Elizabeth Acevedo on Fun with Footnotes, Family History, and Alpha Vaginas

In Conversation with Maris Kreizman on The Maris Review Podcast

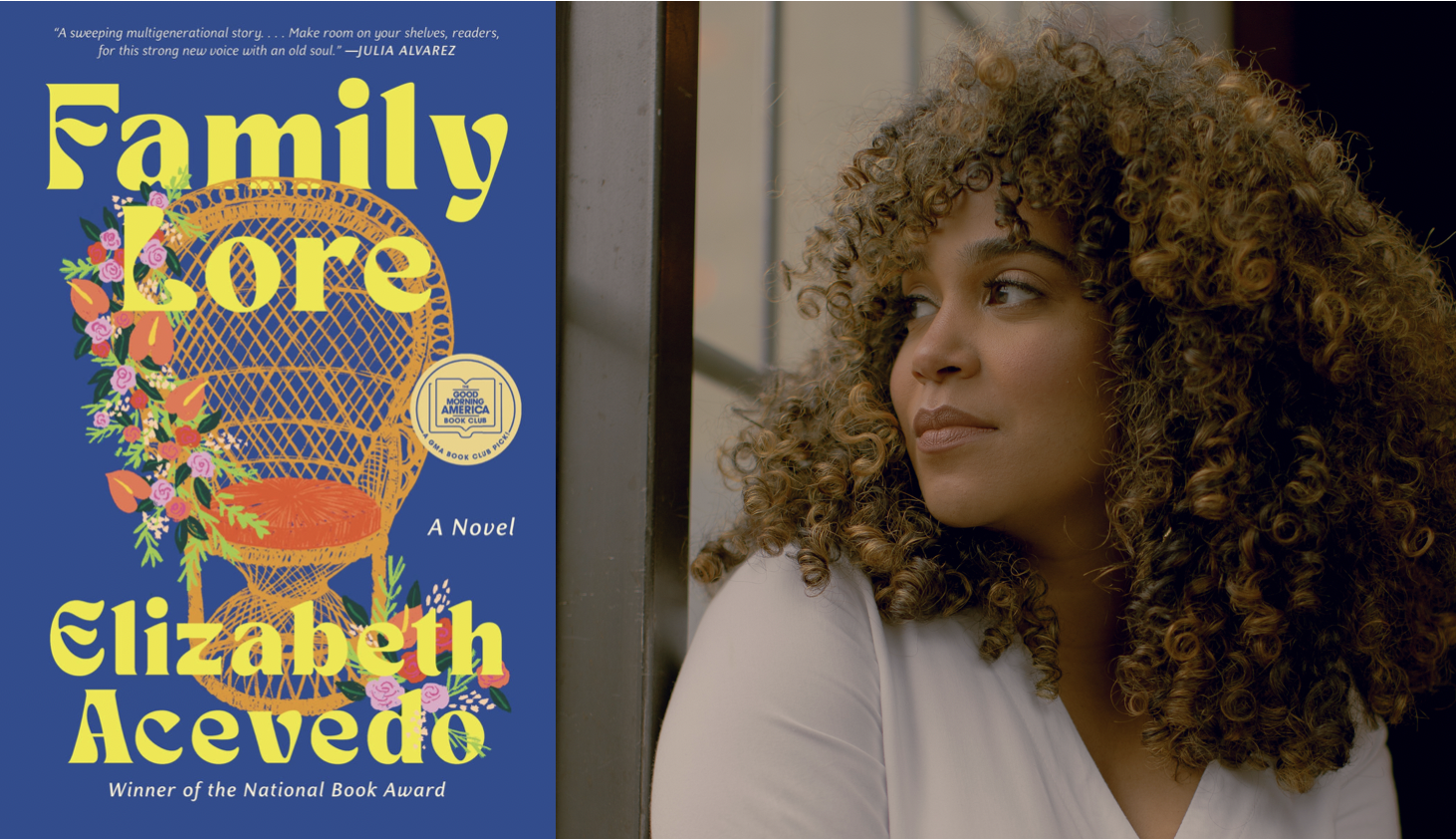

This week on The Maris Review, Elizabeth Acevedo joins Maris Kreizman to discuss Family Lore, out now from Ecco.

Subscribe and download the episode, wherever you get your podcasts.

*

from the episode:

Maris Kreizman: I love that Family Lore is this big intergenerational story, but the narrator is an anthropologist. And so that allows her, and you, to break into various narratives whenever she chooses with some needed facts. Tell me about that.

Elizabeth Acevedo: Yeah, I’ve always been intrigued by novels that are disrupted and I like having windows into the text that exist outside of the world of time, of the text. I’m thinking here, if you’ve read the poets, you’ve seen that there were writing assignments that would come in, there would be text messages. Just these ways in that would kind of leave interiority.

I did it with The Fire on High as well, but I’m thinking here of Oscar Wao, where he would have footnotes. More recently, Chain Gang All-Stars by Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah, where he has footnotes as well. I didn’t wanna do footnotes, I had abstracts that would kind of come in after every other chapter. But it didn’t work. It didn’t feel good. It didn’t fit, it felt too unclear what the narrator’s anthropological research was. And so I kind of began writing these asides. All of the abstracts turned into these little moments of literally disrupting the paragraph to just give the narrator’s take.

And then she would quietly exit and the story would continue. And I love that because this is a book about collecting oral history and oral storytelling, and I don’t know about you, but I can’t listen to a story without, at some point being like, oh my God, that reminds me of… Or, you disrupt, you push, you’re a part of how the story gets told. And once I realized that was the rhythm, that the narrator was integral to the kinds of stories being told and the questions being answered, it started making sense why she had her own two cents kind of always sprinkled throughout.

MK: She’s an expert in so many areas, both in her family and then the field of anthropology. I was googling a lot while I read this book, I don’t speak Spanish well, but it turns out the name of the narrator is short for something. I wanted to ask you about her namesake who fought Christopher Columbus. Both of them clearly hate him very much.

EA: I think I dropped exactly once in a scene with an old lover where you hear her full name and then otherwise you get her shortened name. But, Anacaona was an indigenous cacique, or leader. There were matriarchal leaders throughout the Taino history, and Taino is the name for the indigenous people of the Northern Caribbean, so the Greater Antilles. Anacaona tried to work with the Spanish, tried to work with the commanders that Columbus had left while also on the low leading rebellions.

But she was murdered in a horrific manner. They set her on fire. And her nephew ended up, you know, attempting to redeem her. He was one of the last of her line. But she was really the last caste that took a stand against the Spanish, and was fierce. Was fierce and was loved and was really trying to do what was right by her people when she realized like, Oh shit. These white folks are kind of evil. They’re not leaving. Like, I thought they were gonna visit and keep it going. They’re not leaving.

MK: What a great namesake for a narrator who is very much talking about the kinds of magic that members of her family have. There’s a point when Ona says, It’s not like white people magic in movies. Their magic is not orderly. It doesn’t come out at the most convenient times. How did you set that up? How does the magic work or not work?

EA: I think in traditional world building the system of rules of how the magic is developed… Harry Potter gets his letter when he’s 11. Like there’s this particular rule setting, which allows people to understand it. But that’s the world of fantasy. I think when we’re talking about communities that live in magic every day, and they’re either religious aspects or their cultural aspects is in relationship with magic.

There’s a fluidity there that I think doesn’t really align with the way that magic is often written about. It’s not fantasy. It is the everyday. The supernatural is in and out. Your life is permeated by the supernatural. And so I wanted it to feel that way. Like it’s not something that is easy to describe. Each woman gets her quirk or her talent or her magical whatever at a different age or not at all. It’s in the body, it’s also in the cerebral. Like someone can tell when you’re lying, but that’s in the gut. Someone can dream something, but also you could inherit a taste for limes.

I didn’t want it to be a single system of magic. There’s no like telekinesis, there’s no teleportation, you know, in the way that we think of superpowers. But there is just a little bit of the uncanny in all of them. And it’s not a thing that can be easily held. It’s one of the reasons why Ona had never really looked inward to consider her family as a subject because it was just so normal for her. And none of them use it for their career. None of them were making money off of it, it’s just who they are.

MK: Ona’s little magical quirk is a biggie. I really enjoyed hearing about it, and also hearing all of the synonyms for it…

EA: You know, it’s really hard to find a lot of words for your vagina. I thought that would be a long list. I’m like, we’ve used that twice already.

MK: Tell me about that specific magical aspect.

EA: I didn’t know if this was actually gonna stick. I talk to my best friend every single day. She lives in New York and we’ve been best friends since we were five, andI left for college in DC at 18. And we still talk daily. Very different walks of life, very different kinds of women, but we find each other hilarious.

And one day I’m just talking to her and she is like, yeah, I got everybody in my job to get their period because I have an alpha vagina. And just the way she said, there was no irony. It was just like, yeah, that’s just who I am. And I think that’s a myth. I don’t know that menstruation actually works that way, but I love the idea of claiming a vagina as just this uber powerful thing that can maybe affect the people around you.

I didn’t even know the name for vagina until I was way too old to know its official name. My mom didn’t really talk to me about it, didn’t really talk about my period. There was so much that I discovered on my own that I was moved by a character that fully reclaimed pleasure and her body and her vagina as this site that, I don’t know. It was unfuckwithable. I just kind of moved with that. And then when her story kind of started coming out for me and realizing maybe she had a different relationship with her womb and what does it mean for all of those interconnected organs to be one site of trauma and harm, but also of joy, and pleasure.

Then it became a more nuanced story of what an alpha vagina could be. It was like, let’s talk about this thing that, especially in Dominican culture, we hint at, and it’s in the music and sexuality’s in the music, but we are also very proper about it. I loved that that was her power.

MK: I did too. One of my favorite things about the book is, a lot of it is the aunts recollecting and talking about their past. But one of the things that we get to see is that all of the relationships with each other are different, and one sister’s relationship with their mother can be really fraught and terrible, and one can be nurturing. That’s such a tough pill to swallow that the same people can show different faces to the people you both know and love.

EA: Yeah. I think I was intrigued by trying to figure out how do people in big families who have very different relationships with each other kind of make sense of the experience that they have or don’t have in these interconnected groups. For sure Mama, who is the, the elder’s, lady’s mother and Ona and Ari’s grandmother kind of had a very different relationship with each of her daughters and with her son and then with her granddaughter.

And there was, there was harm. And there was neglect. And there was love. And I think so often when we are harmed by people, we want to know that the people around us also felt that, that we are in unity. And then when they’re like, that’s just not my experience of that person iit can be a hard thing to navigate. Because just because it’s not your experience doesn’t mean it didn’t happen. But also what does it mean that this person could do this to me and not to someone else? And so those questions created a real engine for how the characters dealt with each other.

Even the sisters break down into different groupings and they see each other differently and they hold and are tender towards each other in different ways. It’s this constant tension of, not even favoritism, but of, how do you love me? What is love here? What does it look like? Who do you love more? How do I love you back? For readers who go back to the interviews, you’ll see that the majority of Ona’s questions to her family aren’t on the page but the answers are all about love, right? And so we can posit.

Ona is trying to figure out that same question that I was trying to figure out: how do we learn love? How do we practice love?

*

Recommended Reading:

Red at the Bone by Jacqueline Woodson • The Secret Lives of Church Ladies by Deesha Phillyaw • Above Ground by Clint Smith

__________________________________

Elizabeth Acevedo is the New York Times-bestselling author of The Poet X, which won the National Book Award for Young People’s Literature. She is also the author of With the Fire on High and Clap When You Land. She is a National Poetry Slam Champion, and resides in Washington, DC with her loves. Her debut novel for an adult audience is called Family Lore.

Photo credit: Denzel Golatt

The Maris Review

A casual yet intimate weekly conversation with some of the most masterful writers of today, The Maris Review delves deep into a guest’s most recent work and highlights the works of other authors they love.