Dreams of Liberation: Alex Zamalin on the Political Power of American Countercultures

The Author of “Counterculture” in Conversation with Aaron Robertson

What is a counterculture, and what impact has it had on U.S. society and politics? Why do countercultures form, and why do they rise and fall? At a moment when today’s youth feel a sense of despair about humanity’s future, can counterculture offer us a roadmap for a liberatory politics?

In this conversation, author Aaron Robertson (The Black Utopians, FSG, 2024) talks to Alex Zamalin about his new book, Counterculture: The Story of America from Bohemia to Hip-Hop (Beacon Press) which tries to answer some of these questions.

*

AR: Your definition of the American counterculture hinges on the idea of “revolutionary freedom.” Can you explain what that means to you, and how you came to center that idea in the book?

AZ: As I began writing the book, I tried to understand what is about the counterculture that draws people in, at least initially. As someone who grew up in the 1990s—listening to hip hop, grunge, and, later, being part of the punk scene in college—I had an intimate relationship with countercultural movements, and very powerful feelings about them.

And yet, as I began to think about what it was that drew me in to these movements, and made want to be part of them, the thing I circled around was the feeling of freedom. When I say feeling, I mean it in precisely that way. The feeling of freedom. What does it feel to be free? What are the sights, tastes and sounds of freedom? What is the experience of freedom like?

This, I should add, doesn’t fall into the traditional understanding of freedom. Political theorists, historically, have advanced two types of freedom—”negative freedom,” to do what you want as long as it doesn’t infringe upon others to do what they want, and “positive freedom,” which is about having the resources to be able to do what it is that you want.

Neither of these classic definitions, however, captures the powerful feeling of self-reinvention, motion, transformation, or presence that the counterculture inspires and embodies.

I chose the term “revolutionary freedom” because I think it usefully captures the sensations of being part of something that transforms who you are, and has the potential to transform the world.

When I began to think about this aspect of freedom found in the counterculture, I wanted to stress how it had a different texture. I chose the term “revolutionary freedom” because I think it usefully captures the sensations of being part of something that transforms who you are, and has the potential to transform the world. To love, feel, think, move and desire in whatever way you want: this kind of freedom.

The counterculture invokes this kind of freedom. What is more striking, perhaps, is that it tries to do this at two levels. There is individual freedom, but there is also the collective, political level of freedom. I think the attempt to combine the two is what makes countercultural movements so unique—and why I think their account of freedom is revolutionary.

The counterculture genuinely believes that transformative personal feelings could, and should, be part of collective life, of the experience of being in common with others. And the reason this is striking is collective life is, often, at odds with such expressions of freedom.

There’s this ongoing tension between the counterculture which says “yes” and society which says “no,”—whether we are thinking about free speech, sexual desire, creative expression, and so on. And yet, the counterculture continues to carve out a space for itself to be able to model its version of freedom, despite the pressure and hostility from the mainstream.

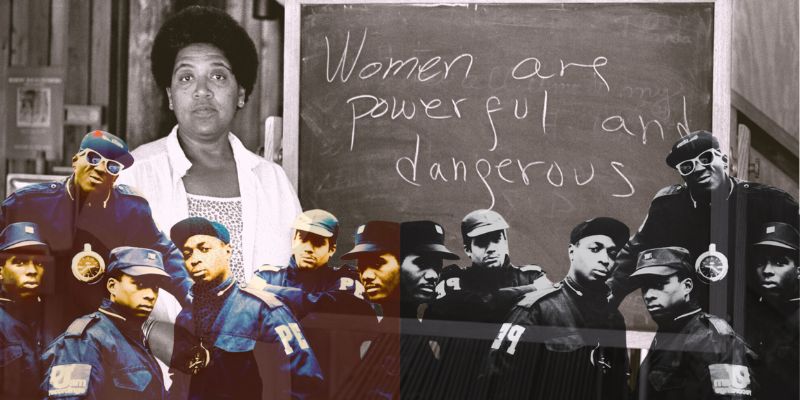

AR: You beautifully trace various countercultural lineages throughout the book—beginning with Walt Whitman in a rapidly transforming country and taking us all the way to Spike Lee, Basquiat, and N.W.A. Take us behind the scenes—how did you think about the arc of this book when you began writing?

AZ: I really wanted to express the depth and breadth of counterculture over time. Normally, when we think about “counterculture” we think about the 1960s. This has a lot to do with the fact that the term itself was popularized by Theodore Roszak in his 1969 book, The Making of a Counterculture: Reflections on the Technocratic Society and its Youthful Opposition, which chronicled the prominent youth movements of the time—feminist, Civil Rights, antiwar, and hippie.

But I also think the focus on the 60s has to do with the fact that our official language of thinking about “opposition to the mainstream” is still hopelessly mired in the 60s. There’s still a kind of romanticization of that period, where the paradigm of postwar America fundamentally shifted—when it comes to race, gender, sex and war. I wanted to take us back to earlier and later periods of countercultural dissent to shift our perspective from the 60s, and, ultimately, to move past the its romance.

For example, Walt Whitman—this revered American poet, who is canonized in public school—was a queer bohemian who championed radical democracy, the working class and was antislavery (but was also a garden variety antiblack racist of his time, a hustler, self-promoter, personal brand manager, and provocateur).

Or, that such important cultural figures like Langston Hughes, Allen Ginsburg, and Audre Lorde were not all-knowing, or self-assured, but, to the contrary, suffered from extreme self-doubt about their place in the world and about their ideas about it.

Or, that the members of Hip Hop group, Public Enemy, in the 1990s—this in your face, radical Black nationalist group—whose song, “Fight the Power,” was an anthem for resistance—saw Martin Luther King, Jr., and his vision of nonviolent civil disobedience, as an inspiration for their art and politics.

When you look at counterculture through the long arc of history beyond the 60s, you notice the contradictions and paradoxes of counterculture. When viewed in this light and from this perspective, I think, the counterculture becomes more human, and much more interesting.

You have these contradictory people struggling to articulate utopian images of the world, as the world in which they live pushes hard against these images. How does one continue to maintain hope in such a scenario? Continue to speak with conviction?

The longer the historical arc of counterculture the more diverse and more complicated in appears. And, as a result, its most prominent figures no longer feel like deities to be worshipped. Once this shift happens, it places greater responsibility on us in the present.

If the counterculture, for instance, never “had it all figured out” as the word was marked by profound structures of domination in their time—slavery, war, genocide, exploitation, environmental collapse—then it means they were, in a certain sense, in a condition that many of us experience today—we, who are struggling to articulate visions of freedom in a world marked by despair, hopelessness, nihilism and the threat of impending catastrophe.

Learning from their stories is a good way to help us navigate our present.

AR: Your countercultural figure isn’t just one thing—she contains multitudes. You write about free-thinkers, populists and anarchists, psychoanalysts and intersectional feminists, abolitionists and gangsta rappers. Was there a single figure among these with whom you connected most powerfully, perhaps through the research process? I know Amiri Baraka was a big influence, but I’m especially curious about a lesser-known figure.

AZ: A figure I knew nothing about, who I also found to be fascinating, was Bruce Nugent. Standing six feet tall, and known for wearing second-hand suits, Nugent was an openly and unapologetically queer Black writer during the Harlem Renaissance in the 1920s—he was a close friend of Langston Hughes and was involved with the short-lived radical magazine called, Fire!!, which published its single issue in 1926, and which featured work from luminaries Aaron Douglas, Zora Neale Hurston and Langston Hughes, before they were household names.

Nugent, along with the editor of Fire!!, Wallace Thurman—a queer Black man from Utah—would be well-known for their house parties at 267 West 136th Street, which they ironically dubbed “Niggerati Manor.” The walls of their apartment were painted red and black, and, among other things, had large murals of painted phalluses. This was the center of the Harlem Renaissance, which captured the movement’s radical politics and queer impulses.

Queer men and women were a visible part of Harlem counterculture, where they were regulars at cabarets, tenement parties, and speakeasies. The Hamilton Lodge Ball at the Rockland Palace Casino, the most popular masquerade and drag ball at the time, was attended by many of Harlem’s luminaries.

Yet when we think about the Harlem Renaissance today, we, think about it in a way it never imagined itself: through the idea of respectability. Bruce Nugent and Wallace Thurman are forgotten, and Fire!! is barely mentioned. If anything, figures like Langston Hughes (who was always ambiguous about his sexuality) and Zora Neale Hurston (who bristled at the very idea of respectability) are put forward as examples of Black genius and literary merit—to include them into the literary canon of American culture.

This, rather than seeing them as radical young artists struggling to make ends meet and building community, who fundamentally transformed American society. Now, this fact in itself isn’t surprising, given that countercultures are always coopted, and sanitized by the mainstream.

What I think is quite striking is that an intersectional movement—Black and queer—that imagined itself as such, and did so openly and clearly, is hardly acknowledged as such, and rarely taken as an important predecessor to many movements we see today. Despite its hundred-year anniversary, the Harlem Renaissance, still remains underexamined and misunderstood for its cultural impact.

AR: You pay special attention to the physical spaces that defined various countercultural eras—the Pfaff’s beer salon in New York City, for example, or Sach’s Café, where Emma Goldman met Alexander Berkman. Why did you want to write about these kinds of places?

AZ: As a writer, I want to get a sense of how ideas unfold. To me, the specific places where ideas happen is crucial for understanding them.

In politics, we know the usual spaces—the Lincoln memorial, the street, the town square, etc.—but the counterculture also has its own spaces—the bar, the club, or the coffee house. These spaces are unique because they provide a space for people to come together, but they also exhibit the kind of utopian world which its members want to inhabit.

It’s one thing to talk about something, or to read something. It’s another thing to be part of a physical space, where you feel things viscerally. A smoke-filled bar, a club with deafening music, an abandoned warehouse transformed into an art space. These spaces themselves affect how we might think about equality, justice or democracy.

There’s a quote that I draw on in the book from the Black socialist Chandler Owen, who, in the 1920s, called the cabaret “the most democratic institution.” It’s fascinating to compare this idea with Ancient Greek conceptions of the agora—the town square—where theorists like Socrates, Plato and Aristotle imagined democracy through the hustle and bustle of city life.

For Owen, the fact that the cabaret exists underground and out of sight makes it the most democratic because it is only there where marginalized peoples can express their identities and engage in self-determination. Whereas for the Ancient Greeks, in contrast, democracy must always be a public act for everyone to see. And yet, in many ways, it is in private countercultural spaces where political reflection first takes place for many young people.

I remember when I was in college, during the Iraq War, the Bush years and post 9/11 America, and I went to my first punk rock show in a cramped basement. Then, I had a vague understanding of politics, but there was something about the rage and irreverence expressed in punk music (and specifically, the feeling of being in the space of a basement, underground) that gave me a language to develop a critical orientation toward the world.

AR: You’re careful not to romanticize the figures you write about. Walt Whitman held racist views. Jean Toomer didn’t pay back someone who loaned him a lot of money. Nella Larsen was embroiled in a ruinous plagiarism scandal. Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg thought the “Beat aesthetic” was decidedly male. And so many movements were eventually co-opted by capitalist structures.

Why was it important for you to show the unseemly sides of American countercultures?

AZ: Countercultures are oppositional to the mainstream culture, but they also emerge from that culture. This is an important lesson not only for understanding the counterculture, but for understanding all cultural movements—especially radical ones that try to oppose and topple the status quo.

Clearly, the backlash exists only because the threat of transformation appears real.

To deny this fact is to engage in a profound misunderstanding of how culture, in any form, works; to refuse to learn from this process is, I would argue, even worse, because it represents an important opportunity for reflection and critical engagement.

Today, when we are having discussions about who and what content to “cancel” and what “free speech” might look like, we are often missing the broader question of what it means to cancel, or oppose, certain reactionary ideologies that are smuggled into certain frameworks. Not just racism, sexism, homophobia, classism, and so on, but instrumentalism, objectification, thoughtlessness, amoralism, and cruelty.

Looking at the unseemly side of counterculture gives us a perfect way to explore how and why movements that claim to be against certain ideals end up reproducing them in their own work.

AR: After reading Philip Gura’s book American Transcendentalism: A History a few years ago, I sort of became convinced that the members of the Transcendental Club created the most enduring countercultural movement in our country. Where do you come down on the Transcendentalists and their influence on American culture? Do you see its manifestations today?

AZ: Nineteenth century Transcendentalism (the figures here are Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Margaret Fuller, Amos Alcott and, to a lesser extent, Walt Whitman) is, arguably, the first major countercultural movement in the U.S. to have received national attention.

Part of this certainly has to do with the fact that these figures were well-respected authors and public figures who argued passionately against the status quo (they were antislavery, feminist, reform-minded at a time when these positions were controversial), but also because their doctrine of radical individualism was, and still is, suitable for a nation that imagines itself as exceptionally committed to freedom.

So, to answer your question, yes, Transcendentalism remains widely influential in American culture (we see it in the various appeals to self-invention on social media, its influence on DIY culture, the use of irony, and iconoclastic and rebellious expression in the youth).

Indeed, without Transcendentalism and its artistic call for creative and spiritual personal rebellion it would be hard to imagine the counterculture existing in the U.S. (many figures cite Emerson and Whitman as important influences). But part of what accounts for this ongoing influence, I think, is that Transcendentalism, more so than other counterculture movements, remains trapped within the firm boundaries of American exceptionalism.

It’s important to remind readers that the Transcendentalists, for example, despite writing at the same time as Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, and witnessing the revolutionary anticapitalist, socialist upheavals in Europe—given their commitment to individual freedom, never went so far as to argue for socialism. Transcendentalists were antislavery, but not always racially egalitarian, or advocates of Black liberation.

In many ways, they represented something a safe, or contained, resistance to American culture, that went just far enough to scandalize the mainstream, but never farther than that. So, there’s a paradox with Transcendentalism. Its influence depends on its ability to reaffirm American individualism, just as its radical practice has the capacity to transform America itself.

AR: You end the book with reflections on some of the temporary autonomous zones that cropped up around the country in the wake of the protests for racial justice in 2020, including the Capitol Hill Occupied Protest (CHOP) in Seattle. I’m curious if other countercultural figures or experiments since then have been noteworthy in your eyes? Was 2020 a turning point, for better or worse, for American countercultures?

AZ: Despite the temptation to make a definitive statement, especially given the right-wing shift since 2020, I think it’s still early to tell. But what we can say, for sure, is that these countercultural movements did have a profound impact on the culture.

The very fact that we talk about “being woke,” or that the ongoing right-wing backlash to 2020 is so hell-bent on attacking DEI and what it calls “Marxist” ideology, or “transgenderism,” is an indication that the counterculture has, in a certain way, shifted the public discourse remarkably. At the same time, the recent backlash isn’t new; it is to be expected.

In the 1970s, Richard Nixon came to power through his promise to crush the lawlessness he saw with the student movements, just like Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush in the 1980s campaigned on a return to traditional family values, they thought were being eroded by a burgeoning queer culture.

Clearly, the backlash exists only because the threat of transformation appears real. As always, the question, however, now and then, remains to what extent counterculture discourse becomes solidified into a formidable politics.

To what extent will 2020’s most radical ideas—defunding the police, prison abolition, socialism—disappear as a result of the backlash, or to what extent will they be reimagined? We could be living through a brief period or reaction, or something else, entirely.

The point to stress is that countercultural movements are not helpless in the face of changing political and historical conditions. It is partly on them to decide how to respond, and to ensure that their most transformative impulses aren’t forgotten.

______________________________

Counterculture: The Story of America from Bohemia to Hip-hop by Alex Zamalin is available via Beacon Press.

Aaron Robertson

Aaron Robertson has written for The New York Times, The Nation, Foreign Policy, and elsewhere. His translation of Igiaba Scego's novel Beyond Babylon (Two Lines Press, 2019) was shortlisted for the PEN Translation Prize and Best Translated Book Award.