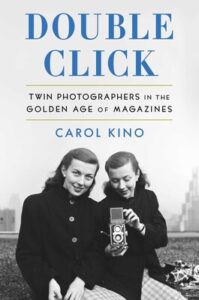

Double Vision: How the McLaughlin Sisters Took the Photography World By Storm

Carol Kino on On Our Enduring Cultural Fascination With Twins

The McLaughlin twins were at the beginning of a several-months-long publicity tour for their book, Twins on Twins, when they appeared on The Dick Cavett Show in March 1981. They had already launched a highly praised show of pictures from the book at a New York gallery and had been widely interviewed, by the New York Times, Good Housekeeping, the Philadelphia Inquirer, and NBC’s Today Show, among others.

They would conclude the tour a few months later with a joint lecture and slide show at Manhattan’s International Center of Photography, located in a mansion on the upper reaches of Fifth Avenue’s Museum Mile, where they were introduced by the organization’s founding director, the photojournalist Cornell Capa.

He had known both twins for years, he said, but now, confronted by them both in the same room, he confessed he had no idea which was which. “I’m completely befuddled,” Capa said. “I can’t make out the difference.” He finally advised the audience that the one in pink was Kathryn, the other was Frances, and that if anyone bought a book that night, they would “get two signatures for the price of one.” Frances tartly chimed in, “But no cut rate on the price.”

At that moment in New York creative circles, twins were regarded as somewhat freakish curiosities.

Yet the high point of the twins’ tour arrived on March 30, 1981, running over into the following night, when they received a full hour of airtime as subjects of a two-part interview hosted by Dick Cavett, the thinking person’s talk show host, whose face, as a New Yorker ad promised, had “launched a thousand quips.” Cavett was known for hosting some of the world’s most revered names in music, politics, and show business, from Groucho Marx and Katharine Hepburn to Bobby Seale, the cofounder of the Black Panthers. Cavett did one two-part interview a week: just before the twins, he devoted it to the African American novelist Toni Morrison, who had recently won the National Book Critics Circle Award for Song of Solomon; just after, to the Italian director Federico Fellini.

Now, as upbeat theme music played, photographs of twins flashed across the screen—twin cheerleaders, twin pianists, twin ballerinas, twin basketball players—until twin Cavetts appeared, a double image produced on the monitor by engineers in the control room. The audience laughed hysterically.

“This is Dick Cavett saying good evening, and don’t touch your TV set, there’s nothing wrong with your picture,” said the host in his flat Midwestern accent. “You’re not having double vision either. You may have deduced by now that you are looking at pictures of twins.”

The camera panned straight to his interview subjects, Frances McLaughlin-Gill and Kathryn McLaughlin Abbe, the twins who had taken the pictures.

Still beautiful at sixty-one, they looked remarkably alike, with the same strongly modeled cheekbones, arched eyebrows, and carefully coiffed shoulder-length blond hairdos—although Frances’s was more of a pageboy, with the ends turned under, and Kathryn’s more of a bob, with the ends flipped up. They were dressed almost identically, too, in pink flowered blouses and tan skirts, differentiated only in that Frances wore a scarf around her neck, while Kathryn wore a vest.

Yet as soon as the conversation began, their dissimilarities became clear. Kathryn smiled and gushed, telling Cavett straightaway, “I like you as twins!” Frances looked politely bored, her eyebrows raised in a slightly haughty fashion, as if echoing the supermodels she had photographed for three decades at Vogue. She only warmed up when Cavett asked which twin jokes they hated most. As Kathryn offered up lots of ideas—“The worst thing you can do is call them ‘twinny’ or make up nicknames” or tell them, “I must be drunk, I’m seeing double!”—Frances tersely said, “Which twin has the Toni?,” a reference to the old home-permanent ad campaign featuring twins, then lapsed back into silence.

Both McLaughlins were among the fairly small group of women to have enjoyed long and successful careers as photographers. Frances had spent thirty years as a photographer for the Condé Nast publishing empire—ten as the only woman among an otherwise all-male top-level staff. Kathryn, after a brief career in fashion, was best known as a photographer of children, with lucrative projects at general-interest magazines such as Good Housekeeping and Parents’.

They were not on the show, however, to discuss their unusual careers. They had been invited to talk about being identical twins, and about their book, for which they had photographed twenty-six pairs of twins and talked to hundreds more about their relationships. Twins such as Samuel and Emmanuel Lussier, who at the age of one hundred were then the world’s oldest identical twins; Fay and Kaye Young, pro basketball players, who had told the McLaughlins how shocked their mother had been by their birth; Peter and Paul Frame, dancers with the New York City Ballet, who spoke of the difficulty of always being seen as the same person, rather than as individuals; and the Rowe and the Richmond twins, who had married one another and lived together in the same house.

“I think if you’re going to go off and marry twins, you set yourself up for quite a bit of attention,” Kathryn said.

“Of course everyone wants to know about the living arrangements,” Frances said to Cavett. “I’d like to know about yours, but you don’t get asked.”

The McLaughlin twins had written their book, Kathryn said, because…nothing had been written that looked at the world from the twins’ perspective.

At that moment in New York creative circles, twins were regarded as somewhat freakish curiosities. The photographer Diane Arbus, whom Frances had photographed several times before Arbus committed suicide in 1971, was now celebrated for her pictures of “social and biological oddities—identical twins, dwarfs, nudists, transvestites, carnival freaks and retarded women,” as Hilton Kramer, the New York Times art critic, had written, on the occasion of her 1972 Museum of Modern Art retrospective; Arbus’s most famous picture depicted a pair of eerie-looking identical girls. The previous year, in Stanley Kubrick’s horror movie The Shining, the central character, played by Jack Nicholson, had experienced a vision of twins as he descended into madness.

But the McLaughlin twins had written their book, Kathryn said, because, while there had been many scientific studies of twins, nothing had been written that looked at the world from the twins’ perspective, on their own terms.

“We’re not scientists—we’re photographers who’ve written a book,” she told Cavett. Their approach, she continued, “is emotional, or really letting the twins speak for themselves.”

“Would you say one is lucky to be a twin?” Cavett asked.

“We think so,” Kathryn said.

Frances disagreed: “Twins are not born by choice.” Most of their subjects had achieved “an equilibrium, where it isn’t completely a burden or completely a pleasure.”

Then the host stepped into more adventurous territory. “Do you know—I blush to even mention this on such a polite program—that there’s a pair of twins who make pornographic films?”

If he thought he’d get a good answer, like the time he’d asked Bette Davis how she’d lost her virginity, he was sadly mistaken.

Both twins looked at him steadily, as though he’d made one of those bad twin jokes they’d heard many times before.

Kathryn politely feigned surprise. “No!”

“Really?” said Frances coolly, as her eyebrows notched somewhat higher. “Men or women?”

Cavett claimed not to recall.

Then Frances stepped in and took control of the interview. “We haven’t talked too much, Dick, about twins in the same career. And as you know, we are both photographers. We decided to become photographers at about the age of eighteen and have never had any other career interest.”

Finally, he asked what they had clearly wanted to discuss all along: How did it begin?

__________________________________

Excerpted from Double Click: Twin Photographers in the Golden Age of Magazines by Carol Kino. Copyright © 2024 by Carol Kino. Reprinted with permission of Scribner, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Carol Kino

Carol Kino’s writing about art, artists, the art world, and contemporary culture has appeared in publications such as The New Yorker, The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, The Atlantic, Slate, Town & Country, and just about every major art magazine. She was formerly a fellow at the Dorothy and Lewis B. Cullman Center at the New York Public Library and the USC Annenberg/Getty Arts Journalism Program. She grew up on the Stanford campus in Northern California and lives in Manhattan. Double Click is her first book.