"Don Quixote," Proto-Feminist Text: How Cervantes' Daughter Shaped His Novel

Martha Bátiz on Telenovelas, Writing Isabel de Saavedra's Story, and Women in the "Quixote"

As a Spanish language native speaker born and raised in Mexico City, I have been familiar with the figure of Miguel de Cervantes my entire life. He is, after all, the author of our most important book, Don Quixote de la Mancha, which was an instant best-seller since its publication in 1605, remains one of the most translated books in the world after the Bible, and is considered the first European modern novel.

Besides, the Spanish language is known as “la lengua Cervantina” (the language of Cervantes). And who hasn’t heard of the lanky knight and his faithful squire, or at least seen their iconic images somewhere?

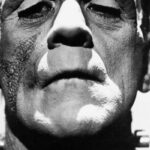

I analyzed various excerpts of the novel in high school, and read the novel multiple times myself. But I knew more about his masterpiece than about the man himself, other than the basic, well-known facts: that he lost the use of his left arm in a famous battle, for which he was nicknamed The one-handed man of Lepanto, and that he was captured by pirates on his way back to Spain and held captive in Algiers for five long years.

It was only as a graduate student, while researching his plays for my doctoral dissertation, that I came across the academic and historic accounts about the women in Cervantes’ family. I learned that Cervantes had a very close relationship with both his sisters, Andrea and Magdalena, though they had an unfavorable reputation.

(They couldn’t have been that bad, however, as it was thanks to their hard work that Cervantes’ ransom was paid and he was freed from captivity.) He also had a good relationship with his niece, Constanza.

The biggest surprise was that Cervantes had a fathered an illegitimate daughter, Isabel.

The biggest surprise was that Cervantes had a fathered an illegitimate daughter, Isabel. Literary critics and scholars often referred to her as “an ingrate,” “a brat,” and “a bitter woman”—in short, as a source of great anguish for him.

Growing up, Isabel lived with her mother and the man she believed to be her father, who was a taverner in Madrid. He died when she was young and her mother took charge of the family business on her own (a feat in itself for a woman in those days) until the plague took her life. Isabel was fourteen. Shortly after that, she learned that her real father was Miguel de Cervantes.

She moved in with Andrea, Magdalena, and Constanza, posing as their maid to preserve the family’s honor in general—and Cervantes’ wife’s honor in particular. His wife—Catalina de Salazar y Palacios—was a very pious woman who had not been able to give Cervantes any children. She was also oblivious to Isabel’s existence.

Is it a surprise, then, that the female characters that inhabit Cervantes’ literary work were beautiful and virtuous women who had been wronged by society, yet found a way to stand strong? Others, such as the fictional shepherdess Marcela in Don Quixote, decided to lead a life of solitude and freedom away from both men and the confines of the convent.

Through his female characters, Cervantes showed compassion towards the plight of women and the many restrictions imposed on them by society at the time. Could this approach be his written response to the female suffering he witnessed all around him, and particularly at home?

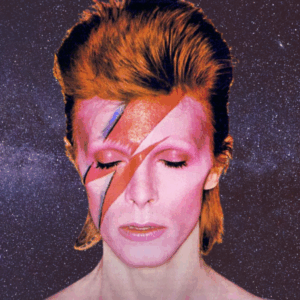

The story reminded me of the hundreds of telenovelas I grew up watching (and sometimes acting in) in Mexico City, and their typical plot: poor, destitute girl is hired as a family’s maid only to fall in love with the rich boy she serves, or to discover that she is the heir to the family’s fortune (and all hell breaks loose). Educated by her aunts, Isabel proved to be smarter and even more fiercely independent than them, much to her father’s chagrin.

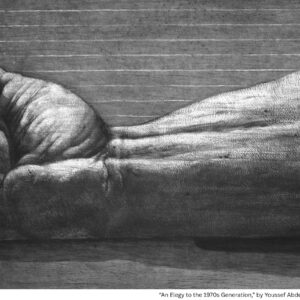

But where my male academic peers saw betrayal and ingratitude, I saw grief and bravery. What Isabel was able to accomplish in her lifetime, and the choices she had to make to get there, were nothing short of remarkable. She learned the rules of the game and positioned herself as an unlikely, yet uncontested winner.

It is easy to imagine what it must have been like in the early seventeenth century in Spain for someone like Isabel, when the Inquisition was all the rage and being an illegitimate child was a stigma that made it almost impossible for anyone to thrive. It was not difficult for me to conclude that she had been misjudged. How come no one has righted this wrong, I asked myself. Isabel’s story needs to be told from her perspective! She deserves justice!

I discovered that a few attempts had been made to fictionalize her life, but I always sensed an accusatory tone between the lines (or, sometimes, quite openly). Even today, society still points its finger at successful, independent women and calls them callous.

But I hesitated. As a Mexican writer living in Canada, what right did I have to tell this story? After some thought, I remembered the years I spent working as an actress in various telenovelas in Mexico City. How much at home I felt in their sets; how I enjoyed watching them at home.

What is magical about telenovelas, I think, and has contributed to their success, is the fact that they are made to be understood and enjoyed by anyone. I remember how empty the normally busy Mexico City streets became on the evening the final episode of a few of those culebrones aired. Everyone was glued to their TV screens, and people talked about the show’s ending for days on end.

Why not, then, try to share with English-speaking readers what I had learned about Miguel de Cervantes and the women in his family by striving to recreate this same kind of experience? Why not portray their dramatic stories with care and respect, focusing on these courageous yet disparaged women, while also shedding well-deserved light on a great writer that should be widely (re)read again?

What is magical about telenovelas, I think, and has contributed to their success, is the fact that they are made to be understood and enjoyed by anyone.

I decided that my desire to defend Isabel, and the love I feel for Cervantes’ work, and for Spain as a nation, were reasons enough for me to take the plunge. I crossed myself, and sat down to write. This is how my novel A Daughter’s Place was born.

______________________________

A Daughter’s Place by Martha Bátiz is available via House of Anansi.

Martha Bátiz

Martha Bátiz an award-winning writer, translator, and professor of creative writing and Spanish language and literature. She is the author of five books, including the short story collections No Stars in the Sky and Plaza Requiem (winner of an International Latino Book Award), as well as the novella Boca de lobo / Damiana's Reprieve (winner of the Casa de Teatro Prize). Born and raised in Mexico City, she now lives in Toronto. A Daughter’s Place is her first novel.