Elizabeth Ellen on Small Presses, Autofiction, and Reading the Uncomfortable

“I look for a gut punch. I look for unexpectedness.”

For Elizabeth Ellen, April was a banner month. The press she runs, Short Flight/Long Drive, just released five new books, two of which are Ellen’s. The first, Her Lesser Work, is a collection of mordant and formally inventive stories circling themes of, let’s say, desire and escape within repressive structures; the second, Exit, Carefully, a family drama in playscript form. As both a writer and editor-publisher of indie giants like Tao Lin and Garielle Lutz, Ellen is responsible for some of today’s most exciting, emotionally truthful, morally knotty work. Below, Ellen answers a few questions over email about both her new books and her experience helming a small press.

*

Walker Caplan: I was so glad to be able to read the new drop of SF/LD books, which are all killer. What do you look for in an SF/LD book?

Elizabeth Ellen: Thank you so much! I look for a gut punch. I look for unexpectedness—either sentences or characters or activity; all of the above. I look for words I’ve never read before, scenarios I haven’t yet envisioned, people I haven’t met. I look for outcasts, renegades, rebels, rulebreakers. (I get bored easily.)

WC: You founded SF/LD in 2006. Have the operations of SF/LD changed at all since its founding? What are some of the challenges you’ve faced running an indie press?

EE: I don’t think much has changed. It’s still basically one person doing everything—or, I do everything with the lessening but still quite necessary and ever-appreciated help of Aaron Burch: thank you, Aaron! Probably the biggest challenge running SF/LD has been my instinct to burn bridges and my inability to network/ask for help/figure out “publicity.” My fierce desire to remain independent definitely doesn’t make anything easier and certainly prohibits some broadening of our audience. I try to warn potential authors of this up front and often. Word of mouth is extremely important for all small presses, but ours even more so.

WC: Did you always imagine putting out Her Lesser Work and Exit, Carefully on SF/LD?

EE: Exit, yes. Her Lesser Work, no. Exit I wouldn’t have had the first clue where to send, how to go about publishing. I’d never written a play, my agent had zero interest. I just wanted to write it. Beyond that I had no real motivation. Or, I had a fantasy, of course, of it one day being performed. But that fantasy felt about as real as going back in time and hanging out with Bret Easton Ellis, Donna Tartt and Jay McInerney and becoming one of the Brat Pack.

As for Her Lesser Work, I had an agent until recently who was dutifully sending out many of the stories contained within that collection. Originally I think we both assumed at some point she would send the collection “out.” But as time went on, the stories I wrote were weirder and weirder and didn’t exactly seem to fit a book that would be bought by a larger publishing house, or even a medium one. So we agreed to part ways. And yet again I found myself as my own editor, publisher, and publicist. This was never my intention for Saul Stories or Person/a or Her Lesser Work. Like most writers, I intended and desired someone else to publish them, publish me. But not at any cost. And always the cost has become too much for my level of comfort with my control over my art. My, my, my. Lol. Character flaws showing!

WC: Moving to your new books: the first story in Her Lesser Work features a benign encounter between an orangutan family which inspires disgust and fascination in the human onlookers, who read it as sexual. It reads as a kind of thesis for the collection, or at least one element of it: you deal with topics that audiences often sensationalize—female sexuality, incest, violence—without top-down moral judgment. What draws you to, or how do you approach, writing about these moments?

EE: I think I just try to look at every interaction or action or action or person from multiple sides, multiple viewpoints, to try not to allow myself to simplify people or their actions, but to look at them as complex individuals, as actions, as complexities, which is the way I view myself and the choices I’ve made, or not made, in my life.

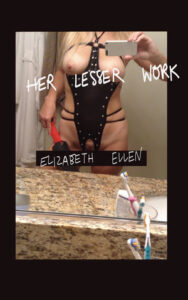

WC: Speaking of things people might sensationalize: Her Lesser Work’s striking cover, which might limit its book-Instagram publicity. How’d you arrive at this cover? What does it tell a reader?

EE: I think it might tell a reader: this bitch is crazy! I actually surprisingly didn’t put that much thought into the cover, but now that I’ve been asked about it a couple times I guess I might say: if you’re uncomfortable with the cover, with the human body (or, as my mother and I were viewing it: with an unapologetic woman), you might be uncomfortable with some of the stories told within or the way in which they are told, as you pointed out, less with moral judgment and more with a complex view that is more wanting to understand or merely to display than to judge, this book might not be for you.

P.S. One of my friends put it on her Instagram a week ago and it’s still there. :)

I try to look at every interaction or action or action or person from multiple sides, multiple viewpoints, to try not to allow myself to simplify people or their actions, but to look at them as complex individuals, as actions, as complexities.

WC: In “She Lit Cigarettes Instead of Talking,” the narrator laments how readers wrongly infer her personal life from her writing, and in “YOLO,” the narrator says, “[A writer] always reveals what you, the reader, want her to, what you believe is your right.” I’m interested in how you play with and acknowledge the reader’s relationship to writer, and would love to hear you talk about it a little. If “a fiction is not a suicide note. Nor is it a call to action. Nor is it a cry for help,” what is it? One of your stories zooms out from third to first person to include the voice of the writer, and the daughter in your play is named Elizabeth Ellen. Do you view these stories as “truthful” or autofictional in nature at all, or are you just playing with readers’ assumptions even more?

EE: I think a fiction is probably all of the above, and in stating what something isn’t, we are inferring what it is also. That’s probably a little trick, a tell. But I think ultimately only the author knows what is real and what isn’t, what is fiction and what is non-. Like a good magician. And a magician never reveals her secrets. Or how the trick works.

My only problem with the term “autofiction” or when friends say, “Oh, I recognize something in this story; therefore it is nonfiction” is it’s a lazy way of looking at art and it also dismisses the art. It’s like when we are very young and look at a Pollock painting and say, “I could do that.” Oh, really? Okay. Do it then.

WC: I won’t! In “YOLO,” the narrator belongs to a book club with rigid rules: “no books written by straight, white men,” “no thrillers in which a woman dies.” The narrator “[thinks] this type of idealism small and meaningless.” Do you find this type of idealism meaningless? Or, do you think principles like this are ever useful?

EE: I think rules are dumb (read: limiting), though maybe conceived of for worthy reasons. I think awareness of an individual’s or a group’s weaknesses and tendencies is worthy of exploration and worthy of conversation. I think reading what makes us uncomfortable—a thriller in which a woman dies, perhaps—can lead to great discussions, less discomfort. I was asked in book club how I handled problematic books (Roald Dahl was given as an example) when my daughter was young, how I vetted them, and I said I never vetted, we had conversations.

Every problematic book or paragraph or piece of art or movie is a wonderful conversation-starter. If you vet, you never have the important conversation. If you limit what or who you’re reading with rules, you’re basically overcorrecting, becoming prejudiced, biased in the opposite manner. “Now we refuse to learn anything about the male straight white experience in the current moment.” That doesn’t seem helpful or useful, either. A book club is an odd animal. There can be a lot of . . . proclamations made in order to gain popularity in the group, because, of course, who doesn’t like to be liked?

A good magician never reveals her secrets. Or how the trick works.

But, ultimately, the goal of expanding one’s reading experience, by reading authors of different races, religions, sexual orientations, genders, countries of origin, is admirable and useful. I just wish we could add political diversity and diversity of thought to that list as well, and not limit or remove any one group from the list.

WC: I loved reading Exit, Carefully. It’s unusual, and in my opinion exciting, to publish a play without previously receiving a major production. Did you write Exit, Carefully intending it to be performed or read? And how’d you go about the process of writing your first play?

EE: Wow, thank you so much. That means so much coming from you, Walker. I wrote the play completely in a vacuum and have no idea if it is any good. I did not write it with any intention or thought it would ever be performed or read by anyone affiliated with theater or playwriting. I wrote it because I had wanted to write it since I was nineteen or twenty, when I first had the idea for it, for this Christmas Eve encounter, the four characters . . . A couple years ago, maybe around 2018 or 2019, I finally set out to do it. I first read twenty or thirty plays by various playwrights: Tennessee, Albee, O’Neill, Shepard, Miller—along with biographies and documentaries on a few of them, as well as some filmed versions of their plays, and a handful of live theater experiences—and then also some more contemporary playwrights: Sam Shepard, Jason Miller, Kenneth Lonergan, much more recent plays. I saw The Waverly Gallery performed in 2019—it had a large influence on Exit, Carefully, the characters’ addressing of the audience in particular.

Reading what makes us uncomfortable—a thriller in which a woman dies, perhaps—can lead to great discussions, less discomfort. If you vet, you never have the important conversation.

Then, finally, I just wrote it. I just did my best to emulate the other plays as I told my story. I worked on it for six months to a year. Maybe longer. And then read it aloud one night with three friends.

WC: Exit, Carefully is dedicated in part to the memories of Tennessee Williams, Edward Albee and Eugene O’Neill, and it structurally and stylistically resembles Long Day’s Journey Into Night and Williams’s memory plays. What drew you to these writers? What do you feel your relationship to them is?

EE: Well, I watched the film version of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? as a teenager and sort of became obsessed with it, with trying to figure it out, solve the mystery of what George and Martha were talking about, the child, the boy . . . I also watched Streetcar as a teenager, and some of the filmed versions of Tennessee plays. And more recently, in 2014 or 2015 I watched every Tennessee play that had been made into a movie. I read a really fascinating biography of Tennessee. I read more plays by Albee. I read and watched Long Day’s Journey. I read a biography of O’Neill. And I came to feel a kinship with Tennessee, especially. I drove to Key West by myself in 2019 and went to the Tennessee Williams museum. I stayed at the Hotel Elysee in New York City where he died. I loved all his older (women in their thirties and forties!) female characters that seemed to be a stand-in for him. I identified with them. Just as Albee’s characters had always reminded me of my own family members—loud, alcoholic, combative, argumentative, tender, vulnerable, human. And to an extent, O’Neill’s characters as well.

The more I read these playwrights, I just came to feel more aligned with them, in some emotional way, than I did with other writers, writers of novels and short stories. I don’t know why, exactly. I love the immediacy of plays, the performance, the aliveness of the characters. I’ve always loved film. But plays are more intimate, I suppose. I feel a closeness to and an empathy for Albee and O’Neill and Tennessee, and for their characters. There seems to be more complexity, more humanity, often, in plays than in novels and short stories. I’m oversimplifying. But something like that.

WC: What’s next—for you or for SF/LD?

EE: Well, personally, I’m working on My One-Hour Comedy Special, which I’ll let the title speak for for now. I’m excited about that. That’s my summer goal. As for SF/LD, I honestly never know if I’m ever going to publish another book until I do. So these could be the last five books, or there could be another twenty down the road. I honestly have no idea. Right now the concentration is on these five that I just released. That’s as far ahead as I can see.

__________________________________

Her Lesser Work and Exit, Carefully by Elizabeth Ellen are available now from Short Flight/Long Drive Books.

Walker Caplan

Walker Caplan is a Staff Writer at Lit Hub and a writer/performer from Seattle.