Donal Ryan on Embracing the Evolution of Language While Preserving Its Essence

"There should always be a hint of beauty in its use, even in the mundane and numberless everyday exchanges that fill our existence."

Thirteen years ago, my first novel was published. One of the first reviews it received on Amazon dismissed me as “just another Irish mouther of words.” I was, I have to say, more than a little bit insulted. I am circumspect to the point of obsession about the language I use when I write. Speaking, of course, is an entirely different discipline. Maybe that reviewer had heard me mumble my way through a radio interview or repeat the phrase ah, you know over and over again on a contractually mandated media appearance.

I had to concede, of course, that my debut novel was rendered for the most part from the gloriously blurred, demotic language of my own friends and family, the fractured, Gaelicised syntax of my own people. There certainly are passages that read abstrusely or remain fully opaque to anyone from outside the narrow confines of the lakeside hinterlands of my youth in North Tipperary. Gobshites and goms and Godhelpuses run riot through its pages, bamboozling all but the most assiduous, astute, or native of readers. But I have to admit to a certain obstinacy, a wilfullness, when it comes to this esoteric vernacular; I wanted to represent my own people, the Irish rural working class, as faithfully as was humanly possible on the page.

So in a way, my imprecision was an attempt at precision, at capturing something of the drawled, lilting cadence and weighted laconicism of my countrymen and women. I was trying to describe the indescribable, to sublimate in language—a limited medium—human expression—a limitless medium—limitless because there is an infinity of declensions between death and life, an infinity of ways of being. Language should be soft-edged, pliant and malleable; we should all be able to contort it to our will, to fashion it to our particular tongues and tribes, and there should always be a hint of beauty in its use, even in the mundane and numberless everyday exchanges that fill our existence and give it meaning.

We need to take care of language, we need to remind ourselves of its power, to be mindful of its sacredness, to preserve its integrity.

That’s why I’ve stopped my grumpy middle-aged excoriations of the ‘new accents,’ the strange inflections and tech-savvy lexicons of the younger generations: what matter if a seventeen year old from the west of Ireland who has never been farther than Dublin, and then only the once, speaks with a full American accent and in the opaque (to me, anyway) idioms of the internet native? The only use of language we should rail against is that which seeks to silence others, to separate, or reduce, or force, or inflict suffering or gain unfair advantage, or language that has no time for wonder or for joy.

I don’t think many people actually ask themselves the question “Who should I hate?” Hate seems to make its own way easily, though, it seems to thrive and proliferate in the routes and channels of the online world in particular, where philosophies are parsed to single lines, worth is ascribed or denied according to the contents of a video, or a photo, or any captured moment, where no one can afford to slip up, where everyone is a judge of everyone, and everyone’s opinion is available, all the time. It all seems too much to bear. It seems to me that it takes a few years of supposed adulthood for most human beings to settle into acceptance of the impossibility of certain knowledge, to realize that empathy and dogma cannot co-exist, that moral certitude is a dangerous game, that tendentious language is hard language, barbed and dangerous.

We need to take care of language, we need to remind ourselves of its power, to be mindful of its sacredness, to preserve its integrity. It will change, of course, its stresses and its cadences and rhythms. New words come into being every day, and new idioms, to label all the new things. Technology will continue to create its own lexicon as we progress, and certain words and phrases will lose their places and fall away. This is natural and inevitable. We have to rail, though, against denigration, against malign appropriations of words, against laziness and atrophy, in order that we can be constantly alive to the threat of the closed minds and braying voices of those that are certain, about their morality, their system, their belief, their particular route to salvation.

Truth cannot be codified, or listed as a set of rules; it exists in moments, not in statutes; each individual human truth is ephemeral and chimerical, but it is a truth inviolable and self-evident that all we have on this earth is each other. As the great Limerick poet Michael Hartnett told us:

It happens sometimes, after all the wars

that we meet someone like ourselves—all scars—

and mumble in our minds that hopeful word

‘love’.

__________________________________

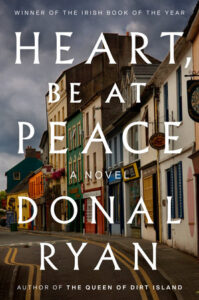

Heart, Be at Peace by Donal Ryan is available from Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Donal Ryan

Donal Ryan is a novelist and short story-writer from Nenagh, Co. Tipperary. He has won several national and international awards for his fiction, and has twice been nominated for the Booker Prize. His work has been adapted for stage and screen and translated into over twenty languages. Donal is a lecturer in Creative Writing at the University of Limerick, where he lives with his wife Anne Marie and their two children. The Queen of Dirt Island, his seventh book, was an instant number one bestseller in Ireland. His novel Heart, Be At Peace is out now.