Does the Supreme Court Really Just Run on Vibes Now?

Leah Litman Explains the Legal Theories Weaponized by Conservative Justices Against the Administrative State

As Patrick Bateman reflects on being a serial killer hiding among lawyers, he says, “There is an idea of Patrick Bateman; some kind of abstraction. But there is no real me. I simply am not there.” Under all of the Republican justices’ hand-waving about legal theories and interpretation, there is similarly no “there” there—there’s no attempt to say what government should look like or why it should be that way. It’s a vacuous, nihilistic black hole, and the “law” that accompanies it isn’t much better.

Over time, Republican judges and justices have pushed a few different jurisprudential theories, which again are just theories about how to interpret the law. When courts say they are using a “jurisprudential theory” or “interpretive methodology,” that suggests they are doing something other than politics. But just as jurisprudential theories about the Constitution can overlap with political philosophies, so, too, can jurisprudential theories about statutes.

Legal decision-making inevitably involves consulting background principles about the nature of government, and these legal-ish sources overlap with political philosophy. Sometimes jurisprudential theories will draw upon legal principles that are both legal principles and political philosophies—such as the idea of limited government. Other times, the connections will be more subtle. Take two jurisprudential theories that picked up steam during the Reagan years, the so-called Chevron doctrine and textualism. Both theories concern how to interpret statutes—textualism is about statutes in general, and Chevron was about the statutes concerning administrative agencies.

Over time, Republican judges and justices have pushed a few different jurisprudential theories, which again are just theories about how to interpret the law.

The Chevron doctrine told courts to defer to administrative agencies’ reasonable interpretations of statutes when they are unclear. The Chevron case concerned the Clean Air Act, which requires certain states to issue permits for new or modified “major stationary sources” of air pollution. The question in Chevron was what constitutes a “stationary source.” Does that mean the individual pollution-emitting devices within a power plant, or the whole entire power plant? If “stationary source” meant the whole power plant, then existing power plants could construct new pollution-emitting devices without obtaining a permit.

Naturally, Reagan’s EPA, led by Anne Gorsuch Burford, selected that interpretation, which imposed fewer constraints on polluters. In Chevron, the Supreme Court said that the EPA’s interpretation of the statute was fine, not because the justices thought it was correct, but because they concluded the statute wasn’t totally clear. Therefore, the Court reasoned, the expert agency that was more accountable to the people should resolve the issue rather than the federal courts. In the Chevron case, the Chevron doctrine inured to the benefit of Republicans’ preference for less regulation, but the doctrine could theoretically cut both ways: both Democratic- and Republican-led agencies should receive deference when they interpret ambiguous statutes.

Something similar could be said of another jurisprudential theory embraced by Republican appointees in the Reagan years, textualism. Textualism refers to the idea that federal statutes should be interpreted according to their text, i.e., their words. Textualism is supposed to prevent courts from focusing on the purpose of a statute, meaning what Congress sought to accomplish—the statute’s goals. In theory, textualism should not favor one political project over another, but textualism became an insurgent theory in the midst of Republicans’ booming hostility to industry regulation, which has shaped how textualism is understood and practiced to this day.

It’s kind of like originalism in that respect: originalism is supposed to be a neutral methodology that directs courts to focus on the ideas held by the people who ratified the Constitution. But that is not especially neutral because of the values and worldviews of our forebears, and because originalism took shape as Republicans sought to advance their views on certain social policies through the courts, which has shaped how originalism works to this day.

Some conservative scholars and judges have linked textualism to a theory that is hostile to the very existence of the administrative state—nondelegation. Bear with me for a second because this is going to sound technical, but it’s important. It could lead to the murder of the administrative state. Nondelegation is an idea, not a doctrine, because it’s not actually the law. Yet. (It’s more of a vibe.) The nondelegation vibe says that Congress generally cannot delegate certain authority (the authority to tell private parties what to do) to other entities, including administrative agencies. Some people (lawyers) have cobbled together a little cherry-picked history, a few selective quotations, and a side of political philosophy (of limited government) to insist that nondelegation is, or should be, the law.

Taken seriously, nondelegation would mean there would be no regulation, period, at least outside of some pretty narrow exceptions. It would mean that most everything would have to be done via statutes passed by Congress, the body of people who can’t even describe how the internet works. Yikes. Nondelegation is so extreme the Supreme Court has never really attempted to use it to prevent Congress from delegating authority to administrative agencies except in 1935, when the Court was insisting the federal government couldn’t address the Great Depression.

That year, the Court struck down two New Deal programs by relying, in part, on non-delegation principles. In one case, the Court declared that Congress had exceeded “limitations of the authority to delegate.” That was the last time the Court ever attempted to enforce a nondelegation constraint against Congress. Since then, the Court has upheld delegation after delegation, though a growing number of Republican justices would apparently like to take us back to the good old days of 1935 (which, to be clear, was during the Great Depression).

Textualism supposedly furthers nondelegation principles because it ensures that private citizens and corporations have to do only what is required of them by Congress. In the words of Judge Frank Easterbrook, one of Ronald Reagan’s most well-known and influential judicial nominees outside of the Supreme Court, textualism is about “Congress. Let it make the rules.” That idea echoes a sentiment behind the push to revive nondelegation, a desire to have Congress do everything by statute (which would probably mean a lot less industry regulation). One influential scholar (and later dean of Harvard Law School), John Manning, wrote an article in 1997 entitled “Textualism as a Nondelegation Doctrine.” The article has been cited in judicial decisions, including a 2022 case authored by one of Donald Trump’s judicial nominees.

Justices and judges could adhere to both textualism and Chevron since textualism is about statutes in general and Chevron was about a subset of statutes—those concerning administrative agencies. Having multiple theories and exceptions or addenda to those theories isn’t a bad thing; it’s inevitable in a complex world where a one-size-fits-all approach to judging won’t fly. But deciding when one theory applies rather than another, or developing different caveats or addenda to those theories, is part of why the ordinary business of law involves some discretion. That there are multiple jurisprudential theories, as well as limits to any jurisprudential theory, is one reason why law leaves some room for vibes.

Simply applying a single jurisprudential theory leaves some room for vibes. This is true for originalism, a method about how to interpret the Constitution. It is also true for methods of interpreting statutes, the bread and butter of what courts do. Jurisprudential theories such as textualism offer courts a bunch of fancy-sounding rules that seemingly add to the mystery of the judicial enterprise while in reality adding to judges’ discretion. Take the canons of construction, a set of rules about how to do textualism. Noscitur a sociis and ejusdem generis sound complicated and mysterious, but despite the fancy Latin terminology, they just refer to the idea that the meaning of words is informed by the words surrounding them. Imagine that someone says, “Get the pot.” Does the person mean the pot as in the pan, or the pot as in the marijuana? If the person had said, “Get the pot and the pan,” it’s probably the former; if the person had said, “Get the pot and the edible,” it’s probably the latter.

The Republican justices used this idea to nuke the CDC’s moratorium on evictions during the COVID-19 pandemic, turning the canons of construction into literal canons against the administrative state. The first sentence of a federal law gave the CDC authority to make “regulations” the agency determined were “necessary to prevent the introduction, transmission, or spread of communicable diseases.” The agency decided that an eviction moratorium was necessary to prevent the spread of COVID-19. So the Republican justices declared that “the second sentence” of the law “informs the grant of authority” in the first—and limits the agency’s authority. The second sentence said the CDC “may provide for such inspection, fumigation, disinfection, sanitation, pest extermination, destruction of animals or articles… and other measures, as in his judgment may be necessary”; that list of examples, the Court insisted, restricted the CDC to adopting measures for “identifying, isolating, and destroying the disease itself,” a phrase that is nowhere in the statute.

Maybe that’s right; maybe that’s wrong—sometimes accompanying sentences will limit nearby sentences, but sometimes they will not. The point is the Court made a choice about whether to read the list of possible regulations as illustrative additions to the general grant of authority or as a constraint on it. And what a surprise—the Republican justices made the choice that allowed the agency to adopt fewer regulations.

Some of their discretion arises because judges will decide how a theory applies to different kinds of facts. In applying both textualism and Chevron, the Republican-controlled Court began to consider the “significance” of agencies’ rules or regulations. How the Court defined significance wasn’t clear, but the Court suggested that, if a rule or regulation was economically significant in that it would cost a lot of money (to industry), courts might consider that as some evidence about what a statute meant—alongside the statute’s text, structure, design, and whatnot. That’s not especially textualist, but it’s an example of how theories such as textualism have exceptions and can be stretched and applied in ways that give discretion to judges.

While the Court embraced theories such as textualism and Chevron, the justices balked at more outlandish efforts to constrain administrative agencies. Such as nondelegation—the idea that most regulations are unconstitutional, and most everything has to be done by statute. Even the Republican appointees at the time couldn’t stomach that one. In 2001, the Supreme Court rejected an effort to make nondelegation the law of the land in a challenge to the Clean Air Act (CAA). The CAA authorized the EPA to make regulations setting national air quality standards for air pollutants. An industry group, together with states including West Virginia, challenged the law as unconstitutional. The challenge was so extreme, Justice Antonin Scalia rejected it. His opinion explained why the Court frequently allows Congress to delegate authority to agencies in extremely general terms such as allowing officials to regulate where “necessary to the public safety” or in the “public interest.”

Justice Thomas wrote separately, noting that “none of the parties to these cases” have “asked us to reconsider our precedents on cessions of legislative power. On a future day, however, I would be willing to address the question whether our delegation jurisprudence has strayed too far from our Founders’ understanding of separation of powers.” And he wasn’t the only federal judge flirting with the prospect of murdering the administrative state.

“Executive bureaucracies… concentrate federal power in a way that seems more than a little difficult to square with the Constitution of the framers’ design. Maybe the time has come to face the behemoth,” Neil Gorsuch wrote in August 2016.

In 2016, Republicans pulled off the establishing shots of their heist of the Supreme Court after Justice Antonin Scalia unexpectedly passed away in early February. Within a week, then Republican Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell declared that the Senate would not consider anyone nominated by Democratic then-president Barack Obama. McConnell said this in February even though Election Day was in November. When Obama eventually nominated Judge Merrick Garland, one of the most moderate and respected appellate judges in the country, Republicans stood firm. Why?

According to the Senate majority whip, Republican John Cornyn, “The next justice could change the ideological makeup of the Court for a generation.” It’s tempting to wonder what Republicans would have done if the shoe had been on the other foot and they were in the minority of a Democratic-controlled Senate that refused to confirm any nominee from a Republican president. Except it’s borderline impossible to imagine Democrats playing that kind of hardball.

Republican politicians have a pretty good idea how judges will rule in a host of important cases even when judges are not nakedly partisan.

In November 2016, Donald Trump was elected president, and for the Supreme Court he selected Neil Gorsuch, the son of Anne Gorsuch Burford, Reagan’s deregulatory EPA administrator. Leonard Leo, the vice president of the Federalist Society, who was advising the administration on judicial nominations, said that “the next step in the national debate about the proper role of the courts” is the “administrative state,” which he described as “a huge, glaring issue.”

Republican politicians have a pretty good idea how judges will rule in a host of important cases even when judges are not nakedly partisan and do not say stuff along the lines of “I’m a Republican opposed to regulation.” Judges provide other clues that may be wrapped in legal trappings rather than phrased as policy views. When Trump selected Gorsuch for the Supreme Court, for example, Gorsuch had already established himself as an archenemy of the administrative state. In an August 2016 decision ranting about the executive bureaucracy, for example, then-judge Gorsuch took the unusual step of writing both a majority opinion and a concurring opinion, which is odd since a concurring opinion is usually for a judge who doesn’t think the majority opinion captures their views.

Why would a judge who wrote the majority opinion also write a concurrence? Neil Gorsuch had a point he really wanted to make—he really had it out for the administrative state. He began the concurrence by saying, “There’s an elephant in the room with us today….The fact is Chevron permit[s] executive bureaucracies to concentrate federal power in a way that seems more that a little difficult to square with the Constitution of the framer’s design. Maybe the time has come to face the behemoth.” Gorsuch added that he also had some doubts about the cases allowing Congress to delegate authority to administrative agencies. He wrote, “Some thoughtful judges and scholars have questioned whether standards like these serve as much as a protection against the delegation of legislative authority as a license for it.”

In 2017, Trump White House adviser Steve Bannon said that many of the administration’s nominees “were selected for a reason, and that is deconstruction.” Following Reagan’s playbook, the Trump administration picked executive branch nominees who would try to destroy the administrative state from within. After promising to “get rid” of the EPA, Donald Trump selected Scott Pruitt as EPA administrator. Pruitt had previously served as attorney general of Oklahoma, where he had sued the EPA many times, including over pollution standards. As EPA administrator, Pruitt mused that carbon dioxide and “human activity” were not, in fact, a “primary contributor to the global warming.”

The Trump administration took a similar approach to selecting judges. Trump’s White House counsel pretty much came out and said this: “What you’re seeing is the president nominating a number of people who have some experience, if not expertise, in dealing with the government, particularly the regulatory apparatus. There is a coherent plan here, where the judicial selection and the deregulatory effort are really the flip side of the same coin.”

Most Democrats refused to go along with McConnell’s Supreme Court blockade and voted against Gorsuch’s confirmation in 2017. That led Republican senator Lindsey Graham to declare in agony, “I don’t know what to do other than to change the rules.” So that’s what they did; they changed the rules, abolished the sixty-vote filibuster requirement for Supreme Court nominees, and installed Gorsuch on the Court.

A year later, in 2018, a nondelegation challenge reached the Supreme Court, which had only eight justices at the time because Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s confirmation was in limbo after several people accused him of sexual assault. This particular case sought to make nondelegation into the law, and it involved (of all things) the Sex Offender Registration and Notification Act, which gave the attorney general the authority to determine when to subject people who were convicted before the act’s effective date to the registration requirement. The then four Democratic appointees declined to adopt nondelegation as the law of the land, and Justice Alito wrote separately to say he would not do so in this case, but would consider doing so later, when the Court was fully staffed: “If a majority of this Court were willing to reconsider the approach we have taken for the past 84 years, I would support that effort.” Justice Gorsuch dissented, writing that he “would not wait.” He preferred to go full-on nondelegation crazy now, and Justice Thomas and Chief Justice Roberts would have gone over the ledge with him.

When moderate justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg passed away less than two months before the next presidential election, the Republican Senate’s opposition to filling a Supreme Court vacancy during an election year—and, indeed, while an election was already underway—vanished. As Republican senator Richard Shelby explained, “We’re in control of the presidency, we’re in control of the Senate, why not?…There’s a political fight in here, too.” Just one week and one day before Election Day 2020, Republicans confirmed Justice Amy Coney Barrett to the Supreme Court. Only Republican Senators voted to confirm her, and by that point, more than 60 million votes had been cast in the election that Donald Trump lost.

__________________________________

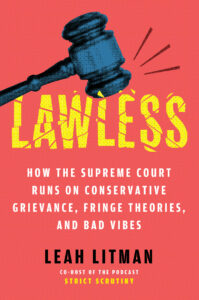

Excerpted from Lawless: How the Supreme Court Runs on Conservative Grievance, Fringe Theories, and Bad Vibes by Leah Litman. Copyright © 2025. Published by Atria/One Signal Publishers, an imprint of Simon & Schuster.

Leah Litman

Leah Litman is a professor of law at the University of Michigan and a former Supreme Court clerk. In addition to cohosting Strict Scrutiny, she writes frequently about the Court for media outlets including The Washington Post, Slate, and The Atlantic, among others, and has appeared as a commentator on NPR and MSNBC, in addition to other venues. She has received the Ruth Bader Ginsburg award for her “scholarly excellence” from the American Constitution Society and published in top law reviews. Follow her on X @LeahLitman and Instagram @ProfLeahLitman.