Elyse Durham on Depicting the Artistic Side of the Cold War in Fiction

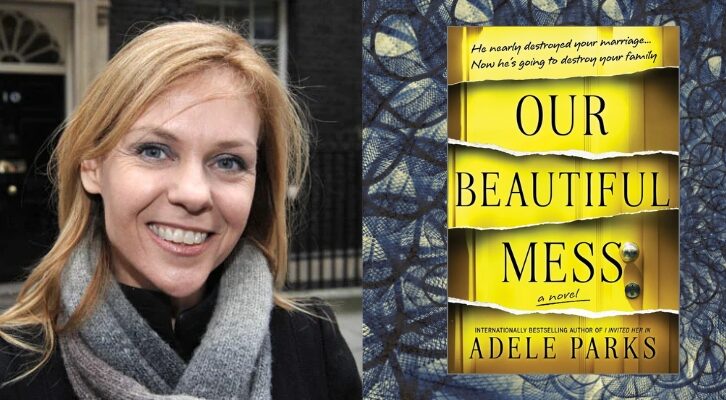

Jane Ciabattari Talks to the Author of “Maya & Natasha”

Elyse Durham’s immersive and thematically timely first novel centers on twin sisters, born during the Siege of Leningrad, trained as ballet dancers at the celebrated Vaganova, and launching their careers at the height of the Cold War. The plot is set to detonate at a critical point in the Cold War, the year 1962, when the Cuban missile crisis has the world on tenterhooks while a cultural exchange between defector George Balanchine’s New York City Ballet and the Soviet Bolshoi is in progress, and the Russians are filming their version of War and Peace, which went on to win the 1968 Oscar for best foreign film.

What drew Durham to write about the competitive and magnetic ballet universe? “I fell in love with ballet as an adult, and it transformed my relationship with the physical world: it reminded me that being an incarnate creature is a privilege,” Durham explains. “This book is personal inasmuch as it reflects that transformation.”

“I’d grown up around dancers—sometimes I’d try on my sister’s pointe shoes when nobody was looking—but ballet never really held any interest for me until 2014, when I stumbled upon the work of New York City Ballet choreographer Justin Peck, specifically his collaborations with indie musician Sufjan Stevens. Those ballets astonished me so much that, from then on, I became insatiable for dance. It was like If You Give a Mouse a Cookie: watching ballet made me want to try it for myself at the barre, and trying it for myself made me want to learn about it, and learning about it made me want to write a novel.

“My interest in Russian history dovetailed organically out of that experience: reading about dance history—and Jennifer Homan’s book Apollo’s Angels in particular—piqued my interest in Soviet dancers, especially the ones who defected. I wondered what it would be like to leave everything behind and suddenly be immersed in this entirely new culture, knowing you could never go back. And it intrigued me that, during the Cold War, both the United States and the Soviet Union used artists to exert soft power—and that the artists themselves often had mixed feelings about this.”

*

Jane Ciabattari: How did you develop the characters of the twins, Maya and Natasha, who are inseparable during their early years, and then face a shattering betrayal? How were you able to make each with a unique personality, despite their parallel paths?

We’re all shaped by our eras…so at every turn, I asked myself how the historic events I was studying affected my characters’ daily lives and points of view.

Elyse Durham: Maya and Natasha’s formative experience is being abandoned by their mother: their individual responses to this shape who they are. Natasha decides she’s not going to rely on anybody ever again, and she prioritizes everything around having the freedom to do and be what she wants. Maya internalizes the loss: she wonders if their mother left because there’s something wrong with her, and this makes her very clingy and dependent. Which, of course, sets up a tension between them: the more Maya clings to Natasha, the more Natasha wants to pull away.

I also decided to give the girls different strengths as dancers, each inspired by real-life ballerinas I admired. Natasha’s ebullient and quick, like New York City Ballet’s brilliant Tiler Peck, who’s been a hero of mine for many years. Maya, once she comes into her own and begins to embrace her strengths as a dancer, thrives in adagio, like City Ballet dancer Sara Mearns. I’ll never forget seeing Sara dance during NYCB’s first performance after the pandemic. Sara entered the stage at the beginning of the second movement of Symphony in C and a hush fell over the entire audience. We were all spellbound. After those lonely years of lockdown, it was such a moving experience to be part of a crowd of several thousand people, all entranced by the same thing at the same time. I watched Sara sweep down the stage en pointe, so majestic, everyone just wrapped around her finger. I thought, There she is. That’s Maya.

JC: What was your process for weaving real historic background into this personal story of family and passion and ambition?

ED: The story really emerged from the history. It wasn’t, “Oh, I want to write a book about ballet, so let me learn about it.” I’d been studying and researching ballet and the Cold War for several years before I even realized I was working on a novel.

It took me a long time to decide what era of Soviet history to make my focus—at one point, the book began with the Revolution and ended with the Soviet government collapsing—but I became intrigued by this midcentury period in Soviet history known as the Thaw. I wanted to know what it felt like to come of age at this time when you had more cultural freedom than in previous generations, only to have it come crashing down again in adulthood. We’re all shaped by our eras—each of us is the product of the pandemic and these interminable Trump years—so at every turn, I asked myself how the historic events I was studying affected my characters’ daily lives and points of view. That helped keep me from getting lost in the weeds, because I’m so fascinated by history that I wanted to include every single interesting detail—but that book would have been several thousand pages long…

JC: Among the “real” characters in this book, you include Presidents JFK and Khruschev during the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. What research was involved in portraying these two at a near-fatal moment, and tying in the Kirov, which was touring in the U.S. at the time, and New York City Ballet, performing in Moscow? (You note it was the Bolshoi, not the Kirov, that toured America that year; why the change?)

I also interviewed cultural historians to get a sense of what the crisis was like for people on both sides. I drew charts and maps to keep track of all the moving pieces. My husband introduced me to Twilight Struggle, this six-hour board game about the Cold War. One person plays as the Soviet Union and the other as the United States, and you’re trying to keep DEFCON levels low as all the events of the Cold War unfold around the world. That really opened my eyes to the Cold War’s scale and scope.

The moment I realized all of my story’s elements—Soviet ballet, George Balanchine, the filming of War and Peace—came together during the Cuban Missile Crisis, the book really gelled. It’s a moment I remember vividly. That City Ballet and the Bolshoi were both touring abroad when the Crisis happened—and that War and Peace was in the middle of filming—was such a perfect climax that I never could have invented myself. I think I gasped at my desk. Being a novelist requires having many astonishing bouts of good fortune.

As to swapping out the Bolshoi for the Kirov—that was done to streamline the story and make a character’s motivations more clear at a crucial moment of decision. The Vaganova, where Maya and Natasha study, is also a feeder school for the Kirov, so it made sense to have that be their destination of choice.

JC: What research was involved in giving such a detailed portrait of George Balanchine and his New York City Ballet colleagues Lincoln Kirstein, Jacques d’Amboise, Nora Kaye, Betty Cage and Tanaquil Le Clerq, his wife at the time?

ED: I did all the things you’d expect: reading every book I could find about Balanchine or by people who knew him (Jennifer Homans’ histories were key here, too), watching untold documentaries, listening to interviews. All of these things helped me understand the culture of City Ballet and the relationships Balanchine had with his colleagues, too. But I also got to know him through his work. Though I was a broke grad student, I took these marvelous trips where I’d scrape together enough money to stay in the city for three or four days and go to the ballet every single night, which sometimes meant seeing Serenade three nights in a row. Even standing in the Koch Theater felt like getting to know him, because he supervised the construction himself (and had very strong opinions about its design!).

A delightful surprise during all of this was learning that like me, Balanchine was an Orthodox Christian. (Catholics can throw a rock in any direction and hit another Catholic artist, but us Orthodox aren’t quite so lucky.) Granted, it doesn’t appear he practiced his faith much—like many of the people in our communities, he connected most strongly with the feast days and food—but there’s something in his work that seems unmistakably Orthodox to me. Many of his ballets have this sense of holiness, as if he’s trying to express the glory of being an incarnate creature. The doctrine of the incarnation—that God became flesh—is incredibly important in Orthodox theology. It makes perfect sense to me that one of the greatest Orthodox artists would be a choreographer.

JC: How did you first learn of Yekaterina Furtseva, who was the Soviet minister of culture who oversaw the New York City Ballet’s Soviet tour and the filming of War and Peace, a Soviet competitor to the U.S. version starring Audrey Hepburn? How did you learn about the challenges Furtseva faced?

ED: Yekaterina Furtseva is kind of like the Forrest Gump of the Thaw: look at any significant cultural event in Russia in that decade and there she is, usually trying to solve fourteen problems at once (like in the middle of Maya & Natasha, when she’s trying to track down several dozen bolshoi for Sergei Bondarchuk). She’s both formidable and perpetually on the verge of being exasperated, which made her very fun to write. She appeared over and over in my research about Soviet ballet, and when I realized she was involved in War and Peace too I got really excited, because that meant she could help span Maya and Natasha’s separate worlds.

JC: In one scene Furtseva is with Khruschev when he visits a museum exhibit in 1962, finds a painting offensive and declares a new Soviet policy against obscenity. At what point did you see how this could work into the novel, creating a crucial plot twist?

ED: Furtseva actually isn’t in that scene—Khrushchev visits the art exhibit and then gives her an earful about it later. But that incident—which is known as the Manege Affair—was a huge turning point in Soviet culture. In a way, it was the beginning of the end of the cultural Thaw, and it had immediate and far-reaching consequences for Soviet artists, as Maya & Natasha explores. So it was a natural way for me to unpack the struggles Maya and Natasha face as they reach adulthood, and this relatively stable period they’ve grown up in is coming to a close—and shifting everything along with it.

But the other reason I had to include it in the book was that I found it hilarious. A leader of a world superpower loses his mind over nudes in an art gallery—not just because he found the style too avant-garde, but because he was deeply offended by the subject matter (which, by the way, was akin to anything you’d find in a contemporary art wing). Khrushchev had a knack for memorable turns of phrase, and some of the things he yelled that day ended up in my scene verbatim. He asked one artist if his painting had been “daubed by the tail of an ass.” What’s not to love about that?

JC: How did you research the filming of the Soviet War and Peace—the director Sergei Bondarchuk and Irina Bondarchuk, his dancer wife; Lyudmila Savelyeva and Vayacheslav Tikhonov, the actors who portrayed Natasha and Lev? And the scenes in which Natasha visits the U.S. when War and Peace wins an Academy Award for best foreign film in 1968?

What gets lost in those kinds of stories are the actual people who lived through these eras. They weren’t automatons: they were real people.

ED: My fascination with Bondarchuk’s War and Peace began with seeing the entire seven-hour film, fully restored, at the Detroit Film Theater in the Detroit Institute of Arts in 2019. It was one of those dramatic before-and-after moments in my life: at that point, I’d been working on the novel for a few years, but the scale and grandeur of that film totally transformed the way I’d been thinking about Soviet art. The state poured millions upon millions of dollars into this movie, and it shows. (It’s also an incredibly moving and human film, both deeply faithful to Tolstoy and an amazing art object in its own right—one of those I’m-so-glad-I-was-born-so-I-could-see-this kinds of experiences.)

This is another place where good fortune benefited this novel: right as I started writing about War and Peace, the Criterion Collection DVD came out, with all kinds of incredible behind-the-scenes footage and documentaries. I got so many details from these documentaries—like that, when filming the grand ball scene, Sergei Bondarchuk waved scarves in front of the camera so it would feel like the viewer was being grazed by ballgowns. (That’s also where I learned that the cinematographer was on roller skates for that scene!) Film historian Denise Youngblood, an expert on Soviet cinema, was a crucial resource, too, and she was so generous with her time. I can’t tell you how many people went out of their way to be helpful and kind to me while I wrote this novel.

Researching Natasha’s trip to the Academy Awards was really fun. I watched a lot of footage from the Awards themselves—it was the same year that Barbra Streisand wore that see-through jumpsuit that scandalized everybody—and I had to do a lot of digging through historical records for tiny details about Natasha’s travels. At one point, I was hunched over a completely indecipherable Pan Am flight timetable from 1968, trying to figure out how long it would have taken her to fly from LA to New York. Thankfully, my husband, who’s good with numbers, came to the rescue and helped me figure it out!

JC: You continuously insert details about the Soviet surveillance system and fear-driven obedience common in the Soviet Union during these decades—societal norms that lead to Maya and Natasha and other talented dancers having fantasies about American freedom and abundance, and in some case to defections, including Balanchine’s. You write beautifully of the pain of exile. How did you develop this overview of Cold War Soviet life?

ED: Thank you so much for that kind compliment. You’re right that I included those details—but, from the beginning, I also had a strong desire to push against American stereotypes about the Soviet Union. A lot of pop culture depictions of Soviet culture are so one-sided and stilted that they feel like propaganda themselves. What gets lost in those kinds of stories are the actual people who lived through these eras. They weren’t automatons: they were real people, with things they hoped for and strongly-held opinions about ordinary things.

One of the most important moments in all my research was at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, when I was sifting through Mikhail Baryshnikov’s personal archive. I was watching this film of two Muscovite dance students practicing a duet when, suddenly, the girl slipped and fell. She immediately started laughing. It’s the opposite of what you’d expect: advanced arts students are always under serious pressure, especially in the Soviet Union—but for all that, she was still just a girl. If she could find humor in her situation, it seemed essential that I did, too.

All that said, many Soviet young people had very romantic ideas about the West, and some left everything behind to come here. They came for different reasons—hoping for a better life, more artistic freedom. Many of them, for the rest of their lives, experienced doubt over whether they’d done the right thing, even when they were grateful for their new lives. To leave a country, your home, in a way that means you’ll never return—I can never know how that feels. But I did leave the religious tradition and culture I grew up in—I was raised in the conservative evangelical community, which I left as a young adult—so I know something about the pain of self-exile. It’s a complicated pain. Even if you know you made the right call, even if you’re grateful for where you ended up, being an expatriate is isolating.

JC: What are you working on now/next?

ED: I’m one of those people who always has a bunch of projects going on at once. I don’t know which one’s going to pull toward the finish line first, but I can tell you that I’m always drawn to projects that require me to completely immerse myself in something new. It just wouldn’t be fun for me otherwise.

__________________________________

Maya & Natasha by Elyse Durham is available from Mariner Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.