Easy Come, Easy Go: Lan Samantha Chang on Writing, Debt, and Diamonds

“The money will come and go but you will always have a good piece of jewelry.”

“You should buy yourself a good piece of jewelry,” advised my boss and mentor, the late Irish poet Eavan Boland.

Eavan had a way of saying things that were exciting, bracing. “A thing worth doing is worth doing badly.” “The only way out is through.” I always believed her.

It was 1997 and I was 32 years old, living in a studio apartment in Menlo Park and working as a lecturer. Until this time, my resources had been sparse, and I had no comprehension of financial hygiene. I had finished college with the help of a Pell Grant, scholarships, work-study jobs, and loans. Graduating into a recession, I had impractically found the kind of publishing position in which the salary was designed to be combined with family money. I then took out loans to finance a professional degree, accruing almost $40,000 in debt before deciding to pursue writing. I paid the tuition for my MFA program by cash-advancing my credit cards.

Aside from debt payments, almost every cent I made had disappeared into food or rent, fuel to support my writing. I was consumed by anxiety over the future.

Now, at last, I had sold my first book. The fledgling stories nursed through multiple revisions, through the stress and strain of financial instability, had been miraculously parlayed into a two-book contract. I was given a check for more money than I’d ever seen. With Eavan’s approval, I used most of the advance to pay off my student loans. Next, Eavan said, it was time to buy something for Myself.

She suggested a pair of diamond earrings.

There was nothing I wanted more than a pair of diamond earrings. I wanted to be the kind of person who wore them casually, with jeans. I wanted them to sparkle in my ears, as if I were Laurie Colwin’s character Holly Sturgis, who had never needed to work a day in her life.

My rich oldest sister, whose adult finances had been the opposite of mine, arranged for me to purchase a pair of .67 carat earrings from a jeweler she knew. They were not perfect diamonds, but they sparkled almost with an iridescence. The price was $2300. I bought them in New York and flew them back to California, where I showed them to Eavan.

“Beautiful earrings, Sam,” she said.

I didn’t understood how happy I was until I put them on with a pair of blue jeans.

For two years, the earrings made me content. They worked as Eavan had implied they would, as a talisman of my accomplishment. They were meant to outlive the money from the book deal. Of course, they were not the only evidence of the deal: more significantly, I had a novel deadline to meet. After Book One was published, I had to deliver Book Two. I had never written a novel before and had chosen an unwieldy subject. When the term of my lectureship ended, I began moving state to state, living from fellowship to fellowship. With the earrings, my existence had acquired an outward-facing glamour. Thanks to Eavan, my rich sister, and the publisher’s money, I appeared a carefree person, but my writing life was again haunted by what I owed.

Thanks to Eavan, my rich sister, and the publisher’s money, I appeared a carefree person, but my writing life was again haunted by what I owed.

Around the time the novel was due, I was living in Massachusetts, less than halfway finished with the project. That year, I left to go on a long, exhausting trip.

“I don’t want bring the earrings with me, but I’m afraid to leave them sitting in the apartment,” I told my younger, sensible sister on the phone. I felt irrationally afraid that someone would break into the apartment while I was gone.

“You should put them somewhere no one else would imagine looking for them,” she said.

“What do you mean?”

She thought for a minute. “Wrap them in a piece of tinfoil and put them in the freezer. No thief would ever think of checking there.”

I went on the trip. I spent weeks visiting family and going to a writing conference. The contrast between the small, cluttered house, where I had grown up with my sisters, and the conference’s spartan campus, was noticeable. I came home dissatisfied with my own messy apartment. I began to clean.

I don’t know why I decided to go through the refrigerator. I do still recall coming across a light and unfamiliar wad of tinfoil in the freezer and tossing it into the trash. At the end of the day, I took the trash downstairs and threw it into the dumpster.

It was about twenty-four hours before I realized what I had done. Panicking, I called the sanitation department. They said the trash collectors had already come around. I was welcome to go through the landfill, but they could recommend no systematic way to search. Of course, there wasn’t one. How would it be possible to retrieve something, amid banana peels and dirty diapers, that had been deliberately disguised to look like a tiny piece of garbage?

Easy come, easy go. Hard-won, simply tossed.

I didn’t tell Eavan or my rich sister about the earrings. Losing something priceless, out of stupidity, produces in one a specific kind of shame. I stopped buying expensive things. With the help of my sensible sister, I began keeping a budget. When I finally turned in the novel, over three years after it was due, I bought a nice watch, but I hardly ever wear it. The novel was so unimaginably difficult to finish that I can’t bear to think about, much less to flaunt, the watch. The writing gods come after the complacent. “I always knew I wanted to be an author,” an old classmate said to me, after barely managing to find a home for his third book. “And I am an author. I just didn’t know how hard it would be.” Last winter, following twelve years of battling midlife’s demands in order to make the time to write, I at last finished a third novel, but I can’t think of anything to buy for myself, unless it is another pair of diamond earrings.

Eavan’s advice was sound. Writing is not a reliable source of money. The money will come and go but you will always have a good piece of jewelry.

____________________________________________________________________

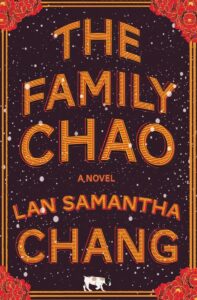

Lan Samantha Chang’s novel, The Family Chao, is available now via W. W. Norton & Company.

Lan Samantha Chang

Lan Samantha Chang’s new novel is The Family Chao. She lives in Iowa City.