The windows were misted up and the air thick with tobacco smoke. The coffee shop on Kungsgatan had quickly come to feel like home. Immanuel behaved like one of the regulars, nodding in recognition to the tables by the window as he stepped inside and closed the inner glass door behind him. There were always people here he recognized, many of them sitting alone with a book in front of them or a newspaper spread out on the table. At the far end of the café sat Ascher, writing. Immanuel pretended he hadn’t seen him to avoid being drawn into a conversation about how they should split assignments for Basler Nachrichten. The fact was, Immanuel felt uncomfortable with the whole situation. It was really unfortunate that Ascher had ended up in Stockholm too, after being forced to leave his post in the Vatican. No one found him a likable person. He was always the injured innocent, and often ill-tempered.

As usual the café was full. Every day small groups of people would meet, speaking languages of which Immanuel had a better command than his adopted land’s. He gleaned fragments of their stories. Two Russian men, one bearded and rather portly, the other bald and wearing high-strength spectacles, were al ways sitting deep in conversation at the same table. Now and then they would glance around, as if they were actually keeping watch on the place. There were Poles, in exile for months or years, on their way to the next city, with worn-out suitcases and leather briefcases bursting at the seams with the thick sheaves of papers inside: passports so crowded with stamps they were illegible, visas and testimonials grubby with thumbing and anxious fingering. Large numbers of German speakers were here, some of them well-dressed office workers but others stranger characters with furtive eyes, on the run or perhaps with business best kept to themselves. And then groups of Swedish women, young and all dressed up, as if they were on their way to some festive soirée, although it was early afternoon on a very gray weekday in the autumn of 1939.

He had almost an hour to read the newspapers. Rickman wasn’t due at the café until three o’clock. Bermann Fischer had asked him to get together with the Englishman. Preferably not at the publishing house but somewhere else, on neutral ground. An agreeable fellow, a man with a past in the world of musical entertainment, thoroughly charming, the publisher had assured him. The purpose of the meeting was unstated, but the publisher had implied it had something to do with deliveries to Germany and had added that his secretary Miss Stern would be pleased to assist with the practicalities.

Bermann Fischer had already given Immanuel a number of minor editorial commissions, and he naturally hoped for more. He wondered how he could broach the subject without appearing either too forward or too desperate. To show his willingness to meet with an unknown Englishman was one way of demonstrating his keenness. Unfortunately it was becoming ever clearer that he needed several sources of income. He was finding it more difficult to have his articles accepted. His work was published very infrequently in De Telegraaf now, and he didn’t understand why. When he applied for a residency permit in Sweden, he had listed the Dutch newspaper as though it were as obvious a revenue stream as Basler Nachrichten. On the other hand he hadn’t mentioned the provincial German-language newspapers where his items regularly appeared; it had been too complicated to explain the press agency’s somewhat special function in Berlin. In the long run that couldn’t be counted on as a given either. It was only a question of time before it ceased entirely. He hadn’t heard from the editor, Kutzner, for months. Nor from Ilse Stübe either, who was supposed to be the new contact person.

Immanuel sat down by one of the windows and placed his briefcase on the chair next to him and Basler Nachrichten on the table in front of him. As usual it was a two-day-old newspaper. One of his own articles, an attempt at summarizing the reactions in the Nordic countries to the outbreak of war, was at the top right corner of page 1. That was gratifying. Albert Oeri, the increasingly renowned editor in chief, had recognized the importance of a staff writer in this little metropolis in the far north, a place that until recently had been completely peripheral but now suddenly was the scene of vital decision-making. In fact it was the city in which Europe’s future might be decided this very autumn, maybe even within the next few weeks, if Immanuel had interpreted accurately the precarious situation that had developed concerning the transport of iron. If its transportation were to be disrupted in the slightest, German occupation wouldn’t be far behind. Dr. Oeri had understood this and encouraged him to write regular reports, giving his articles a prime position in the newspaper. He didn’t need to worry about Ascher. Clearly Oeri preferred Immanuel’s pieces to Ascher’s, which more often than not concerned obscure topics from the Catholic world and were generally placed near the back of the newspaper. And yet it was a difficult situation to have a rival who made no bones about his readiness to fight for space.

Immanuel’s article, the third longest from Sweden, was extremely well placed. Although the remuneration left much to be desired, this was the ultimate incentive, a validation greater than that generally bestowed by money, even if it was the money he needed at the moment more than anything else.

It had been a time of constant disruption. For a number of weeks now he and Lucia and their sons had been lodging with the Weil family in Vasastan. They had three adjacent rooms, which in reality felt like their own apartment. And furthermore, the Weil family were almost never at home. But if they were going to stay in this city for several years more, another solution would be required. Yes, he would have to talk finance with the editor. It was clear from the positioning of the articles that his cooperation was appreciated. It’s unwise to pay too much, Oeri had said the last time they met and the question of fees was raised. But thankfully he had added that paying too little could cost even more. There was clearly room for negotiation, even if he could also recall another of the Swiss journalist’s less promising axioms: Money won’t help on Judgment Day.

Judgment Day or not, vital decisions for the progress of the war would be taken by his adopted country’s government this autumn or winter. Though perhaps in the long run it would be the family of the industrial tycoon who decided, or so it sometimes seemed to anyone trying to follow the negotiations. Lagerberg had promised to arrange an audience for him with Marcus Wallenberg.

It was evident that the whole scenario could change radically over a matter of weeks. And if the Germans entered the country, what would happen then? What help would an increased fee from Basler Nachrichten be when that day came? How would they be able to leave Stockholm without a visa for any other possible country? Deportation to Germany would be equivalent to a death sentence. Perhaps the boys should stay here if flight became the only option. But the mere thought was unbearable. He had the same suffocating sensation he had experienced so often since their arrival here, an increasingly frequent reminder of the seriousness of their plight. The relative calm could end at any moment, he knew it, his body knew it. It wasn’t just the swastika in the window of the German travel agency around the corner, or the growingly sympathetic articles about National Socialism in one of the city’s evening papers. No, the signs were visible everywhere for anyone who wanted to see, and he wasn’t one of the blind masses.

Basically he and his family were stuck here. As he looked around, it occurred to him that many of the people gathered in the café would undoubtedly be in the same position. They had nowhere to go. Many were waiting in vain for travel documents and transit visas that would enable onward movement from the northern metropolis in which they found themselves in their escape from worse fates.

He could hear German being spoken behind him, and the exchange was such he couldn’t help following what was said. Two middle-aged gentlemen were in lively discussion about a disastrous voyage across the Atlantic. It was as if the whole room was buzzing with similar tales.

“Apparently certain people were offered entry if they paid five hundred dollars. You can imagine the chaos onboard!”

“How long is the crossing from Hamburg to Cuba? Two weeks, or more? Over nine hundred people tried to disembark. My sister said she received a letter from one of the few who managed it. It might have been one of those who paid. Others tried to throw themselves into the sea in sheer desperation. An entire family went on hunger strike.”

“Naturally it didn’t do any good.”

“Of course not.”

Immanuel had seen some newspaper reports about a passenger ship full of refugees from Germany who had been denied entry permits to Cuba. After futile attempts to stop at a port in Florida, the captain had been obliged to return to Europe with almost a thousand refugees. It had been a veritable hell onboard. Shortage of food and other essentials. Psychological mayhem, mutiny attempts. If his memory served him correctly, they were finally allowed to disembark in Antwerp, hundreds of people without homes to return to. He must have read the story in De Telegraaf. The ship was called the St. Louis, that was the only thing he could remember with certainty.

Immanuel immersed himself in his newspaper but found it hard to concentrate on Albert Oeri’s editorial about the German steel magnate, the greatest of them all, who was in exile in Switzerland. There were too many causes for concern. His wife’s persistent dizzy spells were getting worse and worse. She needed to be seen by a doctor, but would he be able to get her to Sophiahemmet Hospital, as Lagerberg had promised? Another worry was his brother, Gerhard. Right up until the journey to the Latvian resort in the summer he had been a cherished family member, loved by the boys and a true support to Lucia. Immanuel cursed the fact that he had treated his brother’s decision to remain in Poland so lightly. An ingenious young bachelor like him would always find a way to get by, he had said cheerfully. On that warm evening at the beginning of July when they had all set off in a comfortable Russian sleeping car, Gerhard had stood alone on the platform. The boys had hung out of the open window, waving and laughing, as he ran alongside and tried to keep up with the train. Since that time all contact had been lost.

_________________________________

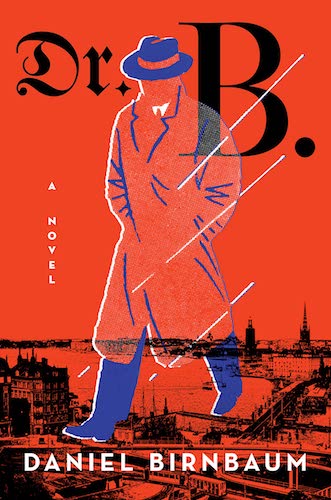

Dr. B. Copyright © 2022 By Daniel Birnbaum. Translation Copyright © 2022 by Deborah Bragan-Turner. Reprinted here with permission of Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.