Eileen Myles Remembers Bobby Byrd

“His world was huge and specific.”

I guess Bobby was Texas to me. That’s why when I look at his poems or re-read the pieces that came out when he died a month ago I begin sobbing. Texas or Bobby was home. He was my friend and not all friendships are the same but the one I had with him felt like home. That might be the Bobby feel. His death seems both impossible and real at the same time because for over almost forty years he was consistently (though erratically) embedded in what I know of as my life. Bobby was even, he seemed that way, he had a folksy stateliness and I am often in a rush. He had big blue eyes and he managed to seem happy and sad at the same time. His poems were so good but it felt like he sang his actual existence. He was an all-the-time poet. It was a very nice pace. So it’s a selfish wish that makes me want to write about him now. I miss him, I miss Bobby-time and I always will and I can’t get it through my head that he’s not here. It’s too soon. And maybe it will always be that. Bobby Byrd was a poet and an inspired publisher and a wide and generous family of a man. He made it all cool. He was a citizen. He even gave birth (with Lee) to a daughter, Susie, who became a politician. (There’s also a son Andy Byrd who doesn’t work for the press.) But Bobby lived in El Paso and had for all the time I knew him. Though originally he was from Memphis. I’ve had three friends in my life from Memphis, now all dead and all three had a way of saying Ah-leen that I now fear I won’t ever hear again. I’m sitting in Provincetown Mass and I am here very much for the accent. Part of the friendship I felt with this poet, Bobby Byrd (1942-2022) is simply a musical thing. I miss the sound of him.

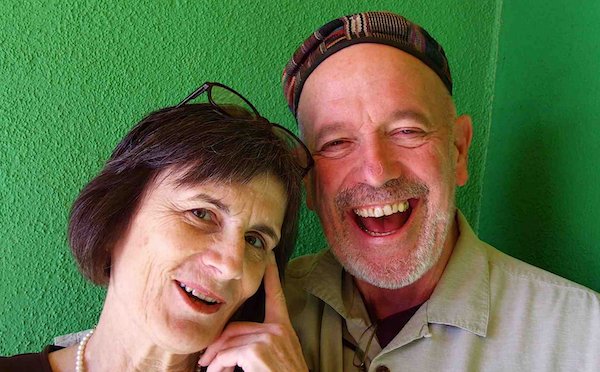

Lee Byrd and Bobby Byrd. Photo by Debbie Nathan

Lee Byrd and Bobby Byrd. Photo by Debbie Nathan

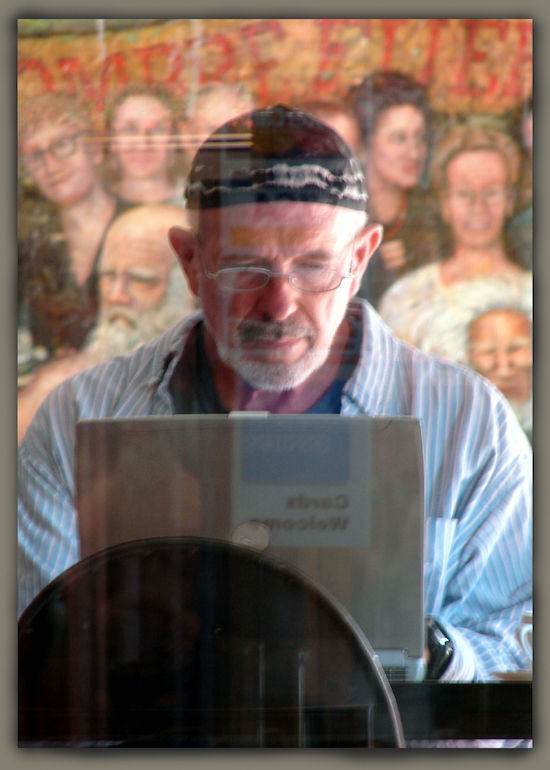

Photo of Bobby Byrd by Cesar Ivan

Photo of Bobby Byrd by Cesar Ivan

I was working at the St. Mark’s Poetry Project in the mid-eighties and part of the gig was getting slammed by requests from other poets to read at the church. It was confounding to me, a very young thirty-something, that all these poets were acting like they were the poet and I thought me sitting there director of this great poetry institution meant that I was the poet and for about two and a half years that job totally messed with my way of thinking. I don’t recall the letter Bobby wrote (though I bet it’s in the archives!) but he definitely mentioned his connection to Paul Blackburn who he met in Aspen as why he wanted to read here. He included his poems and I liked them. But it was all connected. He was born in 1942. Part of my mission then at St. Marks where I had grown up as a poet was this commitment to diversity which in my paws (since I believed my cohort Patricia Jones had people of color “covered”) meant queers, young people, working class people, “regular” folk. Because I was one of them I liked people who didn’t sound like poets. I’m not sure that working class is even the right way to describe Bobby, I will ask his wife Lee Byrd, also my friend. I think I mean someone somehow from the real world, a person. I arrived in New York knowing no one. Bobby knew more than me already, he knew Paul which was how he referred to him. He felt like an outlier somehow, this guy from Texas who was nonetheless one of us. The Poetry Project if not started by was inspired by Paul Blackburn. He was the translator poet dude who carried his giant reel to reel from reading to reading, and those tapes were the beginning of the institution that created me poetically. The living poets like Ginsberg and Ashbery and Anne Waldman all trumpeted that it was a real and present world (enhanced by the glamourous invitees I heard read: Denise Levertov, Gwendolyn Brooks, Bukowski, Audre Lorde) but there is just this way that poetry inevitably feeds on the past, it must, language is old, and Bobby put his Blackburn front and center (and Blackburn was connected to the troubadors, like Bobby). I wrote back and said please come. And what I remember from this person who came to New York in possibly 1986, this is an inexact telling, is a guy about 44 in a pink shirt, tucked in in jeans, a good-looking guy with what I still call a Caesar cut, short bangs hitting the middle of his forehead who gave this great reading, had a warm convincing voice and was clearly shockingly a nice man. What does that even mean. I liked him. We became friends. Not immediately but over the years in that slow way in which you realize at some point in time that you have known this person forever and they are in your family. Being friends with Bobby meant I was now in his world. And his world was huge and specific. The press he ran with it seemed his entire family, especially his wife Lee Byrd, who was also a writer and their son Johnny was named Cinco Puntas after the neighborhood they lived in in El Paso and through them I met the poet Rosa Alcala, I met Benjamin Saenz, and the journalist Debbie Nathan and at that point I stop knowing who I met through Bobby, or Debbie, or who initiated the El Paso wing of my 1992 Presidential campaign. It was all Bobby’s immediate world—Texas, the border and Mexico. Nobody else (Well maybe Deep Vellum) was doing this kind of reaching across into Mexico and into South America (not invading but embracing) that Cinco Puntas did that acknowledged through books that the land was all one. They got in trouble when they published the children’s book by Subcomandante Marcos at the beginning of the Chiapas conflict and the NEA pulled the money and Lannan filled the gap but Cinco Puntas and Bobby and their collective world view was astonishingly right and they had the gusto and the nerve and most important they published what they liked and got fearlessly in debt, a hard weight to carry for a mom and pop press truly, but they did what they believed in and that was their life. [1] Bobby was a buddhist. How tall was he. I’ll have to ask Lee. He was a big guy and he had a little hut in his backyard where he sat and I think he had a group of friends he meditated with in some fashion during the pandemic. He wasn’t a holy man, he was regular holy and what there is and what that was inflected his work and his life. As I breech it again makes me cry. I think what we did besides eating and talking and doing readings together is walk around. In El Paso, in Juarez. We went to galleries. We did it in New York too when he came to book fairs. I looked through our email correspondence and one of us, either me or Bobby is usually asking for something. I liked to think we filled a need. I blurbed books and sometimes helped people do readings in New York, and I always read in El Paso through and often with Bobby, Rosa Alcala or both. Bobby and Lee let me stay in their house again and again. I moved to Marfa in 2015 and it got even more frequent. There was a little room in back I think of as mine right off the second bathroom which a granddaughter has now taken over so that was done. I took so many early flights out of El Paso having that oatmeal with raisins and nuts that stood in a pot on a stove in he and Lee’s kitchen. Now I feel they were the only family I have. Just thinking about getting off a plane in El Paso and going to them. Can I park here. Can I leave my truck. I hear they are stealing catalytic converters at the airport at El Paso. Can I leave the Prius there. I even drove cross country once and spent the night with them and I was travelling with a black cat named Ernie and their neighborhood, the famed Cinco Puntas entirely resembled the canyon neighborhood in San Diego where I had a teaching job a life I was now leaving. Ernie was headed to a New York apartment where he would have to stay in. I remember Lee asking if I was sure Ernie wouldn’t be happier staying here, she meant in her house. No I retorted. He’s coming to New York with me. At the beginning of Ernie’s second summer he was standing at the window and crying for the world because cats in New York who go out never come back and he had also taken to jealously biting my new girlfriend’s head while she slept I knew it was time. I called Bobby. Remember when you guys talked about taking Ernie. Were you kidding? Ernie wound up living between about three homes in El Paso just as he had done in the canyons of San Diego. He was the king and now our friendship became so many Ernie stories and pin ups of a hot black doggy cat—on my website you’ll see Ernie in a final shot with a weird piece of fluff on his face that Bobby took. Bobby killed him in fact and I mean this in the kindest way. Ernie had taken to lying in the street or the driveway and daring the world to run over him. By the end of his life (and he was old, about 14) he wasn’t so fast so when Bobby pulled into his driveway one evening and three cats were holding court there only one failed to get off his ass and Ernie was run over. They took him to the vet and frank poet always Bobby said when he held Ernie under his butt and legs he felt like a bag of marbles. We let him go. I wish we were as kind with humans but Bobby’s end was fast. I came through in April not staying with the Byrds but I had dinner with Bobby and Lee at a great restaurant, the JVB, and of course they knew the family that ran it and what college their kid was going to and had known them for years. At some point Bobby started coughing and went outside and I don’t know if he entirely explained that he had barfed but it seemed like something was wrong and it was a great dinner. I left my car to forestall the dreaded robbery and when I came through next I was only there for less than an hour. I wanted to get every bit of light I could on my return trip to Marfa so I mustn’t tarry and Bobby reminded me as were leaning on the car or maybe it was Lee that his 80th birthday was in two days. You’re probably not going to want to come back Bobby suggested gingerly. I like not deciding so I blurred my response in some way. Oh let me see how it feels. I want to I vowed! And I did. I was writing some ill-fated piece for the New Yorker about Cape Cod. I needed to pounce on my computer and drum it out. For those two days I was thinking about Bobby. I wrote Tim Johnson, poet, book dealer in Marfa, also Bobby’s friend. Are you going to Bobby’s 80th I texted. By then I was no longer sure—It’s Saturday right I wrote Lee. I had of course reinvented the schedule which I do. It was Friday she wrote back and it was great. I talked to Bobby later on and everybody in the world was there and there was shrimp and poetry and music. You would have had a good time. People would have been very happy to see you Bobby said generously. I think he and Lee even came through Marfa and were having dinner with Liz Rogers at Cochineal and I was lying in some exhausted state from something or other and I decided I couldn’t make it and nobody seemed to mind. Stay home said Lee. And then Bobby was gone. A group of poets had serenaded him outside his window as he was laying inside in bed. The salient fact about Bobby is that he affected people, he welcomed everyone and he was truly loved. It’s funny I was walking down Commercial Street last night which is virtually an arcade, selling fudge and wiseass tea shirts and every hippy dippy new age item you might want and then of course clothes for styling fags, and cape cod sweatshirts. Ice cream, so much ice cream. And a dog store. One place had a bin of hats outside and I saw that kind of buddhist, jazz musician embroidered hat that Bobby wore. He was pretty bald, and I had not seen the top of his head for a long time. I should buy that I thought to know more what it felt to be him. But the hat was everything and nothing. I write this cause Bobby mattered. Colum Toibin once stayed in a house near the university in Austin and he told me he found Bobby’s great On the Transmigration of Souls in El Paso on a shelf. He loved the book and mentioned this to the owner who said that the book had been recommended to her by Laura Bush. When Colm met Bobby Byrd and told him this, he did not express surprise but said: ‘Yes, Laura likes my work.’ Of course she did. I sob again. I won’t be me in the same way anymore I think and that’s just the way it is when you lose a friend. Bobby Byrd mattered. I want to weep again when I say that because it’s the best a person can do. Maybe I think he was a wise man. In response to some request of mine—I was trying to give money to Beto and Bobby knew him of course. Then I told him my mother was dying. He wrote me this:

Gosh, your letters from always curious and unexpected.

I’m having trouble finding his website but will.

He’s twittered up @BetoO’Rourke.

Will get Susie to figure it out.

Meanwhile, hold on to your mom’s hand.

Hold on for dear life, we all used to say,

The roller coaster making the slow rickety climb up the hill.

B

[1] And they sold the press last year to Lee & Low Books.

*

Cedar Smoke

–El Paso October morning

“Look at the perfect sky,

it says nothing.”

–Gerard Kerouac from

Visions of Gerard, by Jack Kerouac

An airplane way up there

in the wide blue sky

soaring into the someplace else.

Always the someplace else.

Should I be someplace else?

I was two years old when my father died—

1942, Clarksdale, Mississippi,

his plane crashing into cotton fields.

The sky was perfect.

The sky is always perfect.

Mother said I wandered through the house,

saying Daddy, Daddy, where is my daddy?

I light a stick of incense and ring the bell.

The bowl is thick with ashes,

smoke fluttering away with my breath.

–Bobby Byrd

Eileen Myles

Eileen Myles (they/them) came to New York from Boston in 1974 to be a poet. Their books include For Now, I Must Be Living Twice/new and selected poems, and Chelsea Girls. Pathetic Literature, which they edited, will be out from Grove in Fall 2022. Myles has received a Guggenheim Fellowship and in 2021 was elected a member of the American Academy of Arts & Letters. They live in New York and Marfa, TX.