Disgust: On the Uses and Abuses of the Most Difficult Emotion

Stephanie Grant Unpacks the Categories of Our Revulsion

Although not widely reported, it’s known that, on January 6th, some of the insurrectionists who assaulted the Capitol Building defecated in the Halls of Congress and tracked their feces wherever they went. Analysts have described this behavior as one of aggressive appropriation: This is my house; I can do what I please here.

Likely, the reader has seen many photographs from that day which confirm this view: Trumpers reclining, feet up, in Nancy Pelosi’s office, stealing the Speaker’s lectern, rifling through members’ papers at their desks. It does not require unusual insight to understand that pooping in the Halls of Congress is a gesture that expresses contempt for the people who work there. But, as a writer who has been thinking about disgust for the last several years—since the 2016 presidential election, in fact—I can’t help but see the rioters’ defecation through the lens of this singular emotion.

According to social scientists, disgust’s initial (evolutionary) function was to protect the body from contamination. Before the advent of germ theory, disgust kept us away from bad smells, rotting food, oozing wounds, and decaying corpses. Contemporary disgust, these same researchers suggest, no longer safeguards the body, but instead protects the soul. These days, we, the body politic, fear a different kind of contamination.

The Radical Right has long made deft use of this distressing emotion to organize its constituents, exploiting in special measure the sense that the disgusting thing, no matter how incidental the encounter, has already corrupted us. Since well before the AIDS crisis, the Right has mobilized the public’s moral, sexual and pathogenic disgust against queer folks. Indeed, when I was growing up, in the 1970s, a single same-sex encounter was understood to turn you into a homosexual. Researchers (including anthropologists) call this belief—once in contact, always in contact—sympathetic magic. In 1992, the year I turned 30, the Right’s infamous video, The Gay Agenda, painted us as dangerous contaminants, whose corrupting influence was a threat to the American family and their (supposedly homogenous) values. Notably, the video asserted that gay men “ingested feces” with regularity.

To better understand how disgust protects our souls, we need to become aware of its function as a stabilizer of social norms: people are disgusted when they discover an object or person is in the wrong place, the proverbial hair in the soup. Or, to put it another way, one that is perhaps more apropos to the assault on the Capitol: dirt isn’t dirty when it’s outside. According to this logic, disgust erupts when the categories and oppositions that structure our daily experience fail to stay distinct: clean vs. filthy; inside vs. outside; us vs. them.

The in-real-time responses of left-leaning news analysts to Trump’s rioters were brimming with precisely this type of contempt. What were these people doing in the halls of Congress? Many of the TV journalists who attempted to narrate what was unfolding deployed the rhetoric of disgust well before they (and we) knew the extent of the violence committed by the rioters or understood their murderous intent. In other words, at the precise moment when the assault seemed more improbable spectacle than deadly insurrection, we were already disgusted by the people staging it. I’m certain the rioters knew they were being viewed this way—why else take so many selfies if not to document their own incongruity?

Expressing disgust for other human beings is the first step in dehumanizing them.

I make note of their reception by the media not to offer sympathy to the rioters, but rather to see more clearly what they were up to. Disgust is a problematic feeling to declaim in a democracy because doing so explicitly expresses one’s superiority over the person one is disgusted by. Activists on the Left have long known this and, as a result, have chosen to articulate their vision with the language of rights, human and civil, instead of the language of moral approbation so appealing to the Right. Trump’s signature political intervention may well be his ability to provoke the Left’s disgust, a tactic gleefully embraced by his supporters on January 6th.

As anyone who has spent time with a small child knows, behavior is a form of communication. If, by defecating in the halls of the Capitol Building, the rioters were expressing their contempt for Congress, they were simultaneously inviting those of us watching to revel in our disgust for them. This strategy—to goad the opposition into abandoning, not civility, but its own values—is a favorite of autocrats and bullies, including, of course, the ex-president himself. Expressing disgust for other human beings is the first step in dehumanizing them, a gesture necessary to waging war, including especially civil wars—my neighbor is no longer my neighbor—and to building fascist states.

If disgust’s hierarchizing function is problematic in a democracy, the feeling is no less disturbing in our intimate relations. When, in my twenties, I came out to my Irish Catholic parents as a lesbian, they responded by articulating their disgust in different ways: my mother applied what she believed about the category lesbian—lonely, perverse, a danger to children—to the category Stephanie, whereas I had been hoping she would do the reverse, allowing her experience of me to revise her understanding of lesbians.

My father, verbally more reticent than my mother, found his body stepping in to speak: he suffered a bout of diarrhea. This is difficult to acknowledge, let alone commit to paper, as the appearance of feces might provoke the reader’s own disgust, who might then turn away from this particular manifestation of turning away. Social scientists have deemed feces “the universal disgust object” because its intimate foulness reminds us of our inevitable decay, our animal vulnerability. These same researchers are not in agreement about what feeling is the precise opposite of disgust. Some say love, others trust.

Although my father was a life-long Democrat, it’s not difficult to trace a line between his diarrhea and Trump’s defecating insurrectionists. In both instances, those expressing their disgust were protesting a reality they could not, would not accept. Now, more than 30 years after coming out to my parents, and 29 years after The Gay Agenda was distributed to every member of Congress (in the self-same building where Trump insurrectionists would eventually, contemptuously defecate), now I understand my parents’ disgust as an attempt to forestall their own approaching mortality, a refusal to accept all they’d sacrificed only to have their daughter repudiate those lives and the values that informed them.

Except that, by coming out, I was enacting their values—honesty, integrity, self-determination—not repudiating them. Heartbreakingly—and I assure you, it was a heartbreak for us all—they could not see that.

___________________________________

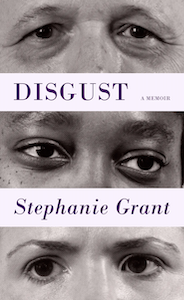

Stephanie Grant’s Disgust: A Memoir, will be published by Scuppernong Editions in November 2021.

Stephanie Grant

Stephanie Grant is the author of two novels, The Passion of Alice and Map of Ireland. Her non-fiction has appeared in Lincoln Center Theater Review and on the New Yorker website. Her current project, Home Equity, is about marriage and the 2008 housing crisis. She teaches fiction in the MFA Program at American University.