An Afternoon with an Elite Palestinian Family in Jerusalem

Lis Harris on Three Generations of Israeli Life

Over the years, as we drove between the neighborhoods of Niveen Abuleil’s family and Ruth HaCohen’s family (and around Israel), Fuad Abu Awwad and I logged hundreds of miles together. I learned fairly soon that though he was no snob, he was keenly aware of status and had an old-fashioned respect for educators. No amount of cajoling, even with the passage of time, would persuade him to call me, in the American way, by my first name.

Instead, he insisted on calling me Doctor, emphasis on the second syllable, because I teach at a university. When, helping me with my luggage one day, he saw that the approach to my pocket-size studio was via a dim, labyrinthine garage with a certain resemblance to the mob rubout site in the film Some Like It Hot, he made it clear that he didn’t consider my housing arrangement suitable.

There seemed to be few people in Jerusalem Fuad didn’t know or at least know about. Customarily, one of the names parents are given in that part of the world, called a kunya, incorporates the name of their oldest son (as in Abu Mazin, or “father of Mazin,” for Mahmoud Abbas, and Umm Mazin, or “mother of Mazin,” for his wife). People are identified not so much for what they do or who they are as by who their parents are, and Fuad had apparently committed to memory the life stories of a prodigious number of them.

Before I met the Abuleils, I had been meeting for several years with another family who were among the ayan, or elite families of the city that have traditionally dominated life there. That family had been part of the city’s power structure since the 12th century, and fellaheen, or farming families, like the Abuleils were no part of their experience, though they would sometimes dutifully extol them for their traditional ways and perseverance.

That family and I parted company because of a messy divorce a key couple in the family was going through, a struggle that transformed the family saga into too much of a telenovela. By then I had been writing about them for more than three years, so it took me a while to decide to move on, but when I told Fuad what had happened, he wasn’t too surprised, as he believed, along with F. Scott Fitzgerald, that the rich were different from you and me and consequently behaved in unconventional ways.

Fuad was also familiar in a broad way with the histories of nearly all the families I began contacting next. By then, the first Gaza War (2008–2009), called by the Israelis “Operation Cast Lead,” had taken place, with its heavy death toll and massive destruction of the territory’s infrastructure. Most of the Palestinians I spoke with were more disgusted than usual with what they considered the Western nations’ indifference to their fate and were in no mood to talk with outsiders like me.

Young professionals were particularly unwilling to participate in a venture they thought might get them in trouble with the Israeli authorities, even when their parents were game. One entire fruitless summer went by and half of another, with Fuad correctly understanding, from my forlorn expression when he pulled up in front of yet another East Jerusalem home to drive me back to my own, that I’d failed in my quest yet again.

Then one afternoon, to my astonishment, he announced that he’d phoned Nasser Eddin Nashashibi on my behalf, for help. A member of one of Jerusalem’s oldest and most prominent patrician families, Nashashibi was a journalist who had also served as secretary to the Palestinian delegation to the Arab League in 1945 and another time as the league’s roving ambassador, as director general of the Jordanian Broadcast Service, and as a contributing editor to the popular Egyptian weekly Al-Ahram. Members of his family had held high positions under the Mamluks, Ottomans, and British. Nashashibi lived in a huge villa in the East Jerusalem neighborhood of Sheikh Jarrah and owned retreats in London and Geneva.

Perhaps centuries of familiarity with the custom of having elites like the Nashashibis solve local problems played some role in Fuad’s decision to contact him. Fuad certainly hadn’t met him or known anyone who had, but, convinced that I could use the advice of someone connected to a lot of people in the city, he proceeded to ignore the social taboos bred into his bones and rang him up. This was more or less equivalent to your local yellow cab driver phoning one of the Rockefellers, but Fuad, contrary to everything I knew about him, made light of it, and, wonder of wonders, Nashashibi had agreed to see me that very day! What a generous man, I thought, and what openness to a fellow Arab!

An elegantly dressed older woman led me into a soaringly high ceilinged room, and Nashashibi, who was then 88, apologized for not standing. He had stayed up too late the night before, he said, and was tired. He didn’t look his age. He had carefully groomed silver hair, was wearing a burgundy silk dressing gown, and had a fleshy face, a strong nose, and, despite his fatigue, a booming and rather commanding voice.

Surrounding him were hundreds, perhaps thousands of mementos from his long career: photos of himself with presidents and sheikhs, beautiful women in elegant gowns, beaming celebrities of various nationalities, diplomats, and relatives, all in silver frames; a virtual warehouse of elaborately carved antique tables and chairs; and a desk covered with unstable-looking piles of paper and numerous brass trays piled high with paperweights, letter openers, and other bibelots too numerous to mention. With Nashashibi at the center of all this, the effect was akin to seeing a faded, slightly damaged portrait within an ornate, jewel-encrusted frame.

Most of the Palestinians I spoke with were more disgusted than usual with what they considered the Western nations’ indifference to their fate.As it turned out, he had neither advice of any kind nor a single thought about my dilemma. He looked bored and was quick to change the subject, when I briefly brought it up, to one he very much did want to talk about: his uncle, Ragheb Nashashibi, a moderate Palestinian politician and longtime (1920–1934) mayor of Jerusalem, about whom he had written a biography that had been published 15 years earlier. “Storrs [the British military governor of Jerusalem at the time] called my uncle ‘the ablest Arab in Palestine,’ and he was,” Nashashibi said. In his uncle’s era, there were two main political factions, one led by his uncle, the other by Haj Amin al-Husseini.

Both men opposed the Zionist project, but, as portrayed by his nephew, his uncle believed in negotiated efforts and artful persuasion, which he hoped would eventually succeed in moving the British to reject the Jewish homeland idea and support the handover of the institutions of government to the country’s rightful indigenous leaders. Unlike many references to his uncle, which tend to characterize him as over-conciliatory and ineffective, the word “moderate” is generously applied by his nephew throughout the text, and the broad picture is of someone humane, clever, and diplomatically skilled.

His uncle’s rival Husseini is portrayed in Nashashibi’s book as a fervent nationalist and an uncompromising zealot who sometimes expressed his displeasure with those who held opposing points of view, like Ghada Karmi’s uncle, a father of eight, by assassinating them. The book offers a stout defense of his uncle but leaves out a reality that over time had a far more malign effect on the progress of the Palestinian people than the rivalries of the two major political factions—that Nashashibi and Husseini were both cleverly manipulated by the British.

Husseini, no less than Nashashibi, despite his inflammatory rhetoric, was for a time extremely obsequious toward his British overlords, who appointed both men to their positions, sustained them financially, and made it possible for Husseini to gain the power he did—power that eventually gave him standing when he became the premier anti-British, anti-Zionist nationalist leader. In general both factions tended to negotiate politely, even fawningly, with the British privately, while showily denouncing their policies in public.

Nonetheless, for more than a decade and a half, both men appear to have been unaware that they were being used as pawns in the familiar British colonial strategy of distributing favor and patronage to discourage rebellion and sowing dissention among leaders so they were unlikely to remain unified in their desire for self-determination.

After many hours of excavating the vagaries of old Jerusalem political cabals, during which I fell into a kind of stupor, Nashashibi suddenly sprang to life. He’d just had an idea that he thought was inspired, he said, though somehow the studied way he said it made it clear that he’d planned to say this all along. “My chauffeur quit last week and I have no one who can drive me around. Do you think that, um . . . Fuad might like to be my driver?”

“Well, I don’t know. . . . Why don’t you ask him?” I said, handing him my cell phone after calling Fuad, who had just driven up outside the villa’s electronically controlled gate. They subsequently arranged for Fuad to drive him somewhere the next day. I thanked him, and we took our leave. Fuad had a thoughtful expression as we drove along the busy highway linking East and West Jerusalem.

His wife, Kivo, had recently lost her job when the medical supply company she worked for underwent a downsizing spasm. Nashashibi was clearly a very rich man, and Fuad allowed himself to imagine a plummy sort of sinecure, one that might even replace his current job with its long, exhausting hours.

But some days later a downcast Fuad let me know that the whole venture had turned into a disaster. Apparently the old man had asked Fuad to drive him around for several days and required him as well to transport the older woman who’d shown me into the living room (and whom he later introduced as his niece) for several hours as well. Neither of them could be coaxed at any point to discuss money, and the woman even seemed irritated when Fuad brought the subject up.

“Look, I have a wife and three children. I have to know that I can take care of them,” Fuad told me he’d finally said to Nashashibi.

It then emerged that the job would additionally entail traveling with Nashashibi to London and Geneva when he visited his residences in those cities, and where Fuad would be expected to more or less always be available, and the salary offered was laughable. Fuad told me he had shaken his head in disbelief and was about to decline the offer but never got a chance to.

At that point, Nashashibi had ended the conversation abruptly, saying he wouldn’t be requiring his services any longer. And that was the end of Fuad’s cross-class caper and liveried fantasies. “Oh, and by the way, what do you think they paid me for all that driving around?” he asked a few days later, when he had arrived at the point where he could laugh at his experience.

“Nothing, can you believe it, zero, not a single shekel!”

__________________________________

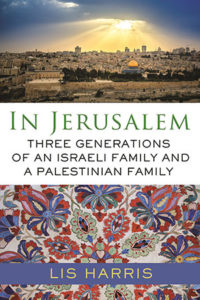

Excerpted from In Jerusalem: Three Generations of an Israeli and a Palestinian Family by Lis Harris. Copyright 2019. Excerpted with permission by Beacon Press.