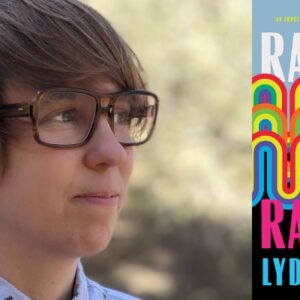

Encounters with a Mad King: Jac Jemc on Finding a Story While Lost in Research

“I needed to know everything so I could carefully carve out the something I wanted the book to be about.”

Everyone warned me to limit my research. I heard them, and said, “Oh, I know! It’s all too interesting! Very dangerous!” But I also have that contrary side of my personality that privately thought, “Sure, but they don’t understand my project and my position.”

While writing my novel Empty Theatre, I quickly learned that historical fiction is supposed to primarily be interested in telling the human story behind historical figures and events. To achieve this, every well-intentioned article and essay touted a similar line of advice: Avoid over-researching so you can focus on the story. Write the story and then figure out what you need to know afterwards. A little goes a long way. The process could go on forever if you don’t cut yourself off.

But, I argued,—with those generous historical fiction writers who’d gone before? with myself?—what if molding the lives of my historical figures into a recognizable novel shape would just be reinforcing the ways in which history had gotten those figures all wrong for 150-plus years? What if a novel could instead examine the tessellated moments of acute pain and bright joy and aim to tell a truer, more beautiful because more complex, version of the lives that history has coated with its oversimplifying glaze?

The idea for my novel was born after visiting “Mad” King Ludwig II of Bavaria’s most well-known castle Neuschwanstein on vacation. I was charmed by the facts that get passed around about him most often: 1) He was the primary patron of Richard Wagner’s operas, 2) He built castles that looked more like stage sets for fairytales than working palaces of the time, 3) He was gay and official records had tried for a long time to cover that fact up, and 4) His statesmen had him declared insane by a doctor who had never met him and removed him from the throne, but no one seems to have a clear understanding of why both Ludwig and his doctor were found drowned outside of his Castle Berg the following day. That was enough for me. I was hooked. I wanted to know everything.

I am not a person who is generally interested in royalty. I tried to care about the Harry and Megan drama and gave up a few minutes into the documentary. If I see a book with a crowned figure on it, I tend to avoid it. So I was as surprised as anyone that I found myself wondering about the possibility of writing a novel around what I’d heard.

I ordered a book about Ludwig, and then I ordered all of the books about Ludwig I could find. I started transforming the shiniest and most prickly moments into scenes, while I continued to read more books by and about the peripheral figures in his life: Lola Montez, Richard and Cosima Wagner, Empress Sisi of Austria, Otto von Bismarck, Elisabet Ney and her husband scientist Edmund Montgomery, Prince Rudolf, Friedrich Nietzsche, Heinrich Heine.

I read the books they read and went to the opera for the first time. I researched the palaces and their dynastic family histories. I applied for a fellowship in a small town in Southern Germany for seven weeks and received it. I spent weekends traveling the region, visiting all of Ludwig’s castles in Bavaria, and then all of Sisi’s palaces in Austria and Hungary, and then all of the sites associated with Wagner in Bayreuth. I took copious notes. I tried to teach myself German. Back in the states I went to Elisabet Ney’s studio in Austin and then I scheduled a group tour of her farmhouse in Hempstead, but let the guide know the group I’d booked would be only me.

A young woman in a corset and a hoop skirt led me through the two-story home. I tried to tell her she could just wear her regular clothes so she could be more comfortable, but she said the costume helped her get into character. At various points she asked if we could sit down so she could catch her breath.

What if a novel could instead…tell a truer, more beautiful because more complex, version of the lives that history has coated with its oversimplifying glaze?I wrote over a thousand pages, close to 300,000 words, of a first draft, including everything that interested me and seemed relevant. But here we had two historical figures—Ludwig and Sisi—who were more than a little extra. If anyone deserved a draft that was a little overmuch, it would be them. I liked the idea of being a woman who was allowed to write a book that long, but I knew it couldn’t last. I knew I needed all that research to overpower my impostor syndrome and convince myself that I knew what I was talking about. I needed to know everything so I could carefully carve out the something I wanted the book to be about. I’d done what everyone told me not to do.

I had written storylines that spanned the entire novel for Lola Montez and Elisabet Ney, delivering both of them to an America they hoped would allow them to achieve their goals beyond the limitations of Old Europe, but the States ultimately proved equally stifling. In the end, the connections between these figures and Ludwig and Sisi ultimately weakened what I was trying to explore though in terms of the challenge of living up to expectations, because Montez and Ney were the only ones expecting anything of themselves. They had to go.

I am not a fast writer, but I am consistent in my practice. I average about seven years a novel now, but that doesn’t trouble me. Instead, the length of the process has helped me see that the decision to work on a specific novel is a decision about how I’d like to spend the next stretch of my life: what I want to learn about and what I want to think about. This decision is largely intuitive—guided by what obsesses me in a given moment. I write and I try not to wonder why until a bit later.

People ask if it’s easier to write a novel now that I’ve already done it a couple times, and my answer is that the only reason it’s easier is precisely because I’ve done it before—I’ve followed those quiet, inexplicable voices nudging me on and suggesting where I turn and when to stop—and so, if it’s worked before, there’s no reason it shouldn’t work again.

Looking back, I realize I was eager to fall down a research rabbit hole. I wanted a new vocabulary of time, space and image. I went deep willingly and happily. I loved the experience of it. I am so grateful to have spent all that time, with those materials, trying to determine who those people were in all their knotty glory, without oversimplifying them. I needed that time to figure out how to write that story in a way that felt both true to them and true to me.

Did I lose time learning about things that didn’t end up in the book? The book is a third of the size it once was, but I don’t see any of that time as wasted. My advice to you? Research as much as you want to. Yes, you’re writing a book, but you’re also living a life. Take all the time you need.

__________________________________

Empty Theatre by Jac Jemc is available from MCD Books, an imprint of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, a division of Macmillan, Inc.