Elegies of Sorrow and the Crow: How to Process Grief and Loss Through Storytelling

Caroline Hardaker on Max Porter, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Yoko Agawa, and More

Grief is the most universal of all human experiences. Grief turns us inwards. Grief permeates flesh. Grief twists our gizzards. Grief squats inside our innermost parts; a toad in a festering pond. Grief consumes. Grief eats its way through whatever other emotions strain to rise beside it. Grief casts a deep, impenetrable shadow over our eyes, tainting everything. Staining. Turning iron into rust. This is an incredibly lonely place to be, and so it’s common for the grief-stricken to turn to literature to find solace, understanding, acceptance, and hope. To discover shapes into which they can pour their own grief to make it make sense.

Literature is the resting place for loss. It’s where writers go to express the inexpressible—just how can life possibly go on when all the lights go out and we can’t see the path ahead? In my own writing, grief has been the basis for exploring a wide spectrum of human loss—from the searching for companionship after the death of an inspirational mother, to grief contributing to a complete break with reality.

From traditional elegies to dark, speculative fiction—grief, loss, and bereavement have been torn open, dissected, and stitched back together by creatives in a wide range of exploratory styles, each one unique in its handling of the nuances of personal struggle and eventual finding of the light.

The elegy is a particular poetic form in which the poet, author, or performer expresses personal grief, sadness, or loss.

Originally, the elegiac form began in ancient Greece and would have been written as a direct response to a death. Though similar in function, the elegy is different from the traditional epitaph, ode, or eulogy. The epitaph being very brief; the ode celebrating and raising the subject high; and the eulogy most often being written in formal prose.

The elements of a traditional elegy reflect three stages of bereavement, beginning with a lament expressing grief, followed by praise and romanticisation of the dead, and finally consolation and solace. One famous example being; “O Captain! My Captain!” by Walt Whitman, written in honor of Abraham Lincoln.

Elegies are all about the proclamation of loss—a public sharing of grief that seeks to reach out and connect a community of listeners. They portray a journey of grief, ending with the distant glimmer of hope or peace.

While elegies are constrained by their storytelling form, poetry is loose, freeing, and harder to confine. This is a prime reason for poetry being a common literary form for expression of grief.

Processing grief requires action. Writing poetry is an action that can provide a structure to help identify, express, and capture grief, bereavement, and loss at every stage of the grief journey.

Poetry’s refusal to confine the writer to usual speech rhythms or syntax allows it to express the inexpressible, and its ability to splice together unusual combinations of images can create jarring and sometimes shocking pictorial depictions of loss.

The contemporary poet, Wendy Pratt, offers many fine examples of unusual pictorial portrayals of grief that poetry can conjure. In her first short collection, Nan Harwicke Turns into a Hare, Pratt connects witchcraft with the emotional processing of a mother mourning an unborn child. In the poem of the title name, the narrator literally becomes the hare, rooting herself in its belly and stretching out her limbs to inhabit its wild body: “I slipped / into the hare like a nude foot / into a glorious slipper.” As Nan stretches out into the hare, she uncurls from its core, reaching out into the legs, the frame, and the skull, so that the skin is worn like a glove. Nan’s inhabitation of the hare mirrors the carrying of an unborn child, and how that child (though curled in the womb) reaches out and lingers in every part of the mother’s flesh after death.

Processing grief requires action.

In Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s nineteenth century poem “Grief,” the poet compares the feeling of raw grief to a tangible, weighted object, a statue: “Deep-hearted man, express/ Grief for thy dead in silence like to death— / Most like a monumental statue set / In everlasting watch and moveless woe / Till itself crumble to the dust beneath. / Touch it; the marble eyelids are not wet: / If it could weep, it could arise and go.” Here, Browning uses short, punchy sentences to depict simple, relatable yet haunting images which build and layer upon each other, until together they form the depiction of a living-dead figure — very much still, but aching with grief. Indeed, this is a relatable portrayal of an individual lost in the deepest part of bereavement.

Of course, contemporary literature needn’t be confined to a single form or genre. A rise in the popularity of poetic prose blends the lyrical mastery of metaphor and rhythm with coherent storytelling and stream of consciousness.

In a sense, poetic prose blends an inner world of grief with the poker-faced composure of the bereaved in public viewing.

Max Porter’s Grief is the Thing with Feathers explores loss through a reinterpreting of Ted Hughes’ “Crow.” Porter’s short, experimental novel—part fiction, part fable, part song—follows a family as they come to grips with their wife and mother’s sudden death. The story jumps between the perspective of the father, his sons, and the enigmatic and mischievous Crow. The reader is treated to snippets of the family’s daily life and memories, thrown together like laundry tumbling in a washing machine. But it’s Crow who leads the family in their days and nights of grief. His air of madness and irreverence is the filter through which the reader witnesses the family’s mourning, the effect feeling like a kaleidoscope turning, never settling, and twisting reality.

Porter’s mix of poetic, idiosyncratic prose allows for deep ruminations on loss that mirror an uninhibited stream of consciousness: “Ghosts do not haunt, they regress. Just as when you need to go to sleep you think of trees or lawns, you are taking instant symbolic refuge in a ready-made iconography of early safety and satisfaction. That exact place is where ghosts go.” Simultaneously, the poetic repetition and musicality captures snapshots of the grieving father’s daily life which come across as overstimulating yet vital and bursting with life: “And the boys were behind me, a tide-wall of laughter and yelling, hugging my legs, tripping and grabbing, leaping, spinning, stumbling, roaring, shrieking and the boys shouted I LOVE YOU I LOVE YOU I LOVE YOU and their voice was the life and song of their mother. Unfinished. Beautiful. Everything.”

The increasing popularity of blended genres in fiction has also seen the rise of speculative fiction, an area of science fantasy addressing “what if?” scenarios, frequently in the style of a dark psychological drama with a near-future setting.

In Yoko Agawa’s The Memory Police, the grief explored isn’t the loss of a physical person or object, but the loss of knowledge and personal history. Truly, the most terrifying part of The Memory Police isn’t the overarching totalitarian regime or even the everyday objects being stolen from everyday lives: it’s living with the fact that there are growing voids in your memory that can’t be controlled or ever filled again. It’s a loss of control and a loss of self, leading to a loss of connection with others and their place in the world.

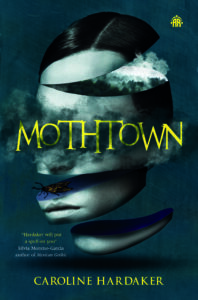

In my own speculative fiction, I turn my lens on the consequences of personal grief. In my first novel, Composite Creatures, the protagonist, Norah — still mourning the death of her mother—signs up to an exclusive, experimental “life enhancement” programme which promises life, partnership, and enhanced longevity. Despite the horrifying consequences, Norah plunges deeper into the life offered in her desperate need for validation and love. And in my second novel, Mothtown, the protagonist goes on both a physical and metaphysical journey following the death of his closest relative when he is still just a boy. This grief-stricken road takes David through a Kafka-esque transformation from boy, to man, to other, all while searching for the open arms of comfort. Of home. Here, I utilize surrealism and psychological horror to reflect the confusion and disorientation of a world shaped by a loss.

There is almost infinite scope for experimental portrayals of bereavement. Grief and loss are embedded in human experience. As we embrace new things and people, we must also accept that we will likely lose them one day. Literature explores just how this loss bubbles and bursts within us, its different forms allowing writers the scope to dissect the idiosyncratic effects of grief, while readers can pour themselves into the characters and lyrics, finding shapes for their own experience of grief and sorrow.

__________________________________

Mothtown, by Caroline Hardaker, is available from Angry Robot.

Caroline Hardaker

Caroline Hardaker is a poet and novelist from the northeast of England. She has published two collections of poetry and a novel Composite Creatures. She is Writer in Residence for Newcastle Puppetry Festival and is currently collaborating with the Royal Northern College of Music to produce a cycle of songs to be performed throughout the year. She lives and writes in Newcastle.