Dreams Are Serious Business: On the Dangers of a Fertile Fantasy Life

Robin Yeatman Considers the Intersections of Inner Death, Destructive Dreams, and Fiction

As long as it’s limited to an “inside voice,” most would agree that indulging in flights of fancy is harmless. What happens in fantasy stays in fantasy, right?

At best, fantasy provides a much-needed change of scenery. At worst, it’s a guilty pleasure, contained in the privacy of our deepest, darkest thoughts. What harm can it possibly do? An elaborate revenge scenario or thrilling romantic encounter that is limited to the imagination serves only to provide solace or excitement to the person imagining. That’s why we all do it.

Literature, however, tells us otherwise: fantasy has tangible, and often fatal, repercussions. Dreams are a serious business, as it turns out. They can be the seed of a strangling vine. The rehearsal for a serious act. The ideal that distorts the real. Writers return to the subject of fantasy over and over, dramatizing the destruction that can occur when deep-seated dreams fail to match reality.

And there are plenty of fictional characters with fertile fantasy lives. Emma, in Flaubert’s Madame Bovary, operates out of a powerful desire for luxury and romance, a fantasy inspired by novels she’s read. This fantasy is so seductive, it leads to not only her own tragic fate, but also that of her husband, who dies broken-hearted and penniless, and daughter, who ends up a laborer in a cotton mill and relying upon impoverished relations for shelter.

Literature, however, tells us otherwise: fantasy has tangible, and often fatal, repercussions. Dreams are a serious business, as it turns out.

Similarly, in Richard Yates’ novel Revolutionary Road, the fantasy of a reinvented life in Paris for married couple Frank and April Wheeler lifts them up and out of the banality of American suburbia. Envisioning freedom and intellectual superiority, the couple temporarily mends their toxic marriage. When the fantasy is dashed by an unexpected pregnancy, so are they, in every sense of the word.

In Carson McCullers’ The Member of the Wedding, Frankie, a lonely twelve-year-old girl, imagines a life of belonging and acceptance, all hinging on her brother’s upcoming wedding. Surely, she imagines, he and his bride will include her in their new and beautiful life. She will leave the hopeless life she now leads, to be an important and beloved member of a trio. With all her energy invested in the upcoming nuptials, the fantasy takes over. She never once considers the possibility that she will return to her father’s gloomy house after the ceremony. It’s a very rude awakening, when the anesthetic of fantasy wears off.

Maybe the fantasy life of a fictional character has never been quite so strongly represented as in Patricia Highsmith’s 1965 novel, A Suspension of Mercy. My eyes bugged out of my head when I read about Sydney Bartleby, a young American writer who constantly ideates the violent death of people around him, but mainly that of his wife, Alicia:

Alex had died five times at least in Sydney’s imagination. Alicia twenty times. She had died in a burning car, in a wrecked car, in the woods throttled by person or persons unknown, died falling down the stairs at home, drowned in her bath, died falling out the upstairs window while trying to rescue a bird in the eaves drain, died from poisoning that would leave no trace.

He thinks on it so much, he lives it. Though he doesn’t actually touch a hair on her head, he behaves as though he has. He makes callous jokes to his writing partner. He buries a rolled-up carpet in the woods in the very early hours of the morning. He writes incriminating diary entries. All of that is fun and games until Alicia goes away without telling anyone where, or when she will be back.

A character’s strong fantasy life can’t help but affect—or is it infect?—their real life. At first, Sydney thrives in Alicia’s absence. He enjoys bachelorhood, and his writing takes off. He sells a television serial and that pesky second novel that he’s been tinkering with for years. He doesn’t miss married life, or the little barbed comments Alicia was prone to make. He doesn’t pretend to, either. He does, however, continue the fantasy of the murdering husband.

He could easily make all the problems go away by telling the truth to the police. But what, then, would happen? His life would go back to the way it was. Harsh reality would return—Alicia back home, bickering resumed, that trapped feeling brought on by their mis-matched relationship. Even with the police on his tail, the possibility of permanently staining his good name and worse, Sydney prefers to continue the fantasy, stretch it out long and taut, right to its breaking point.

Readers are apt to identify the most with characters prone to imaginary flights. After all, reading itself is a form of fantasy life.

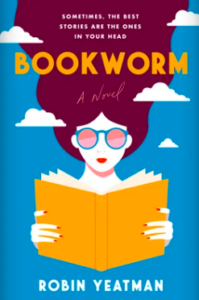

Readers are apt to identify the most with characters prone to imaginary flights. After all, reading itself is a form of fantasy life. How better can we immerse ourselves so deeply in another experience, thus removing ourselves from our own, one chapter at a time? In my own novel, Bookworm, the protagonist Victoria, a woman who feels profoundly trapped and misunderstood, self-soothes by toggling between plotlines of books she’s read and her own dark fantasies. For Victoria’s case, as for Sydney’s, fantasy bleeds inexorably into reality.

Fantasy is an archetypal psychological tool people have long used in order to escape the pain of the everyday. Authors reveal their characters’ fantasies to inform readers of these pains, and show us the dramatic and destructive outcomes when the fantasies are not realized.

Unrealized dreams won’t all end in murder, as in a Patricia Highsmith novel, but an inner death is experienced when our desires ultimately don’t meet our lived experience. This inner death is what writers take so seriously. It’s the silent, personal, everyday tragedy of a person’s life that writers acknowledge by exploring the topic of destructive fantasy. And it’s a reminder too, that the inner life can be just as powerful and vital as the outer one.

We readers are lucky. Through literature, we are comforted. You aren’t the only one who wants something different from what you’ve got, writers tell us. However, we are also warned: You might not get what you want. And what happens then?

That’s not to say we should abandon our dreams, whatever they may be. It’s human nature not to give them up. Writers will never stop writing about people reaching for their (dangerous) fantasies, and we will never stop reading about them.

_____________________________

Bookworm by Robin Yeatman is available from Harper Perennial

Robin Yeatman

Robin Yeatman is a shameless bookworm born in Calgary, Alberta, and raised in Vancouver, British Columbia. Educated in Canada and England, she trained as a broadcast journalist and worked in radio for roughly a decade. After a dozen years in Montreal, she now lives in Vancouver. Bookworm is her first book.