During World War II, Literature Reigned Supreme

How Displacement and Migration Created an Unexpected Literary Boom

One of the first writers to emerge from World War II was Gore Vidal, whose debut novel, Williwaw (1946), drew on his experience as a naval officer in the Aleutian Islands. It was a surprise bestseller, and after his second novel, In a Yellow Wood, came out the next year he found himself “very much on view with the other young lions of the second postwar generation. Journalists were eager to know if we would be ‘lost,’ too.” The magazine Life featured several of these “young lions,” including a sultry full-page photo of Truman Capote. “Thus began his career as a celebrity,” in Vidal’s words. He was 21; Vidal, 20. “In those days works of literature were often popular,” he reminisced in his 1995 memoir, “something no longer possible.”

Vidal moved to Paris in the late 1940s and stayed in the hotel where Sartre and de Beauvoir held court after they’d been driven from the Café Flore by hordes of tourists who came to look at them. “Now,” Vidal continued, “I find it hard to believe that I once lived in a time when writers were world figures because of what they wrote, and that their ideas were known even to the vast perennial majority that never reads. . . . [W]riting was still central to the culture if not the culture.” In the 1940s, literature mattered.

Popular radio shows featured literary critics talking about recent poetry and fiction. The New Yorker’s book-review editor hosted one of the most popular radio shows in America, and his anthology, Reading I’ve Liked, ranked seventh on the bestseller list for nonfiction in 1941. At the Democratic Primary Convention in 1948, F. O. Matthiessen, a professor of American literature, delivered a nominating speech for Henry Wallace, the late FDR’s vice president. Writers were celebrities. Literature was popular. The 1940s was the most intensely literary decade in American history, perhaps in world history.

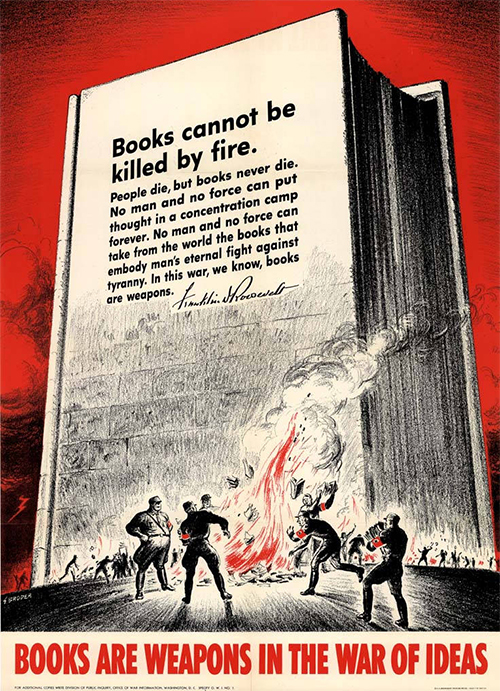

Books symbolized freedom. Posters of 1942 quoted the president: “Books cannot be killed by fire. People die, but books never die. No man and no force can put thought in a concentration camp forever. No man and no force can take from the world the books that embody man’s eternal fight against tyranny. In this war, we know, books are weapons.” During the Blitz, Muriel Rukeyser recalled, “newspapers in America carried full-page advertisements for The Oxford Book of English Verse, announced as ‘all that is imperishable of England.’” For the first and only time in history, protecting books in war zones became an official aim of armed forces.

The Writers’ War Board, founded two weeks after Pearl Harbor as an independent propaganda agency, spotlighted modernist books as the targets of Nazism. American publishers gladly joined the crusade. To buy a book, particularly a “modern” book, was to defend liberty. “This book, like all books,” read the back of the dust jacket to Muriel Rukeyser’s volume of antifascist poetry Beast in View (1944), “is a symbol of the liberty and the freedom for which we fight. You, as a reader of books, can do your share in the desperate battle to protect those liberties—Buy War Bonds.” The front of the dust jacket featured an abstract rendering of the inside of a rifle barrel.

“The 1940s was the most intensely literary decade in American history, perhaps in world history.”

The growing popularity of literature in the United States coincided with its rising international prestige. The evisceration of literary publishing on the continent and the duress of Great Britain were not all: refugees from fascism across Europe helped make New York the cultural crucible of the midcentury. Refugees from the Soviet Union were soon to follow. But American writing also gained from its embrace by European trendsetters like Sartre, who wrote in an essay published in the Atlantic Monthly in 1946: “The greatest literary development in France between 1929 and 1939 was the discovery of Faulkner, Dos Passos, Hemingway, Caldwell, and Steinbeck. . . At once, for thousands of young intellectuals the American novel took its place together with jazz and the movies, among the best of the importations from the United States.” During the Nazi occupation, reading Hemingway became a sign of resistance in itself.

According to Sartre, French writers subsequently experimented with the new American narrative techniques, revolutionizing the existing forms of French literature, which they found inadequate to the contemporary situation. French existentialist novels in turn became major influences on postwar American writing. In China, too, scholars attempting to construct a national literary tradition took great interest in American literature during the 1940s, beginning a translation project in 1941 that lasted until the 1950s, when the triumph of the People’s Republic put an end to the project, redirecting intellectual energies toward political writing and turning scholars away from the culture of the imperialist United States.

Alfred Kazin later reminisced about his trip to Europe in 1945 due to interest in his book On Native Grounds:

I wanted fiercely to learn Europe. It turned out that Europe was crazy to learn the latest American writers. So I went to Paris, on my first airplane ride, just before Bastille Day in 1945 to address the first postwar congress of French professors of English and American literature. . . . The French intellectuals I met didn’t know whether they loved America more than they hated it or hated it more than they loved it but either way they were obsessed with us.

One reason for this was the internationalism of American literature during the period. Many American writers were or had been expatriates or foreign correspondents; many were fluent in multiple languages and used them in their writing. American publishers actively sought out new and established authors from other countries. Writers and publishers from Europe lived in the United States to escape persecution. In 2008, the permanent secretary of the Nobel Prize Committee charged that American literary culture had become too insular and that it isolated itself from writing elsewhere. Whatever the merits of that charge, it could not have been imagined in the 1940s.

“During the Nazi occupation, reading Hemingway became a sign of resistance in itself.”

The German publishing industry had been immolated after Hitler’s seizure of power, with book banning and book burning heralding a general hegira of (especially Jewish) publishers. Some moved to Holland, France, and England in the 1930s, but when Germany attacked those countries they fled to the United States. The same was true of French publishers who were Jewish. They began by publishing translations from their earlier lists, but they also introduced new authors translated for the first time, which, as John W. Tebbell has written, set off “an unprecedented outpouring of books in the exiles’ own languages.”

Les Editions de la Maison Française was founded in 1940 to publish French authors in their own language. Frederick Ungar arrived in New York in 1940 from Vienna and published the work of Goethe, Schiller, Heine, Rilke, and others in the original German. Roy Publishers, founded in Warsaw in 1925, moved to New York in 1942; they had been one of Poland’s most important houses and the publishers in Polish of Pearl S. Buck, Sinclair Lewis, Ernest Hemingway, and the like. To the American public they brought the work of Polish and Slavic authors. L. B. Fischer of Germany came to New York by way of Stockholm; J. P. Didier of France also moved to New York in 1942.

Of greatest impact was Pantheon Books, launched in 1942 by the German refugees Helen and Kurt Wolff in partnership with the American Kyrill Schubert. In Europe, the Wolffs had published Max Brod, Kafka, Werfel, Gorky, Chekhov, and Sinclair Lewis, along with an eighty-six-volume series of avant-garde expressionist poetry. In New York they helped define European intellectual life, appealing to both refugees and Americans. Jacques Schiffrin joined them in 1943. He had founded La Bibliothèque de la Pléiade in Paris (which merged with the prestigious Éditions Gallimard) but was fired under Nazi pressure by Gallimard in 1940. Under his influence, Pantheon began publishing new books by André Gide and an edition (in French) of Camus’s L’étranger. Pantheon also started the influential Bollingen Series for books on psychology, art, and the humanities. The German-reading market was much larger than the French and was Pantheon’s larger initial target. They scoured the New York Public Library for European titles to translate into English, aiming to bring the best of European culture to American audiences.

In 1945 Schocken Books was founded in New York by Salman Schocken, a German Jew and friend of Martin Buber. He and his brother had owned one of Europe’s most successful retail empires in the 1920s, which he had to abandon in 1936. He had also founded Schocken Verlag, which was put under Nazi censorship in 1937. He arrived in New York, by way of Tel Aviv, in 1941. His main goal was to publish Jewish titles and spread Jewish studies. Among his early books were ones by Kafka and Scholem. Hannah Arendt joined as editor in 1946 (having arrived in the United States in 1941) and continued in that capacity through 1949, just when her influence on American intellectual life was reaching its peak.

One can barely come to a proximate understanding of the American literary culture in the 1940s without knowing a great deal of non-American literature, especially Russian, French, German, and British— and particularly Kafka, Dostoevsky, Koestler, Orwell, Auden, Malraux, Gide, Proust, Sartre, Camus, Mann—the list goes on. Mann’s reputation was so secure in the 1940s that Knopf felt advertising was superfluous for his books. Mann, who had come to the United States in 1938, attested that “the American public is to a large degree replacing my lost German readers.”

__________________________________

From Facing the Abyss: American Literature and Cultures in the 1940s. Used with permission of Columbia University Press. Copyright © 2018 by George Hutchinson.

George Hutchinson

George Hutchinson is the Newton C. Farr Professor of American Culture in the Department of English at Cornell University, where he also directs the John S. Knight Institute. His books include The Harlem Renaissance in Black and White (1996) and In Search of Nella Larsen: A Biography of the Color Line (2006).