Do We Still Know Our Own Faces in This Tech-Dominated Society?

Jessica Helfand on the Clarity and Secrecy of Human Faces

A baby’s face is the face of promise, but it is also the face of provenance. To look at the face of an infant is to easily look beyond the staggering reality of the present—the individuation of a fledgling soul, the incomprehensibility of its biological uniqueness—and see a blank slate. Hopeful projections are human truths: we project onto others what we see in our own likenesses. The face is nothing if not a creature of habit.

Perception may be one of the great core capacities of the human intellect, but in an age of robotic simulation, visual manipulation, and a seemingly unstoppable torrent of fake news, it’s also an imperiled enterprise. How do we even begin to perceive difference, discerning the artificial from the authentic, the face from the facsimile?

The face has always been a hieroglyph, at once an instrument of lucidity (we all have one) and an enigmatic canvas (we’re all different). Its backstory includes misguided methodologies, implausible fictions, and epic tales of narcissism. (Its future is no less colorful.) Writing nearly a century ago, the Hungarian film theorist Béla Balázs described cinema as a machine that would turn our attention back to a visual culture and give us new faces.

Today, that once-new cinematic machine has expanded to include an entire spectrum of seductive technologies—mobile, social, virtual, wearable, and endlessly visual—that challenge how we see both ourselves and each other. What happened to our old faces, and how do we get them back?

Who has the right to take a photo of someone else’s face, and why? What are the social conventions framing that right, the societal expectations motivating us to do so, the politics and ethics guiding the publication and dissemination, over time, of anyone’s likeness? Who decides who gets to share? The question of who owns our data all too often gets in the way of a more immediate concern: who owns our faces? Arguably the feature with which we are most highly individuated (your DNA sequence, though unique, remains hidden from public view), the face is social currency, a mashup of history, heredity, culture, posture—and pure, dumb luck. (Or, for that matter, no luck.)

How we present to the world, who we present to the world, the way we navigate bias, calibrate judgment, and traffic in the persistent uncertainty of all that is profoundly human—these are the means by which we visually (and viscerally) scrutinize ourselves and each other. All reflections boomerang back to us. The mirror, it turns out, does not lie.

Except that it does lie—it must. It also fragments and conceals, reframes, masks, manipulates, cajoles, and labels us all. We are, at any given moment, prey to a series of ineffable (if ultimately rhetorical) classification schemes, all of us actors wearing multiple hats, playing plural roles, awash in a culture of pantomime. We smile for the camera, until we don’t. (Consider passport pictures.) We hide from the camera, until we can’t. (Consider candid pictures.) We turn to the camera for proof, at once a diagnostic gesture and a deceiving one: the mirror may not lie, but a picture certainly can.

The photo itself can be lit, cropped, doctored, distorted, airbrushed, redacted, or refashioned to amplify (or nullify) a particular trait. Consider social platforms like Facebook and Snapchat, Pinterest and Instagram—and all that they portend. (And then consider plastic surgery. And eugenics.) Facial recognition, once a sentient behavior, is now a technological conceit. Who’s behind the camera—or in it?

Where there is software there is hardware. And here, in the so-called age of personal agency, the ability to turn the camera on yourself represents a stunning reversal of authority. It bears saying that today’s smartphone contains a lens pivot so graceful that your subject and object can easily share a single, fluid orbit. You may think you’re the one behind the camera, but are you, really?

As the pendulum of digital sophistication swings ever outward, that orbit gradually expands to include a host of technologically enabled deputies to do the work for you, from vigilant security cameras protecting your property to voice-activated baby monitors soothing your children. How much is too much? How fast is too fast? Now that facial recognition can unlock your phone for you—who’s behind the camera, now?

Photographic portraiture requires, perhaps by its very nature, a certain basic interpersonal complicity, but this has not always been the case: indeed, an individual can be staged to submit to all manner of posturing. The French 19th-century neurologist Duchenne de Boulogne used electrical probes on his subjects’ faces to elicit particular expressions that he subsequently captured on camera. (That these subjects were also day laborers illuminates, in no small way, a social manipulation that was at once deplorable and seemingly disregarded.)

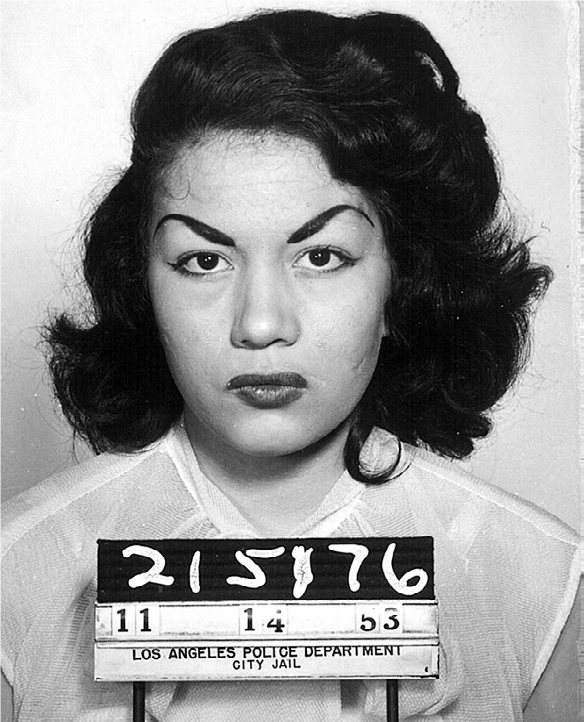

Later in the same century and the same country, Parisian forensic documentarian Alphonse Bertillon would measure the faces and features of criminals in an effort to introduce a systematic—and to his mind, scientific—overhaul of what was, at the time, a criminal justice system in disarray. Here, too, the question of who was measured, where their photos resided, and how a given suspect’s data might be deployed in the service of bureaucratic superiority raises concerns about how we codify the faces of others. (Or that we do so at all.)

The micro-maneuvers here—the powerful against the powerless, privacy at the hands of piracy—shed light on rather an astonishing kind of hubris. In these experiments, and at the hands of these men (self-proclaimed experts, all) the camera itself functioned rather unilaterally as an instrument of unbridled privilege.

Bertillon’s anthropometric calculus combined photos and related metrics to identify criminals, and by conjecture, to anticipate nefarious activity, a practice that ignited a renewed interest in recidivism. (The introduction of frontal and side-view photographic diptychs were key to this practice: Bertillon also famously pioneered the mug shot.) His Italian colleague, Cesare Lombroso, a physician and a criminologist, and a fervent disciple of social Darwinism, used physiognomy—or physical character assessment—to reinforce the far more pernicious theory of atavism: the assumption that a “born” criminal could be identified by his or her physical characteristics. To the degree that pictures speak louder than words, faces, in the context of these morally troubling experiments, spoke volumes.

Yet if criminology proved a fertile environment for classifying the faces of the accused, it was by no means the only discipline in which portraiture proved indispensable. Indeed, the invention—and subsequent popularization—of the camera itself made such efforts eminently achievable. Curiously, photographic experiments were common practice throughout the asylums of turn-of-the-century Europe, most regrettably among physicians for whom willful diagnostic assertions frequently trumped basic human dignity.

From Paris, where the French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot used photography to record his patients’ “hysteria,” to Surrey, where the British psychiatrist Hugh Welch Diamond photographed his patients’ faces to confirm certain kinds of mental illness, the rights of the poor, the infirm, the racially or religiously or otherwise socially marginalized were, particularly given the context of their often involuntary captivity, sorely neglected in the service of science.

Captivity itself seems an unusually apt metaphor for experiments like these, in which patients were typically propped up in their beds, not unlike trained animals at a zoo. The idea of the patient as a kind of performative prisoner recalls the model of the police line-up (in Britain, these are somewhat lyrically referred to as “identity parades”) and loosely resembles the manner in which our children are asked to congregate annually for class photos.

Again, the question of who’s behind the camera looms, begging the question: when did the class picture become a standard rite of back-to-school passage—and when did parents first willingly submit to the notion that this purportedly objective yearly snapshot would become part of the public record? The dilemma of whether or not to post photos of a toddler on Facebook may trigger concerns about the rights of minors, but the annual school photo normalized this behavior long before our current preoccupation with the ethics of online posting.

Those seemingly innocent class line-ups go one step further by laying bare the faces of sameness and difference. (And otherness: circus freak shows spring to mind.) Often relegated to the stuff of nostalgia—we can all marvel at the outmoded clothing and bad haircuts and mortifying orthodontia that we’d much prefer to forget—we are, at the same time, being catapulted into a game of unconscious comparison, routinely measuring ourselves against type, and, worse, against each other.

Who was behind the camera, indeed: and who was behind the decision to photograph our children year after year after year? The idea that pictures of our children would inevitably come to be shared by our children might seem a foregone conclusion, but weaponizing those photos as agents of bullying—an unfortunate, if inevitable consequence of all that sharing—stems from a kind of social one-upmanship that has a complicated history all its own. Isn’t “keeping up with the Joneses” a form of human measurement? Maybe the line-up was always a freak show.

__________________________________

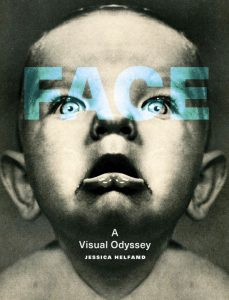

Excerpted from Face: A Visual Odyssey by Jessica Helfand. Reprinted with permission from The MIT Press. Copyright 2020.