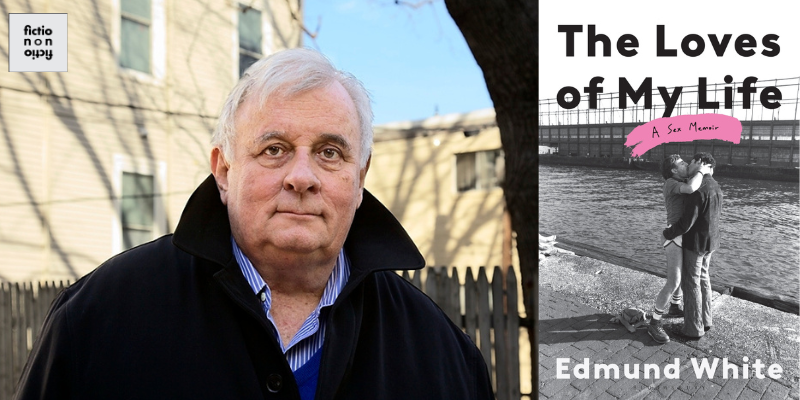

Edmund White on The Loves of My Life

In Conversation with Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan on Fiction/Non/Fiction

Novelist, memoirist and biographer Edmund White joins co-hosts Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan to talk about his recent book, The Loves of My Life: A Sex Memoir. White talks about the changes he has witnessed the LGBTQ+ community go through over the years and the hostility the transgender population faces under the Trump-Vance regime. He discusses a general concern older members of the community have about losing Social Security and health coverage should gay marriage become Trump’s next target, as well as this administration’s attempt to erase queer language from governmental archives. White previews his forthcoming novel about Louis XIV’s gay brother titled Monsieur and reads from The Loves of My Life.

Check out video excerpts from our interviews at Fiction/Non/Fiction’s YouTube Channel and our website.

*

From the episode:

Whitney Terrell: In your essay, “Pedro,” you write “For me, sex was mostly mental, an act of submission, even of humiliation, certainly not proof of virility.” This book is filled with joyous, often very funny descriptions of the physical parts of sex, but for you, where does the mental part come in?

Edmund White: Well, I think the idea of submitting to another person is more of an idea than something that you do ritualistically. Let’s say I went to bed with you. In my mind, I might be your servant, but you wouldn’t know that.

WT: So, it’s like what you imagine, or what people imagine while they’re having sex; that’s the most interesting part.

EW: I think so. I mean, it’s all interesting, but I do think that the difference between pornographic writing and the kind of sex writing that I do—I hope—is that pornographic writing is one-handed writing, and it has to not have an unusual vocabulary, and it must follow the rhythm of masturbation. The kind of writing I do is realistically about all the thoughts that go through your mind: the feeling of your leg being cramped and you’re wondering if you’re going to be able to come or not, and just all the things you think about. I mean, Henri Bergson, the French philosopher, said that the comedy begins when the body fails the spirit. So the young lovers want to run out to escape, but they can’t get through the revolving door. That is the beginning of comedy; it’s when the material world resists your spiritual ambitions.

WT: Isn’t also remembering sex part of the mental part of sex.

EW: Yes! I think there are four different quadrants of masturbation. For instance, some people are visual and other people are verbal, in other words they want to read about it rather than look at pictures. Some people want to recall actual earlier ‘hot times’ that they had, and other people want to fantasize about new ones. So I think everybody falls into some mixture of those four

V.V. Ganeshananthan: This is so interesting because thinking about what you’re describing: the imaginative state of play in terms of the mental part of sex. How does that relate to the writing of this book—the revisiting of those mental and physical spaces.

WT: Was that one-handed or two-handed?

VVG: I had a more sophisticated question for the record, but let’s go with yours!

EW: I think it was more two-handed because—I’m so old, I’m impotent, I don’t even masturbate anymore—but I have a very vivid memory. It’s probably not very accurate; my sister, who has a wonderful photographic memory, tells me that I get everything wrong in my books.

WT: You don’t have to believe her. You just remember that differently.

EW: Okay good.

VVG: You focus a lot on the language surrounding queer culture, and you have an essay “Hustlers,” which references terms like ‘hillbilly hustlers,’ ‘dirt,’ ‘rough trade,’ ‘pencil meat,’ and ‘chicken hawks,’ just to mention a few, and I was wondering if you could talk a little bit more about the role language plays in celebrating and defining and even liberating the way we think about sex. Does language make us freer, and are we any better at talking about sex than we were in the 50s?

EW: Well, I think those words that you cite, and a lot of the ‘gay vocabulary,’ was a thing when people were all in the closet and they were trying to communicate to each other subtly without being too blatant about it, or it was a campy way of talking that amused gay people amongst each other but that straight people didn’t understand so well. So like, for instance, a ‘chicken hawk’ was somebody who liked young men who were called ‘chickens,’ and so there were chickens and chicken hawks. So you would say—if this is in the 1950s—you’d say, “Oh, well, he’s a terrible chicken hawk.” I mean, there were words to describe every position and vice, and it was amusing. It made us all laugh, but it was exclusive.

There’s a private language in England called Polari, which is spoken by gay people, gypsies, and by theater people, and it’s absolutely incomprehensible to other people. But when I was young, I knew how to speak it because I had a very camp English friend who was an actor and taught it to me. So ‘riah’ was hair, but it’s just hair spelled backwards, and your legs are your lollies and so on.

VVG: I guess I would maybe make a tentative argument that as queer culture has become more mainstream, you get straight people like me who are like, “Oh, I’m learning some vocabulary of queer culture!” It’s not my language, and also the borders of the community are somewhat porous; people might identify in different ways at different times of their career, but as more people understand the ways that queer language is used in different spaces, like libraries, the Trump administration is identifying words that they don’t want to be used.

EW: Like the airplane that bombed—

WT: The Enola Gay! Whose picture was removed from the archives by some idiot.

EW: There was just, I think, a sweep by machine of all words ‘gay,’ so like the airplane that bombed Japan, the Enola Gay, all references to it were removed.

WT: I think censorship like that will never work for the exact reason that we’re talking about: people will develop their own language of secret words if they’re being repressed by a government entity or by social culture.

One of the things that I love about your work, and that I find so unique is your openness about everything, about yourself, about how you felt about different people, about your body, and it’s like you’re reaching out to experience. No experience is shameful. No experience can’t be discussed. That’s what this book feels like.

EW: It’s kind of bravado. I’d say that I’m a literary exhibitionist. In real life, I’m not at all an exhibitionist, and oftentimes, like in public meetings, people will ask me these really embarrassing questions, and I turn bright red. I can write about it, but I don’t like to talk about it. Anyway, I do with you, because we’re friends.

WT: Has that always been true for you?

EW: Yeah, I think I’m kind of stuffy in real life.

Transcribed by Otter.ai. Condensed and edited by Keillan Doyle. Photograph of Edmund White by Andrew Fladeboe.

*

The Loves of My Life (2025) • The Humble Lover (2025) • Nocturnes for the King of Naples (2024) • A Previous Life (2023) • A Saint from Texas (2022) • The Unpunished Vice (2018) • The Flaneur (2015) • Inside a Pearl (2015) • Jack Holmes & His Friend (2012) • City Boy (2010) • A Boy Story (2009) • Marcel Proust – A Life (2009)

Anthologies, Foreword & Others:

The Passion of Gengoroh Tagame (2022) • A Luminous Republic (2020) ª The Stonewall Reader (2019) • Such Small Hands (2017) • The Violet Quill Club, 40 Years On – The Gay & Lesbian Review by David Bergman, January-February 2021 • Felice Picano, Champion of Gay Literature, Is Dead at 81 – The New York Times • Edmund White and Emily Temple on Literary Feuds, Social Media, and Our Appetite for Drama Fiction/Non/Fiction Season 2, Episode 4

Fiction Non Fiction

Hosted by Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan, Fiction/Non/Fiction interprets current events through the lens of literature, and features conversations with writers of all stripes, from novelists and poets to journalists and essayists.