Doreen St. Félix on June Jordan's Vision of a Black Future

"The poet, critic, and teacher June Jordan was also an architect."

An aerial blueprint of an alternative future disoriented readers of the gentlemen’s magazine Esquire in April 1965. Three rivers—Harlem, Hudson, and East—carve this divergent Harlem as they carve the known Harlem, producing its shape, that maligned almost rectangle. The blueprint’s topography suggests a fiction, or a prophetic vision: Fifteen towers rise above the stubborn city grid, and they are softly curved as if caught spinning on a potter’s wheel, or “abstract, stylized Christmas trees,” to quote the plan’s author, and the towers are connected by a reticulation of thin highways elevated aboveground, and this network originates from an imagined bridge, drawn at the eastern boundary of 125th Street.

The article attributes this Harlem—the Harlem that does not exist—to the architects Richard Buckminster Fuller and Shoji Sadao, collaborators and insurgents designing against the popular credo of public space. (There is the joint signature, scrawled below the East River.) Text, written nearly one year after the murder of James Powell by police lieutenant Thomas Gilligan caused a summer of rage uptown, elaborates on the plan in the rhythm of manifesto. “Harlem is life dying inside a closet,” the writer begins, and then later, “Skyrise for Harlem is a proposal to rescue a quarter million lives by completely transforming their environment.” The vigor of the writing juts out like the towers, puncturing the reader’s received knowledge as to why the Blacks in Harlem were so poor, so riotous, so eternally chained to that undesirable life’s station.

The author writes of life in the housing towers: “No one will move anywhere but up.” Of the reorganized ground near the towers: “Skyrise for Harlem creates cultural centers decked into the sky . . . offering practice studios for musicians, concert halls, theatres, workshops, forums for symposia, dancing pavilions, and athletic fields as well as pathways for strolling under trees.” Of the force oppressive enclosures exert on the human psyche: “There is no evading architecture, no meaningful denial of our position.” Of this Harlem’s spiritual improvement on the known Harlem, “The design will obliterate a valley of shadows.”

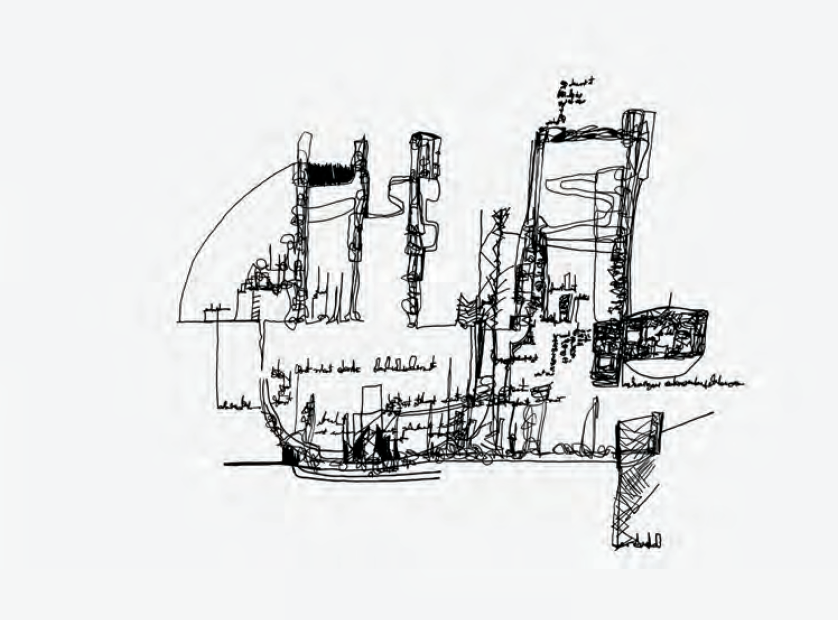

Renee Gladman Prose Architectures 228, 2014 Ink and colored pencil on paper, 9 x 12 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Wave Books

Renee Gladman Prose Architectures 228, 2014 Ink and colored pencil on paper, 9 x 12 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Wave Books

“Skyrise for Harlem” had been the original name of the plan, chosen by its original inventor, the article’s writer, June Meyer. Through marriage she would acquire the surname by which she is known: Jordan. The poet, critic, and teacher June Jordan was also an architect.

Jordan’s sensitivity to environment is observable in the oeuvre she left behind. She was the Black woman writer—an identity that is also a place of exile—always having to establish the philosophical terms of her own world. She rejected how White supremacy razed and rearranged the places where people lived. The June Jordan scholar Cheryl J. Fish suggests the term “architextural” to describe Jordan’s approach to compression, verse, voice.

Esquire published the plan under the headline “Instant Slum Clearance,” forgoing the text submitted by Jordan and Fuller. The magazine also removed Jordan’s name from the blueprint itself. It had been Jordan, then a young mother to her only son, Christopher, a resident of Harlem, a graduate of the architecture program at the American Academy of Rome, who approached the quixotic Fuller about collaborating on a solution to the crises of living in the nation’s invented Black slum. “My title had been ‘Skyrise for Harlem,’” Jordan wrote to Fuller after the publication of the article. “We conceived of this environmental redesign as a form of federal reparations to the ravaged people of Harlem.” It had been Jordan who had written to New York City’s commissioner of housing, figuring out just how deeply the city had shortchanged the Black families living in Harlem. The omission of her name from this radical proposition, and the proximity of her thinking to the thing that the thinking made, is exactly the Black creator’s cyclical condition: dispossessed, and always endeavoring to again own their creation.

June Jordan was the Black woman writer—an identity that is also a place of exile—always having to establish the philosophical terms of her own world.

She had needed the money. The night James Powell was shot, and men and women and children took to the streets to cry out against the arrogance and brutality with which the police patrolled their home, the native New Yorker Jordan went around, frenzied, tending to the wounded. The eco-socialist wanted to release Black residents from the ghetto by obliterating it. (“There is no high school in Harlem,” she writes, “and youth die in traffic deaths more often than in the ‘whole island of Manhattan.’”) Walking through the neighborhood she mused that a sidewalk should not quite end in a corner, which she thought of as a psychological terminus, but would instead swirl into another path. There would be no paucity of green space in her plan. She was influenced by Jane Jacobs, who knew that American cities were machines that had “the capability of providing for everybody, only because, and only when, they are created by everybody.” The plan, Jordan estimated, could be completed in just thirty-six months.

Esquire, fifty years later, in a casual list of “wild predictions” from its archives, lightly derides the plan as “utopian.” Is the structural continuity of the public housing in American cities, which look like prisons, which look like elementary schools, then, reasonable? How we have submitted to the given architecture! Jordan’s cylinders do look uninhabitable because of our complacent picture of what Black urbanites deserve. What if it had been June Jordan who was New York City’s “Master Builder,” rather than Robert Moses? If “Skyrise for Harlem” had materialized?

Renee Gladman Prose Architectures 197, 2013 Ink on paper, 9 x 12 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Wave Books

Renee Gladman Prose Architectures 197, 2013 Ink on paper, 9 x 12 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Wave Books

Drawing extended my being in time; it made things slow. It quieted language. It produced a sense that thinking could and did happen outside of language: I saw it as a line extending from the body, through the hand, as if something were being poured or pulled out of oneself, but here, finally, because it is impossible to achieve this in writing, in time with thought rather than chasing thought through syntax, as something already over, a moment we can now only describe. Drawing was going into time; it was pulling the process of thought apart, and what was most profound was that it left a record behind, a map: the drawing itself. –Renee Gladman

__________________________________

The essay “June Jordan’s Vision of a Black Future” by Doreen St. Félix appears in the book BLACK FUTURES, edited by Kimberly Drew + Jenna Wortham. Copyright © 2020 by Kimberly Drew and Jenna Wortham. Reprinted by permission of One World, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

Doreen St. Félix

Doreen St. Félix is an Haitian-American writer. She is a staff writer for The New Yorker and was formerly editor-at-large for Lenny Letter, a newsletter from Lena Dunham and Jenni Konner. Her writing has appeared in the Times Magazine, New York, Vogue, The Fader, and Pitchfork.