Duty of Care: Tomas Moniz on Trauma, Healing and Houseplants

“I discovered something different through the trauma. We learn to grieve by grieving.”

I have never been able to take care of houseplants. I’ve always been envious of those who can nurture a baby plant, some suckling sprout or wispy, delicate little thing and coax such life.

A friend told me to start with Dracaena trifasciata—or in the more common parlance: Mother in Law’s Tongue, commonly considered one of the easiest plants to care for—and yes, even that plant I failed, burning the edges a crispy brown after a month or so in my care.

Then, after a Spring weekend retreat in the redwoods, where I wandered through hundreds of various Californisa ferns: Athyrium filix-femina (the lady fern) and Polystichum munitum (the Western sword fern), I discovered in a second-hand bookstore in Santa Rosa: Plantcraft published in 1973 with all its hippy wisdom and hand drawn illustrations; right there, I vowed to learn the art of fern husbandry.

*

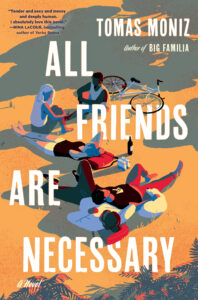

In the summer 2017, I began my novel All Friends Are Necessary as a story of friendship and intimacy between men. I wanted to craft a novel that was playful and silly and dirty because in my two previous non-fiction books Rad Dad and Rad Families, I wrote with an intensity and a seriousness, trying to push back on toxic masculinity, to highlight the complexity of contemporary fatherhood, to counter the ever present Adam Sandler trope of bumbling grumpy men discovering they could—to their shock—be gentle and kind and caring; they could be human, and still save the day.

When you’re lost in your head, do something with your hands. Or perhaps even: when you’re in pain, take care of something.

So with All Friends Are Necessary, I shifted my writing focus to celebrating friendships and hook-ups and biking city streets and skinny-dipping, all those less serious though no less important and meaningful and intense subjects that made me smile and laugh.

Oh, and music.

In the first iteration, the story came with a Spotify playlist full of ’70s metal and ’80s pop punk.

But books, like life, never end where they start.

*

In the terrible year of 2020, I suddenly longed for a savior like Adam Sandler to come take this all away because my God how could we survive all this trauma: the pandemic and subsequent anxiety at just moving through the world, the unrelenting presence of white supremacy, its visibility and violence and maleness. And here in California, the ravaging of the environment by our global climate crisis, the deadly forest fires and toxic air quality.

But what I’m really trying to name is the sudden death of my daughter-in-law five months after the birth of her first child.

My son’s first born.

My grandchild.

What I’m really trying to face is the anger and guilt and utter sadness that accompanies the unexplainable, the senseless, the tragic.

How to have all those feelings while holding my son as he navigates his own anger and loss, as he comes to terms with being a widower at 30 and a single parent of a newborn.

*

I wish I could remember who taught me this: I imagine a lover, but maybe it was a parent, even a mentor, because it’s so applicable and now seems so obvious:

When you’re stuck, help someone else.

Or to put it another way: when you’re lost in your head, do something with your hands. Or perhaps even: when you’re in pain, take care of something.

So, I did. I filled my house with plants.

I loved them all. Gave them names. Bought mostly second hand pots, but also a couple cool hipstery ones because—ugh, how cute: handmade and painted and imperfect and beautiful.

The plants greeted me each day I returned home from teaching or caring for my grandchild or helping my son or seeing my partner. I worked through my sadness as my Rubber plant (or Ficus ruby) taught me to pay attention, to discover the spot with the best light that would help them thrive. I apologized to my poor Pothos plant when I noticed how it appeared wilty and under-watered. I placed my Staghorn Fern on a bookshelf with lots of indirect light, watched how my Prayer Plant’s leaves rose in supplication each evening, adored my Monstera deliciosa as its chartreuse green petals unrolled a little bit more each day towards the window in my room.

*

We all developed a routine to help my son get through those first couple years: his sister or his mother or grandmother or me or his friends would spend time with him and the baby taking walks or reading books or singing songs while another person: his sister or his mother or grandmother or me or his friends would help with the chores, the meal prep, the laundry, god so much laundry. We were all grieving in our own ways: sometimes tears, sometimes silence and seething anger, sometimes sharing silly stories, but we did it together.

Because in the midst of all that darkness, there was a child, her energy and laughter, the work of rocking an infant to sleep, of singing lullabies, of endless walks around the neighborhood, of meal trains, of people showing up, cleaning dishes, buying groceries.

*

When I was able to return to writing my novel, one of the first lines I wrote was: mourning is a thing no one really teaches you how to do.

It’s a line that comes at the end of the book but it’s the central theme I explored over and over. I didn’t realize how little I knew about healing, blindly believing that it just happened, you put your mind to it, you got better, and then it was behind you.

Sometimes things thrived, sometimes things didn’t make it. And that was okay.

But I discovered something different through the trauma. We learn to grieve by grieving.

What I’m trying to share with you is this: in time, my Monstera deliciosa grew wild and full.

*

Eventually as time passed and my grandchild turned two, we would hike through Dimond Park looking for adventure. Once we discovered someone had destroyed a San Marcos cactus. My grandchild helped me gather the broken pieces (watch out for the pokie parts!) and we replanted them right where they were.

Recently, we strolled through my neighborhood in East Oakland. I collected various plant clippings. She held them in wet paper towels. At home, we placed them in a Mason jar of water and hoped roots would appear.

Sometimes things thrived, sometimes things didn’t make it.

And that was okay.

*

All Friends Are Necessary evolved into a novel about how we heal from loss, how we need each other, how we can redefine or remake our lives again. Here’s how I described the book: The main character, a queer Latino in his late 30s, reeling from a loss of child—and the subsequent unraveling of his job and marriage—returns home to the Bay Area during the turbulent summer of 2017 with Trump’s ascendency and Nazis rallying in the streets. The book explores the possibility of healing as Covid hits, lovers come and go, quarantine pets emerge, but, in the end, family and friends remain, a story celebrating the resilience and tenacity of friendship.

But really it’s about houseplants and springtime.

About Fiddle Leaf Fig thriving and your mother in law’s tongue getting burnt at the edges.

About grandchildren and Raffi lullabies. And Black Sabbath and The Go-Go’s.

And joy. Such joy.

__________________________________

All Friends Are Necessary by Tomas Moniz is available from Algonquin Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Tomas Moniz

Tomas Moniz is a Latinx writer living in Oakland, CA. His debut novel, Big Familia, was a finalist for the 2020 PEN/Hemingway, the LAMBDA, and the Foreward Indies Awards. He edited the popular Rad Dad and Rad Families anthologies. He is the recipient of the prestigious SF Literary Arts Foundation’s 2016 Award and the 2020 Artist Affiliate for Headlands Center for Arts. He currently teaches at Berkeley City College and the Antioch MFA program.