Feature image Shevuan Williams. Norman, Oklahoma 2016.

Outspoken, provocative, novelist and essayist Dubravka Ugrešić died in Amsterdam on Friday, March 17th, surrounded by family and friends. She was known for her incisive critical voice, an intriguing playfulness and a commitment to the principles dictated by her position as an expatriate citizen of the Republic of World Letters, and was a vocal critic of the recent upsurge of nationalism and neo-Fascism.

She first began publishing her stories and novels in the early 1980s and was one of the stars of her generation of writers in Yugoslavia, a breakthrough postmodernist, exploring literature through the lens of literary theory—her other love. The Yugoslav wars broke out in 1991, first in Slovenia, then Croatia, then Bosnia and Herzegovina, and ultimately in Serbia and Kosovo by the end of the decade. Ugrešić took a firm stand against the growing hostilities, and despite her earlier Yugoslavia-wide popularity, the public reaction in Croatia to her anti-war position was swift and damning. This prompted her to move to the Netherlands, and from there she traveled all over the world as a speaker, teacher, writer.

Her nonfiction books American Fictionary, Culture of Lies, Thank You for Not Reading, Nobody‘s Home, Karaoke Culture, Europe in Sepia and The Age of Skin bring us a voice, angry, dark yet often very humorous, and a form, ranging back and forth between essay and story, that is uniquely her own. In both her essays and her novels and stories: Lend Me Your Character, Fording the Stream of Consciousness, Museum of Unconditional Surrender, The Ministry of Pain, Baba Yaga Laid an Egg, and, most recently, Fox, Ugrešić explores many facets of displacement, transnationalism, the joys of literature and the ramifications of living the life of a public intellectual.

She was given the Neustadt International Prize for Literature in 2016 and received prestigious awards in Austria, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Switzerland, Slovenia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Yugoslavia; she was a finalist for the Booker Prize, the Best Translated Book Award, the International Foreign Fiction Prize and the National Book Critics Circle Award. Her novels and essays have been translated into thirty languages. Her US publisher is Open Letter Books.

Here, Ugrešić’s English translators Celia Hawkesworth, Mark Thompson, David Williams, Vlad Beronja, and I remember her and her work. (Michael Heim, who translated Fording the Stream of Consciousness and The Ministry of Pain and collaborated with Celia Hawkesworth to translate the stories in the collection Life is a Fairy Tale, sadly predeceased Dubravka.)

–Ellen Elias-Bursać

____________________________________

I met Dubravka at a writers’ conference in Zagreb in the 1980s and was immediately entranced by her perceptive, humorous observations of people and the world around her. To her I must have been one of those dumpy little women in glasses she described once as having had a holiday fling in Dalmatia and who now hung around those gatherings, living off the memory by translating.

Our first joint project was Štefica Cvek, published in 1992 as In the Jaws of Life. There were hints of darker undercurrents in those days, but they seemed full of promise for the young writers then starting their careers. Later, as we worked together on translations Dubravka would come often to the UK and wistfully suggest that maybe she could settle in the summerhouse at our Oxfordshire cottage.

When we set up the Soros-financed Supplementary Grants Programme for students uprooted by the war, Dubravka agreed to join the board. Those purposeful meetings, focused on the young, were a tonic for us all. For me, working on her brilliant writings was the greatest privilege. I am forever grateful to have had the chance to share them so closely with their extraordinary, irreplaceable creator.

–Celia Hawkesworth was the first to translate Dubravka Ugrešić’s writing into English, with the novella In the Jaws of Life, then her later work Have a Nice Day, Life Is a Fairy Tale, Culture of Lies, Museum of Unconditional Surrender, Baba Yaga Laid an Egg, and Thank You for Not Reading

____________________________________

London, March 1991: meeting Dubravka to discuss her English debut, Fording the Stream of Consciousness. But Yugoslavia, on the brink, steals our time. Her viewpoint is aerial. “All the walls are destroyed, of course,” she says in her sharp unsettling way, “but the border [with Europe] still exists. More, I think, because of our side than yours.”

Zagreb, December 1992: translating her letter of resignation from the Society of Croatian Writers (formerly Society of Writers of Croatia). I sit; she paces. Did she protect her work by burning surplus outrage in talk, letters, mails? When I puzzle over someone’s swerve to nationalism, her answer sears the inbox: “I am sorry for you. You are good, nice and polite. However, you don’t know the zone you are dealing with. I was the same. It took me years to learn the ‘language’ of the people surrounding me. I am not smarter today. I just avoid contacts…”.

Oxford, June 2022: reading Danilo Kiš’s letters. A friend of his took solace in knowing Kiš was alive and “breathing somewhere. Anywhere.” I quote this to Dubravka, who says she would be happy to see us (“Do you know there is a direct train from London?”). Missing the cue, I send a book instead: Love’s Work, by Gillian Rose.

–Mark Thompson collaborated on the translation of Baba Yaga Laid an Egg with Ellen Elias-Bursać and Celia Hawkesworth

____________________________________

On the evening of Friday 17th March, I found a frog inside my front door. I almost shit myself.

That’s an impolite but very faithful translation of the experience. In New Zealand, where I live, no one I know has ever had a house visit from a frog. It wasn’t until around midday on Saturday that I received news of Dubravka’s passing. With the time difference, the frog had visited around the time of her death. I googled it. Many ancient cultures believed that frogs were messengers between the spiritual realm and the physical world. It sounds like the kind of shaggy dog story from which Dubravka would spin a good yarn. But it’s true. It happened.

One winter I stayed with Dubravka in Amsterdam. Her apartment building was a brutalist concrete structure with hundred-metre-long balconies forming lonely outdoor hallways. In her writing, Dubravka triumphed over the banality of both nationalism and late-capitalism. But she paid a terribly high price. The last time I saw her was in Zurich. She was staying in a lovely little hotel on a cobbled square. It wasn’t Geneva, but it was like something out of Three Colours Red or The Unbearable Lightness of Being. I prefer to imagine her there.

–David Williams translated Europe in Sepia and Karaoke Culture, and collaborated with Ellen Elias-Bursać on Fox

____________________________________

I hadn’t heard from Dubravka for a few weeks this February, so on March 8th, International Women’s Day, I called her to wish her well. She told me then that she was ill and had been ill for over three years. This was nine days before she died. She and I had been working closely together on translations throughout those years yet I hadn’t known. In Croatia there is a saying: hiding something like a snake hides its legs. Very Dubravka.

One of my first thoughts was how gleeful she’d been this January when we spoke over Zoom. In a translation we were working on I had misstated the title of the US television series as Buffy the Vampire Killer. Slayer, she crowed, Slayer!

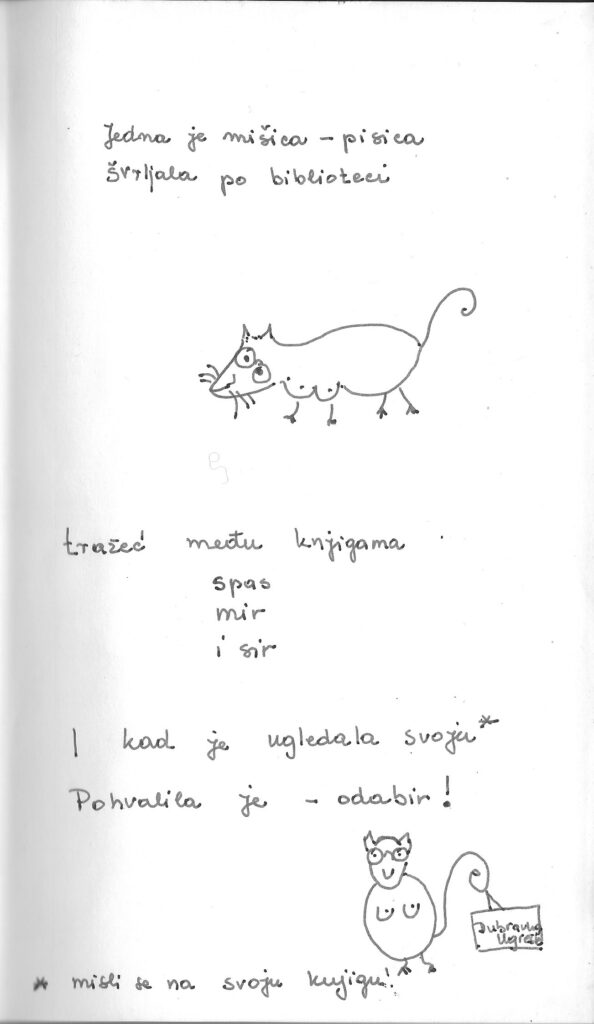

In the early 1980s, before we’d met and become lifelong friends, she stayed at my summer place in Istria when I wasn’t there, and she happened upon her Štefica on the bookshelf. She inscribed my copy—still on my shelf today—with a charming note, illustrated with a buxom spectacled little mouse and even a footnote!

A rough translation:

“A little author-mouse poked around the house, seeking

salvation

peace

and cheese

And when she saw hers* she praised—the choice!

Dubravka Ugrešić

*meaning her book!”

–Ellen Elias-Bursać translated Nobody‘s Home, The Age of Skin and A Muzzle for Witches, and collaborated on the translation of Fox with David Williams, and on Baba Yaga Laid an Egg with Mark Thompson, and Celia Hawkesworth

____________________________________

For many of us who had left the disintegrating Yugoslavia in the 1990s, “like rats deserting a sinking ship,” with barely a tote bag or suitcase in hand—Dubravka was the poet of our newfound and embittered worldliness and the literary alchemist of our fragile memories. Since then, many of us have acquired new lives, new languages, new passports.

Some of us have even stopped thinking of ourselves as refugees altogether, buckling under the pressure of assimilation to secure our daily bread under a different sky. But with each new book, Dubravka reminded us again of that formative experience of migration, that dioptric of enduring alienation that no new passport can fully correct. And it is this defamiliarizing way of seeing the world from the margins that runs like a bright red, revolutionary thread throughout her virtuosic literary oeuvre.

The numerous prizes and the periodic Nobel buzz aside, in her socially subversive imagination, Dubravka saw a profound affinity between her own literary labor and the circus acts of a Polish housecleaner in Amsterdam, the woeful busking of a Romani woman in Berlin, the meticulous work of a Vietnamese nail technician in New York—all precarious figures, all migrants, perennially exposed to the cruel whims of the capitalist marketplace.

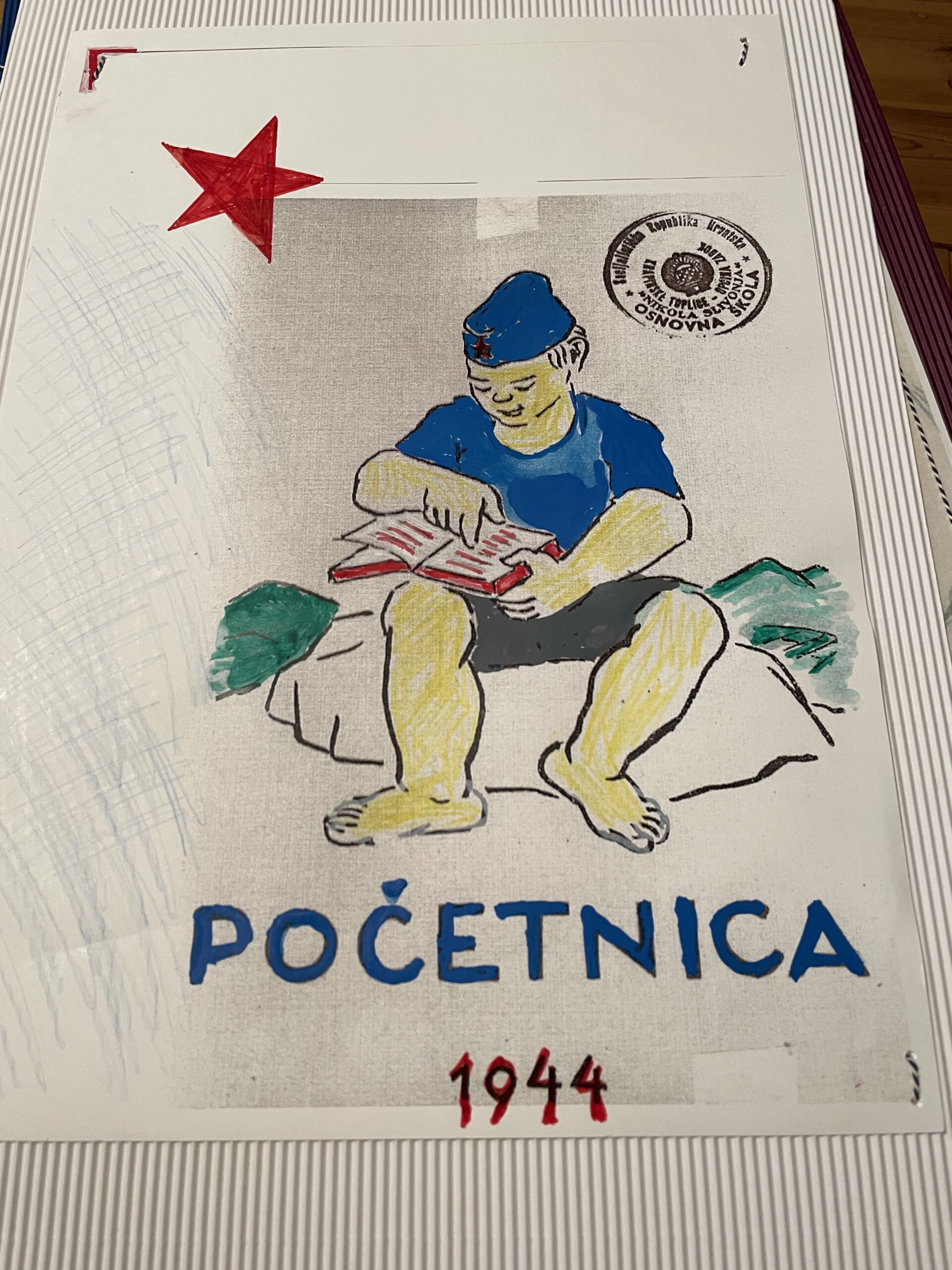

I am including two of Dubravka Ugrešić’s late collages, which she was working on to the very end and sent me not even a month ago. The caption that she provided for one of them was “Lenin and Lolitesa.”

–Vlad Beronja translated The Red School