Eileen Myles on Writing With Political Meaning

"Reading is a collaborative act."

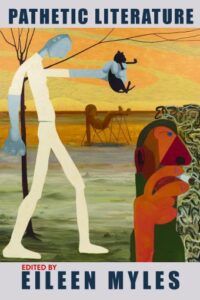

The following is an excerpt from Pathetic Literature, edited by Eileen Myles, and first appeared in Lit Hub’s The Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

In general poems are pathetic and diaries are pathetic. Really Literature is pathetic. Ask anyone who doesn’t care about literature. They would agree. If they bothered at all.

Perhaps the only accomplishment here is I’m saying that as an insider. This book is a kind of hollow. All these pieces of the rock (meaning Literature) long and short are just what I like. The invention of pathetic literature surely is Sei Shōnagon’s Pillow Book. More than a thousand years ago she kept her diaries, her interminable and adorable lists, her sovereignty to herself. Being discovered, she admits, kind of ruined things.

In light of our different pace I’d say we’re ready for ruin.

I need to start this book at the beginning which is to say how I landed on pathetic as a badge of distinction. In the late twentieth century there was a movement in visual arts known briefly as Pathetic Masculinity that has since vanished as a genre and simply became part of what we know. What exemplified pathetic art then was an orientation to crafts, to feeling, to the handmade and diaristic. It was kind of dykey. Using cuddly and abject stuff like stuffed animals rather than producing work that was determinedly abstract. There was a readymade aspect to a lot of it. And it wasn’t just any stuffed rabbit, it was the one you carried with you for all twenty-eight years of your childhood and now even to look at it produces trauma so the objects had secondary meaning too. Which is how it got to be art. And I have to say that pathetic art really pissed me off. Right out of the gate it resembled feminism. I mean give credit where credit is due! Feminist artists had long been appropriating crafts—not to be “natural” as the late Mike Kelley once said in an interview (as opposed to his own “‘ironic’” use of similar materials) but to deliberately hijack the production of doilies and hand-sewn cushions and knowhow away from the den of the patriarchal family in order to pump up the pleasure in collective women’s spaces and community activism.

Other feminists, Eleanor Antin and Mary Kelly, seized on the ubiquitous graphs and diagrams of sixties and seventies conceptual art to chart the veracities of domesticity like being descended upon by in-laws when you had a new kid. I heard one tale of a giant abstract painting on women’s land that basically was a giant menstrual chart of everyone living there. Feminists were pretty funny and also were using the materials of art to make a statement, to undo something, there was a utopian purpose as opposed to Mike’s being sad or Paul McCarthy bad. Their art was boyishly satanic cause they had suffered too. Nobody in the art world of the 90s “enjoyed” patriarchy (punk was against it) but good men and bad men and especially sad men made a terrific living in there whereas women more likely reaped the pathetic jouissance of community and later academic jobs. The story about seventies feminism is that it was dominated by white women which is not really true but what feminist artists and activists did share was a desire to undo white male dominance and the system itself. The work had a message or was definitely floating in one.

Which gets me to literature in that there are parts of the literary world where one can readily make political meaning with the messily colloquial, the hand-writ, the felt. I mean who gave Judy Grahn the authority to enclose an entire world, all its institutions, in a single poem, “A Woman Is Talking to Death.” Having been tossed from the military for being a lesbian in the early sixties she then turns out to be uniquely prepared to know everything. In 18 pages, so I’ve included the whole thing here. I’m eager for everyone to know this poem, a moment in time and a political folk art masterpiece. The tone shifts at will from vulnerability to pompousness. Lawrence Braithwaite in a chapter from Wiggerslides a peephole open onto a druggy vortex where by means of a bit of graffiti scrawled on an office door an abused kid sends a valentine and rats on his teacher at once. It’s pithy horror syncopated by a poet (in prose). The variegated pieces of the rock in this collection make a whirling system of difference, young, established, yes Beckett’s in here, that old weirdo. But Gertrude Stein isn’t. I actually don’t think of her as pathetic. Burroughs is not pathetic. Ginsberg is. I had to stop myself while this volume is only immense.

I am definitely interested in the surprising edges or the forced march of a riveting pattern. And there’s something indeterminately true about each and every one. Sometimes it’s in the writer’s very willingness to make that gesture at all. To make this of that.

Like Robert Musil said of Robert Walser, he was “sui generis, inimitable,” his work being “not a suitable foundation for a literary genre.” Is that praise? Like you couldn’t start anything here. But what if that lack was the organizing force?

Samuel Delany tells us that in the gay porno theaters of Times Square (circa 1970–1989) men were not only getting blow jobs but were very often making friends. He essays for the dirty fealty of contact over networks. He met his own life partner in such a way. Each of these writers has a discomfort or a restlessness that exceeds their category somehow. Work that acknowledges a boundary then passes it. “It” being the hovering monolith, that bigger thing that confirms. There’s no institution, or subculture, where any of this all belongs. This gathering is not so much queer as adamantly, eloquently strange, and touching, as if language itself had to pause. Less an avant-garde than something really beside the point. Until it begins to steamroll. In literature there are so many little empires. If you begin in the state of poetry and I guess a great percentage of the writing here is that or is poetry-influenced so what we’re really talking about is a teeming hive of mini-fiefdoms. They don’t make an arc—unless it’s toward devastation like Victor Hugo.

I’ve collected whoever’s in here for their dedication to a moment that bends, not in a “gay” way but you know how when you’re walking towards the horizon it seemingly dips. [1] And you feel something. That’s pathetic. It’s an empathetic thing. The light shifts and biologically we turn too. People get different. Take the word crepuscular. The blue moment. Some creatures only come out right then. A lot of the world is trained to think of that part of existence as vacation or what happens during drinks but I’m saying that no I think it feels like a life. As a citizen of the United States I’m always surprised by where I live and how I live. Looking back on 2003 when George Bush was bombing the hell out of Iraq (and Joe Proulx shows us in “An Obituary” what that looked like “on the ground”) it’s clear the destruction of the world trade center handed George an opportunity.

Same way Hurricane Sandy is creating one right now here in New York (after doing nothing for nine years), turning East River Park, the most human playground where little league kids play and families barbecue on the poor side of the river into a vivid real estate opportunity. Rather than “freedom and democracy” they are calling it “flood control.” Because natural disasters yield development.

When I talk about the bigger world, bigger literature, bigger things that’s what I mean. Something with enormous resources and a singleness of purpose. Something that puts women’s names on storms. Is it just white supremacy and patriarchy and capitalism rolled into one. Does it have another name? Gwendolyn Brooks reporting the mundanity of being the only Black people in a movie theater and her 1950s narrator Maude Martha, lovingly noting the apricot stain on her partner’s shirt bring on the embodiment of being Black in this country more than a Hollywood account of Fred Hampton being shot in his bed.

Trayvon Martin got shot in a gated community because there were no Black people “in there” though there were. Racism is a language in the minds of white people that gets read onto the bodies of Black people (undoubtedly occupying their minds too) so that just being with his skittles in the wrong place is reason enough for a kid to be killed. The skittles are pathetic. Everyone knows about them. When Frank Wilderson describes (in Afropessimism) going as a teenager to Fred Hampton’s bullet-ridden apartment (which the Chicago Police Department kept open like a cautionary amusement park for ninety days) on a date, his story authenticates the horror. It inhabits it.

Cindy Sheehan’s 25-year-old son, U.S. Army Specialist Casey Sheehan was killed in action in Iraq and so she met several months later with other military families and Bush who then pretty much kept bombing and destroying Iraq in the name of freedom. So Cindy Sheehan wanted to talk to him again. She sat at the end of George Bush’s street in Crawford, Texas, and waited. They called it Camp Casey. 1,500 people joined her. Sheehan said “if he even starts to say freedom and democracy, I’m gonna say, bullshit. You tell me the truth. You tell me that my son died for oil. You tell me that my son died to make your friends rich. You tell me that, you don’t tell me my son died for freedom and democracy.” She also vowed not to pay her federal income tax for 2004. I mention Cindy Sheehan because I recall a conservative commentator called her that pathetic woman. Her sitting there, her famous act, meant that as a woman Cindy Sheehan was taking more space than she deserved. And that aspect of pathetic is what I am truly interested in here. The act of taking a little less or a little more. It’s the essence of a political meaning. A pathetic man is chatty, effusive, sort of gay-ish in the high school sense of the word but what does gay mean other than nonconforming. The space he is taking is a woman’s. You can’t take the wrong space, a woman’s space and be masculine.

Because gender is a counterweight to keep everything and every body in line. It’s a military formation. It’s our national poetics. We are free to be feminist here (and I remember going to Germany in the 90s on a literary tour and we were floored by how retro and patriarchal the German literary community was. Look at us, we crowed) but contempt flung at any woman who dares to approach the seat of power reveals how flammable, how violently reactive the slimy surface of our freedom and democracy is to anyone even nominally opposed to patriarchy. You can’t even say patriarchy exists. You can barely say in textbooks now that slavery existed. Or jails. Why are people opposed to wearing masks during a pandemic. Has the right to bear arms ever included Black men. We have a language of suppression and it keeps everyone in line and you can’t be too fat or too sick or too ambivalent or joyous or resistant or poor or hungry or loud or unstable (because outside of porn any deviation makes us feel the weight of your body = too heavy for democracy) so show us your type, then we will commodify you into another form of silence. Does Oprah talk or not.

It took about a hundred years for pathetic to mean mean. It went from “pathetical” to “pathetic” in the 19th century and it still meant something touching or pithy, “felt,” but then pathetic went negative real fast. Whatever brings up feeling in here must get squashed. The word didn’t do it by itself, but something closes in on us like a vice and all unlikely approaches will get slapped down. So what you’re stepping into here is a tiny monument for witnessing change, not of any one sort but of many sorts like a sex club of thought. A bar that serves only time in different and peculiar-sized doses.

When I saw how good Porochista Khakpour was at talking about being sick, what lengths she went to, how many plateaus of suffering she endured, I was delightedly aghast. She could just go and go. It’s so bold. It reminded me of what I once heard a male critic say at a party about a female artist. She’s an endless woman. The room got quiet. He had named his fear.

I’m not sure I can ever truly stay inside of the mind of Robert Walser. It makes me so uncomfortable. I first learned about him one day in the 80s on a drunken visit to poet and book dealer Gerrit Lansing in Gloucester, Mass., who regaled myself and David Rattray with a description of this Swiss writer from the turn of the century who wrote in bits and pieces changing directions at will depositing an entire novel on the corner of a napkin, doing everything at the absolutely wrong scale. Almost topographically, if you know what I mean. And in his almost manic directionlessness he created this extra space. He was sent to review a play and he reviewed the audience. It’s like ADHD taken to a pitch where it becomes useful if not spiritual. It was infectious. I didn’t read Walser for another ten years but even hearing about him gave me permission to write prose for the first time—if I could be volumetric. Take that pill and grow larger and then scrunch myself up if I wanted to be small.

The act of writing as we know is pathetic. I want to go out but I want to stay in. What torture it is to do this. I’m thinking about the enormity that Lucille Clifton conveys in simply looking at the bench that held the ass of a woman who was enslaved her whole life (Aunt Nanny) who could spell her own name and did it right here.

There’s no monument anywhere in America just like that because it’s pure apprehension. Ivan Dixon’s 1973 The Spook Who Sat by the Door actually showed Black militants holding guns and shooting white soldiers so of course our government would not let that be screened anywhere in the world for at least twenty years. And shouldn’t art make an action outside itself. That’s what I mean by feeling. Qiu Miaojin’s writing tugs inexorably toward her death, first Bunny (the pet rabbit) dies in the book’s dedication and now Zoë (Qiu) will die. And Angie is dying and Ed is dying and Nate’s mother died. And each death happens in a solution, in a differently constituted percentage of love or lovelessness. AIDS is a lot of the reason for this pathetic book. Some of us knew all about dying in the 80s while others were still whispering about who their one gay friend may’ve gotten it from. Just like now with covid where the people who die are often not my friends and entire zip codes in New York City have been decimated. The selectivity of the virus explains the resistance to the mask. What’s been politicized is a feeling that the disease knows who we are. It’s almost sung. I remember everyone’s horror when Dennis Cooper said AIDS ruined death. What we did learn is that everyone dies different. The horror of life is that everyone is dying, not now but eventually. It’s a horrible pact we make with existence and we became connoisseurs of how differently people get at it.

Looking at death, imagining it. Literature, this scraping sound, is a way we deal with that one unknowable space. I’m afraid of death, of my friends who are dying. I was afraid to go see Allen Ginsberg when he was dying. I was welcome (I think he even called me) but I was afraid to be that close to him at the moment (like Allen had to do all the loving) so Rosebud’s document gathering every pointillist detail of Allen’s dying still feeds my sense of loss at not having the courage to walk in. Each shred of story in here is a little machine of feeling that bends like this and that. Charline, my European friend, smiles at the difference between our pathetic and the one embedded in any romance language. It got ugly here. It should be our motto. You could say we invented slavery because we made it be our economy. We became modern. We made it everything and now we don’t know where to hide it. In our guns. We bail out banks but reparations for generations of damage is just not “a real thing.” I know that language changes by use, mostly in the mouth of the underclass, but I wonder if a book can be a new mouth and lips to re-make a word’s intention on this day in a culture.

If you deliberately go through the door the wrong way, many of us at once, I hear a whoosh, there’s this profound redundancy meaning we go to literature to describe states of being, of mind producing sudden and inexplicable feeling. Can a feeling go both ways. Can we hate and love. I would never argue why anyone needs poetry, but everyone can find a poem that elaborates a model responsible to their own way of thinking not so much for consolation as confirmation—it bestows on you a gestational feeling like it birthed you and you feel like you did it. It’s your double. What author has not had that feeling when they meet a reader and they smile at you like you are them. Yikes. It is so violating. And yet aesthetics will not protect you. You are not alone when someone thinks they can see your mind. Reading is a collaborative act. It takes away the once-ness of the world and gives it back repeatedly. And language is the loss that repairs.

Sallie gave me her old battered copy of Sei Shōnagon. It felt precious. I had heard of The Pillow Book for years. I figured it was too feminine for me. Turns out Warhol is a copy of her. Her lists beautiful redolent lists are so unlike her flip side Huysmans, who isn’t saying what he likes (or dislikes) or notices so much as what he’s covetously explored. It’s a masculine tack & it’s just not pathetic at all.

Masculinity being a cage that feels just great about itself.

And because that’s true, Bob Flanagan crawls in one literally and spends a weekend in there trying to eat shit.

Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy is in here since he’s going back and forth through the door of gender perpetually. He’s formally pathetic—the famous black page sentimentalizes his friend Yorick’s death but then he does a little shimmy on the ole masculine contempt for women in lieu of what would more likely be a gray page, his absolute disinterest. He likes men.

I taught a Pathetic Literature seminar at UCSD in 2006 and we read Kevin Killian and Dodie Bellamy, Can Xue and Delany among others. Walser of course. We even had a pathetic conference. It was a late-night event, scantily attended. Chris Kraus came and I screened a wretched print of Warhol’s “I, a Man” with Valerie Solanas and it was so dark we really couldn’t see it at all. The sound was bad too. We had a pathetic panel and I’m sure I talked about foam. It would be my obsession for the next ten years because every book we read in the pathetic seminar had some left over froth in it. Like the action in all these novels and poems exceeded their own frame—some sludge sat right there on the water, there was spit on the corner of the boy’s mouth—you know how anxious kids used to produce spittle in grade school.

Every act had this extra dose of froth. Like the stories were bobbing in a vast and inexplicable solution, like the squeaking sounds I just heard coming out of the pasta I was cooking tonight. I got closer with my phone to record it but then the sounds stopped. What the hell was that. It wasn’t just pasta, or literature, but something tiny, mysterious, unjustly alive.

*

[1] I got this idea from the poet Brian Teare.

__________________________________

“Introduction” is excerpted from Pathetic Literature © 2022 by Eileen Myles. Reprinted with the permission of the publisher, Grove Press, an imprint of Grove Atlantic, Inc. All rights reserved.

Eileen Myles

Eileen Myles (they/them) came to New York from Boston in 1974 to be a poet. Their books include For Now, I Must Be Living Twice/new and selected poems, and Chelsea Girls. Pathetic Literature, which they edited, will be out from Grove in Fall 2022. Myles has received a Guggenheim Fellowship and in 2021 was elected a member of the American Academy of Arts & Letters. They live in New York and Marfa, TX.