Discovering Ralph Waldo Emerson in the Golden Age of Sneakers

From Run DMC to Spike Lee to "Self-Reliance"

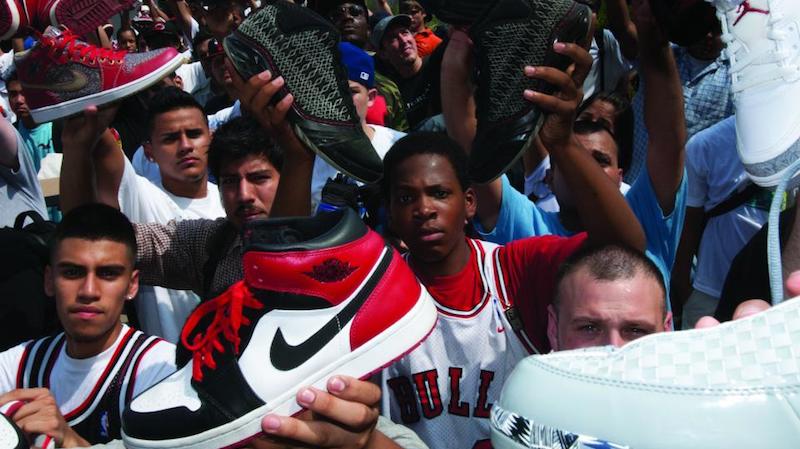

I grew up during the dawn of the sneaker era, the genesis of which was not only concurrent with the golden age of hip-hop but constitutive of it. In the same poor neighborhoods that spawned rap music, sneakers were a kind of vocabulary for abundance, a way to undercut poverty while underscoring style and toughness. It wasn’t long before the first major hip-hop endorsement deal was signed: in 1986 Adidas partnered with Run DMC. The duo’s laceless take on Adidas’s classic three stripe shell toe was instantly iconic. Demand for these cash crop logos, the greatest of which was Nike’s Jumpman, eventually inspired gunshots and sweatshops. Thirty years later the same sneakers for which teens were robbed now compel collectors to loop city blocks for the chance to buy them.

I was no sneakerhead but like every kid in my neighborhood, I thought about sneakers. They started showing up in great rap songs from the very beginning. On the first rap song I ever heard, Slick Rick’s now over-sampled 1985 hit “La-Di-Da-Di” had me wondering what Ballys were years before Tupac claimed Chucks over Ballys in “California Love.” In “I Got to Have it,” Ed O.G. instructed fake friends to don their Adidas before stepping off. In “Word from Our Sponsor,” KRS-One wore only Nikes. Throughout The Low End Theory, Phife rocked modest New Balances.

In 1988 Reebok was looking to answer Nike’s hugely popular “It’s Gotta Be the Shoes!” campaign for what would become the most collectible iteration of the Air Jordan line. The IIIs were the first to bear the mid-flight Michael Jordan silhouette logo, The Jumpman, an image that was actually staged for the ’84 Olympics. Commercials for the shoe starred a young Spike Lee as Mars Blackmon, a goggled uberfan who speculated why Jordan was the best player in the universe. It was neither the short socks nor the epic dunks, Blackmon was sure. It had to be the shoes!

In response to this hugely successful campaign, Reebok launched the absurdist and ultimately unsuccessful “Let U.B.U.” campaign. The ads featured nonsensical individualism—a vacuuming ballerina, a beekeeper-suited bridesmaid—while a vaudevillian voiceover read non-sequentially from what I would much later discover was Ralph Waldo Emerson’s “Self-Reliance”: “Who so would be a man, must be a non-conformist . . . To be great, is to be misunderstood . . . To believe that what is true for you in your private heart is true for all men—that is genius.” Although widely dismissed as an expensive dud, I found the ads magical. The words took my sixth-grade breath away.

I memorized the panegyric by copying down what I could decipher each time I saw the ads. Our television was often just on, so when I heard the opening violins of the commercials, I dashed into the living room to scribble down a few more lines. Some of it I didn’t understand. “A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds” felt counterintuitive—wasn’t being consistent good?—but the uplifting, self-congratulatory counsel was familiar. Much of the rap music I heard preached the same ego and self-esteem.

Emerson’s advice like “insist on yourself, never imitate” echoed much of the inspirational self-love that permeated early hip-hop: “Strive for improvement / be your own guide / follow your own movement” rapped Heavy D in “We Got Our Own Thang.” He was nearly indistinguishable from Emerson later in the song: “Stay self-managed, self-kept, self-taught / Be your own man / don’t be borrowed / don’t be bought” embodied the Emersonian emphasis on the self as the truest source of judgment. You could find the divinity of the self all over too: on Gangstarr’s “Royalty,” Guru asserted that regardless of what you were up to “your essence was divine son / let it shine son,” sounding very much like a transcendentalist. In his self-aggrandizing songs, Guru spoke to my secret heart the same way the “Let UBU” commercials did. For me, rap lyrics were interchangeable with the empowering music of Emerson’s language. Both fit into the list of things that made me feel tough and cool.

Sneakers were on high on that list, too, a near shorthand for tough and cool. At my high school, everyone stepped carefully, eager to neither step on someone’s sneakers nor have one’s own sneakers stepped on, since both missteps required a confrontation. Ideally, sneakers were immaculate. I kept spot remover in my locker to keep the synthetic suede on my Sauconys bright. My senior year, I wrote a short play we performed in drama class, Grimm’s “The Elves and the Shoemaker” fairy tale reimagined with elves who left behind Jordans in the night.

For my family, the go to spot for sneakers was the Foot Locker outlet in Langley Park, Maryland where we lived, just outside of D.C. My parents immigrated to Langley Park during the crack epidemic, when D.C. became the “murder capital” of the country and the border suburb of Langley Park took on the accoutrements of an inner city. My brother and I observed the proliferation of the drug trade all around, some of it even designed for us: the ice cream truck sold plastic bubble gum dispensers shaped like plastic pagers, toy versions of the beepers dealers wore. It all fit into one look, the hustler hip-hop aesthetic: big jeans, gold chains, expensive sneakers.

On Gangstarr’s “Royalty,” Guru asserted that regardless of what you were up to “your essence was divine son/let it shine son,” sounding very much like a transcendentalist.In the sixth grade I did not wear expensive sneakers. I wore “bobos,” the pejorative for no-name tennis shoes we purchased at a bargain shoe store where my father would urge me to consider thick-soled nurse’s shoes.

“A lot of cushion,” he would say, aiming the bottom of the sexless shoe at me. “Very comfortable.”

When I made a face he would examine the shoe anew. Ugly?

One day that spring, while my brother picked out a pair of stylish but affordable Pumas at the Foot Locker Outlet, I idly examined a pair of white Avias with toothpaste blue piping. Avias had just been purchased, unbeknownst to me at the time, by Reebok, but I had never heard of them. Scottie Pippen would sport them briefly before eventually moving to Nike, but they mostly made women’s running shoes.

“You like this one?” My father asked. He headed to the registers with them.

At $49.99, they were nearly four times what my footwear normally cost. I must have looked like the shoemaker in Grimm’s story, stunned to suddenly have in possession, shoes one doesn’t deserve.

I almost told my father to stop. Fifty dollars almost paid for a week’s worth of groceries. I eyed the blue-green digits on the register when we checked out at the grocery store, noted which items we might return to the shelves if the bill was too high.

“Remember this at Christmas time!” My father called over his shoulder, his indication he understood the gravity of the moment. “Birthday time also!” he added.

The next morning when I wore my new Avias to school, my feet felt like suns, glowing orbs on which I float-strutted. I had on my best outfit: fake gold doorknocker earrings and a yellow “Someone in California Loves Me” t-shirt, coarse as a dishtowel. I looked my best. I planted myself on the classroom floor, my freshly sneakered feet thrust out as I rummaged unnecessarily through my book bag. Check out my new shoes, everybody.

Light-skinned Anthony Templeman, a short, rat-faced boy who wore gauzy Sergio Tacchini tracksuits always had something to say.

“Dag,” he said, raising his eyebrows with genuine appreciation, “Alis finally got some nice shoes.”

I stopped my rummaging.

Finally?

Finally.

Finally meant my previous not nice shoes had not gone unnoticed. People noticed. My peers noticed. Boys noticed! It was the first time I considered that my poverty might not only be apparent but integral to how others viewed me. I was, whatever other demographic identity, plainly poor to boot.

For weeks after, I stewed in this new information. Dragged into a certain socio-economic self-awareness, I felt a fresh shame about my appearance, a development that would flower in the next few years as it does for most young women. Loathing for my weight, my glasses, the terrible clothes I had too few of, furled out from that day, when the abrupt, irrevocable visibility of my poverty was revealed to me, forever rooted in my first pair of name brand sneakers. It was the shoes after all.

I would not rebound until I became a noisy cliché in college, armed with Malcolm X and poverty credentials that were an authoritative currency with my middle-class classmates. But the process began with Emerson’s words as much as with the bombast of Public Enemy and Angela Davis. I would not reevaluate him from a critical stance until graduate school, where he would reappear as culprit of all sorts of patriarchal crimes and evincer of empty self-importance, an affluent white man canonized for aphorism more than anything else.

I do not dispute any of those estimations, but in the crucial weeks after Anthony Templeman’s offhand-come-revelatory comment, Emerson’s “Self-Reliance” was nourishment as well as armor. Even as his self-glorifying prose now frightens me, imagined in the hands of undergraduates who do not need anyone else assuring them of their genius, I think of myself at twelve: brown-skinned, ugly, and suddenly visibly poor. I should have felt inadequate. But walking into that classroom every morning after in the very shoes that I had wanted, and that had undone me, I told myself “to take” myself, as the Emerson voiceover intoned, “for better, for worse” as was my “portion.”

So what if I was poor? Poverty was my portion; it was “the plot of ground” “given” to me to “till.” Emerson, like all the rappers I listened to, made that seem like steady ground on which to step.

Previous Article

Falling in Love with Malcolm X—and His Mastery of MetaphorNext Article

What Do We Really Mean By'Women's Fiction'?