky-high, where social services are excellent be it public education or universal healthcare, and where crime is shocking because it is rare. “We have been very good at supporting that image of ourselves,” Sundquist said, laughing, adding that “the Swedish king has said he doesn’t like Stieg Larsson because he’s making bad propaganda about Sweden.” Eriksson muttered that “the Swedish king should shut up, I think.” They say that this perfect Sweden I’m thinking of is that of the 1970s and ’80s, when they grew up, but that it isn’t what it’s like today, which is made clear in their writing.

Much of the overt social commentary in the book comes from the character Jeanette Kihlberg, a third generation police officer. In one scene, she tells a girl she’s interviewing, “Stockholm’s completely hopeless. It’s impossible to find somewhere to live if you’re not a millionaire.” The authors agreed that—before they became bestselling authors, anyway—they had the same issue with Stockholm, which is where everyone wants to be, a Swedish New York or San Francisco, but it’s impossible to be the bohemian artist type and manage it. Eriksson, when he first moved to Stockholm, sub-(sub-sub)-let 14 different apartments in four years. In another section of the book, when Kihlberg has been interviewing homeless children who congregate under a bridge, she leaves the scene disgusted, thinking, “Welfare state. Ha!”

Sweden has changed, and the nature of the immensely popular novels it’s producing—from Fredrik Backman’s socially critical though far more pastel-colored novels to Stieg Larsson’s books to, now, The Crow Girl—are an expression of this. “We wanted to write about things that scared us and make us angry,” Eriksson said, and added that around the time they started the book, a lot of “bad stuff,” as he put it, was happening. The authors told me about Göran Lindberg, who was arrested in January of 2010 and convicted of being a serial rapist—this is a police captain who had been hailed beforehand as “Captain Skirts” (the authors’ translation) because of his very public pro-feminist positions, when in fact he had been committing horrendous crimes the whole time. Eriksson is rendered speechless with anger as Sundquist fills in the details. Lindberg is already out of prison.

Another theme explored by the authors is the growth of child trafficking and covert immigration, and they chose to create a character using headlines for inspiration, specifically around the disappearance of Chinese children from immigration centers. I found a document on Wikileaks with the following summary, which reads more like the crime fiction of Sundquist and Eriksson than like a formal report:

Since November 2004, 120 Chinese children have disappeared from Swedish immigration centers. In all cases the children arrived in Stockholm via air from Beijing or Moscow, immediately asked for political asylum, and within days disappeared while their cases were pending. Swedish officials have yet to discover where the children end up, but investigative leads indicate onward destinations including Denmark, Germany, Italy, France and the Netherlands. Law enforcement authorities here believe a network of individuals in several European countries supports this traffic. A disheartening mix of legal “protections,” and apparent inadequate international cooperation, enables this phenomenon to continue. End Summary.

Arrival…Asylum…Disappearance

When I asked if they thought that human trafficking, molestation, sex crimes, and the other things they deal with are more common in Sweden than in other places, they said no, that it’s simply like the rest of Europe, the rest of the world: it’s not idyllic. Yet they do believe that Sweden is a safe place, safer than other places, and that crime novels with social concerns are a Swedish literary tradition going back to the ’60s, when Maj Sjowall and Per Wahloo, a married couple, started writing the Martin Beck detective series. But whereas they described those murder mysteries as cozy, The Crow Girl is anything but, because, as Eriksson said, “murder isn’t entertaining”—though Sundquist added, “it can be.” He admitted that there are some scenes they wrote to test the limits of their publishers, scenes they thought were too much, but that the editors didn’t question. But then a news item would come out about someone like Josef Fritzl, who kept his daughter in a sealed dungeon for 24 years. Nothing in the book, in other words, is really too much.

Nothing is too much, including the sexism portrayed. When we got on the topic of the novel’s female protagonists, and I asked why the two male authors wrote main characters who were women, Eriksson said, “Actually, we don’t understand how people can be surprised about it”—it being the idea that two men can write female characters faithfully. The most insulting question they were ever asked—a telling question that is a more extreme version of my own, in a way—was in Geneva, where a moderator asked if they wrote women in order to get laid. The answer was a resounding no, with Eriksson needing to almost physically restrain Sundquist, who was incensed. Most of their female friends, they said, have been sexually harassed, raped, or molested, a truth that will likely resonate with many readers. As a response, most of the men they’ve written into the book are assholes (the authors’ word). Kihlberg’s character was originally supposed to be the one “okay” man, but after 300 pages of writing, they decided to make the character a woman, because for one thing, it upended gender stereotypes and it made the character more interesting—she just worked better as a woman, one who’s constantly fighting the system she works in, in which her law enforcement superiors doubt her abilities and pass her over for promotions. In other words, she allowed the authors to explore another social issue that angers them, sexism in the workplace, and in such an important workplace, no less. “Gender is a social construct,” Sundquist stated—we fistbumped over this—but it’s a construct the authors know is very much in play in their book, where early on in the story a convicted child molester waxes philosophical about the innocence of childhood, a time when children are neither male nor female because they haven’t hit puberty yet.

Whenever the discussion turned to pedophilia and child molestation, which is a big part of the novel, the authors became visibly disgusted. It seems entirely possible that a true third person materializes between them when they write, one who is capable of dealing with these dark subjects with detachment. Or perhaps the two were simply far enough away from their writing selves to regain their non-“mental” ability to feel. It was a relief to see that Erik Axl Sund was two emotionally astute, middle-aged punk-rockers in black clothing, behind sunglasses, with cigarettes in hand, rather than one truly cold bastard.

Ilana Masad

Ilana Masad is a writer of fiction, nonfiction, and criticism whose work has been widely published. Masad is the author of the novel All My Mother's Lovers and is co-editing the forthcoming anthology Here For All the Reasons: #BachelorNation on Why We Watch.