Elif Batuman: On the Russians, the Telephone, and Hyphenated Identity

Paul Holdengraber in Conversation with Elif Batuman

This week, Paul Holdengraber calls Elif Batuman, who has been a staff writer at The New Yorker since 2010. Batuman’s first book, The Possessed: Adventures with Russian Books and the People Who Read Them, was a finalist for the NBCC Award. Her stories have been anthologized in Best American Travel Writing and Best American Essays anthologies. She is the recipient of a Whiting Writers’ Award, a Rona Jaffe Foundation Writers’ Award, and a Paris Review Terry Southern Prize for Humor.

In part one of their conversation, Paul Holdengraber and Elif Batuman discuss, among other things, a writer’s aversion to the phone, the alienation of the hyphenated American, and the Russians, always the Russians…

Elif Batuman on the common aversion to the phone…

I only talk to writers mostly, so if writers don’t like the phone, then I figure it’s because writers like to write. It’s like haters are gonna hate, and writers are gonna write.

Elif Batuman on moving to New York City…

I’m living in New York City for the first time. And there is a certain sense that—I don’t know if it matches some kind of memories I had from when I was a kid, or if it’s that New York is what you see in movies? I don’t know where it comes from. But [New York] corresponds with some idea I have of real life that other places I lived somehow did not correspond to. So it feels somehow like going out and buying a phone, okay, now I’m doing the adult thing that should happen eventually. In that sense it feels like home. But in lots of other senses it feels very bizarre.

Elif Batuman on living in Turkey, her parents’ homeland…

I was there between 2010 and 2013. In 2013, the Gezi Protests started, and journalists were starting to get arrested and the government was becoming more authoritarian. And I would be on the phone with my parents who were constantly—they didn’t put it this way—but [they] were both urging me to come home. And I could tell that they were like, We didn’t uproot our lives and come to America thirty years ago so you could get hit on the head with a tear gas canister in Istanbul. So it was like I went and mirrored the same thing that they did, and made the same distance between [me and] them as they has made with their parents.

Elif Batuman on the alienation of the hyphenated identity…

When I was growing up, I felt foreign because I was going to school in New Jersey where I looked a little bit different than the other kids, and my name was definitely different and had to be explained to everyone. I was different in various ways and I felt a little bit foreign. And I had it in my head that, Oh, the reason that I’m foreign is because I’m partly Turkish…People say, “What are you?” And you say, I’m Turkish, I’m Turkish-American. So then I thought that when I would go to Turkey, I’d feel more at home, but instead of course I felt less at home, because it’s a place I almost never was. And just the fact that I had a name that sounded very indigenous to people didn’t do anything to mitigate the feeling of alienation. If anything it exasperated the feeling of alienation because I speak Turkish with a slight accent. I go to Starbucks sometimes and they ask for my name. They’re expecting a foreign name, and when I say Elif, they’re surprised. So having a Turkish name is a liability for me in both American and in Turkey.

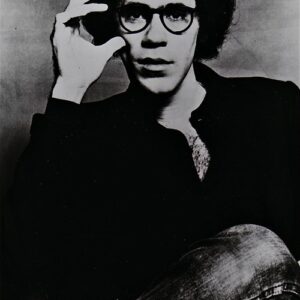

Feature photo by Korhan Karaoysal.