Discovering China's 16 Million Comrade Wives

On Expectation and Sexuality in the World's Most Populous Country

In addition to being a mediocre brand of Japanese dairy sold widely in China, Suki is the name of Beijing’s most sought-after bikini waxer. She has become such a household name among the community of foreign females in Beijing that she often comes up in conversations at cocktail parties. When two women discover that the same hands are tending their topiary, something magical happens, whereby like sugar wax to the pubis, they instantly bond. Part of this has to do with the shared intimacy of knowing that the same woman is plucking their privates, but also, I suspect, because of Suki’s intriguing story.

Before becoming the door-to-door wunderkind of bikini waxing, Suki worked in the spa of one of Beijing’s most upscale boutique hotels. (Beyoncè and Victoria Beckham stayed there when they were in town.) She had a solid following of regulars, but the working conditions at the hotel, despite its plush appearance, were deplorable. After one of her clients suggested she go solo and offer in-home beauty services at a fraction of the spa price, Suki handed in her notice at the spa and valiantly launched her own little waxing start-up.

Fastidious in her work, Suki removes wax as if conducting an orchestra. With little more than a medium-sized champagne-colored knockoff Longchamp tote containing all of her supplies, she shuttles between the homes of her clients, leaving everyone she touches marvelously glabrous. The quality and convenience of her services have led her to rack up a small fortune—much more cash than her husband, a barber, is able to bring home. According to Suki, he is very supportive of her job, and even helps pack up her supply bag on his days off. The only complaint she has is the very transient nature of her clients—mostly female expats who are in Beijing for a limited period of time. Though she is always getting new clients through enthusiastic word-of-mouth referrals, with her daughter approaching middle school and the rising cost of her educational expenses, Suki began asking around for suggestions on how to build a steadier client base. She was surprised to learn that many of her female clients had the same advice: expand waxing services to include men.

Despite the rather progressive nature of her profession, Suki still teeters on the line toward conservatism. She’s from a small village in Shanxi province, and most of her life in Beijing is completely unfathomable to her family. “I tell my parents that I do facials,” she says, which she also does, although the lion’s share of her business comes from Brazilian waxes. Without getting too deep into the depilatory routines of Chinese women, I think it’s safe to say that Brazilians are far from the norm. I’ve been in gym locker rooms where women have been aiming blow dryers at their nether regions, and many men, I’ve had confirmed, do the same. But gay Chinese men—well, they might just be a gold mine for Suki, if she were up for the challenge.

“Oh,” she says, perplexed, when I mention this to her. “But where to find them? I’ve never met one.”

This surprises me, though it shouldn’t. The hotel where Suki was formerly employed occupies what may very well be among the gayest 500 square meters in Beijing. Its bar is the setting for a weekly gay happy hour that’s like The Wizard of Oz meets Madonna. In warmer months when the terrace is open, the often impeccably coiffed men who gather there emit such a strong mix of cologne onto the surrounding sidewalk, I’ve come to call it Beijing’s Duty-Free. “Maybe my husband could help me with this?” Suki asks cautiously, still unsure of the viability of this idea, though certainly interested in the monetary prospect of it.

Suki is not the only person in China who doesn’t understand homosexuality. Yet despite common misconceptions that may stem from a dubious record with regard to human rights and personal freedoms, China is not—at least on the surface—especially hostile to gay people. Beijing, in particular (which, of course, is not representative of greater China) is home to several gay bars. Depending on the political climate of the times, a large-scale event (like the Mr. Gay Pride Pageant in Shanghai) might be shuttered by the government, but on the day-to-day club scene, the gay community appears to face minimal policing from the powers that be.

The home front, however, is a different story entirely. Though the World Health Organization removed homosexuality from its index of mental disorders in 1990, homosexuality was officially classified as a disease in China until 2001. Depictions of homosexuality on television have long been banned in China, but starting in July 2017, the China Netcasting Services Association (CNSA) prohibited the portrayal of “abnormal sexual lifestyles” in Internet video content—a category that, in the eyes of the censors, includes homosexuality. Needless to say, homosexuality is still not very well understood, especially by parents who are all very keen to have their children married, but not to the extent that they’d tolerate their child marrying a member of the same sex, if that were even possible. The curious thing about the parental opposition to gay marriage, however, is that it is as much moral or ethical as it is a matter of losing face; it’s seen as something that mars a family’s reputation and jeopardizes its ability to function as part of the social order.

To get Suki’s new business revving, I introduce her to my friend Leo, a gay Chinese man who has been with his partner for three years. “My mother knows I’m gay,” he tells us, “and she kind of accepts it, but she still keeps hounding me to marry a woman. When I reminded her that I like men, she said, ‘I don’t care what you like, just give me a grandchild!’” She went so far as to suggest that Leo get married and have a baby with his partner’s older sister (a leftover woman), as if that would lead to the creation of one, big, happy family.

The content of this conversation is rocking Suki’s world. “There are gay men married to straight women?” she asks me later, in private. “Sixteen million of them,” I tell her. She looks at me wide-eyed, realizing that her market potential is much larger than she had ever imagined.

*

Zhang Beichuan is the sexologist at Qingdao University who calculated the 16 million statistic based on his 20-plus years of demographic research centered on China’s gay community. He’s not a gay activist nor gay himself, but explains that this area of research interested him because there was so little information available, and very few people working in it. He tells me that in the 1990s, an estimated 40 percent of the gay men he interviewed reported having suicidal thoughts. Over time, that percentage dropped to 20 percent, but Beichuan’s work has shown a consistent rise in the depression rates of another group: China’s tong qi or “comrade wives”— straight women married to gay men.

Despite their rather friendly moniker, most tong qi women don’t often live happy lives as wives. Very few are aware of their husband’s sexuality before marriage, something that, when it is eventually discovered, comes as a hard blow. By Zhang’s estimates, 90 percent of tong qi are depressed, 70 percent report having experienced long-term emotional abuse, 40 percent experience suicidal thoughts, and 20 percent have experienced repeated physical violence from their husbands. His numbers are based on a sample of 150 tong qi wives who had been married an average of four years, with an average age of 31. He also tells me that 80 of the women in his study discovered their husbands were gay as the result of intervention from a private detective. Roughly three women knew of their husband’s homosexuality before their marriage, but didn’t see it as an issue. “I thought I could ‘fix’ it,” said one of his sources, who, Beichuan points out, was an accomplished college graduate.

Because the stigma surrounding homosexuality in China is still so strong (except for the nightclub scene, as mentioned earlier), many comrade wives don’t know what to do when they discover they’re married to a gay man. Christy, for one, was in complete shock.

I’d known Christy well over two years before she told me about her previous marriage. Over this time period, we’d become good friends, and she’d even been the inspiration for Chaoji Shengnu, a playful cartoon series that I created. Most of our meetings were high-octane ones. We’d sometimes catch up quickly at events or locations where she was in charge of the PR—fashion shows, nightclub anniversary parties, and boutique and gallery openings. Often, these events were attended by gay men—models, designers, art patrons, and owners of over-the-top entertainment establishments. She often joked that she knew more gay men than straight ones, but she had never mentioned that she’d once been married to one. Christy met her former husband at a very young age, and according to her, it was love at first sight. “He was so sweet and handsome, I married him within three months of meeting him.” Their relationship had been chaste prior to marriage, but following a few complications with small cysts on her ovaries, Christy’s husband decided that the couple should stop being intimate until she was feeling better. Her doctor never told her to stop having intercourse, but as she was very young and somewhat startled by her condition, she decided to err on the side of caution. As Christy’s sabbatical from sex approached the two-year mark, however, she became suspicious. Each time she attempted an advance on her husband, she would be dismissed, and he’d bring up the cysts on her ovaries, which had long ceased to be a matter of concern. “I started to think there was another woman,” she recalls. “So I started checking his phone.”

No leads.

“I always thought of him as someone very simple,” explains Christy, “happy to just hang out with the guys.” It wasn’t until he left a chat program on his laptop open one day that she discovered his penchant for teenagers.

“My first reaction was total disbelief,” she said, “but then I started connecting all the dots from our years together and things started to make sense. There was absolutely nobody I could tell though—my parents would be outraged, and he was begging me not to out him. I decided to treat it like an affair, telling him we could still guo rizi, or ‘spend our days together.’ He agreed most penitently, telling me he would give up his ‘dirty habit.’”

Christy wanted to believe her husband, but she didn’t trust him, so she kept an eye on his computer. There was no activity for two months, but then his lascivious chats with young men picked up again. Feeling distraught and helpless, she took refuge in the anonymity of the Internet, where she tracked down a support hotline for women in her situation.

Xiao Xiong’s was the comforting voice on the other line that helped Christy cope with everything she was experiencing. Christy believed that she had “made” her husband gay because she was unattractive and inattentive to his needs. Xiao Xiong’s counseling allowed her to understand that women don’t make men gay. She listened, advised, and gently gave Christy the courage to peaceably end a marriage that was depleting her sense of self-worth, her confidence, and her happiness.

It’s only a few minutes into my conversation with Xiao Xiong before I realize that she’s also married to a gay man. The conditions of their marriage, however, are radically different from Christy’s. Xiao Xiong is a lesbian, and she and her gay husband have what is commonly referred to in China as a xing hun or a “cooperative marriage.” Though Xiao Xiong vehemently opposes marriages in which gay men are dishonest about their sexuality and wed straight women, she happens to be one of China’s greatest facilitators of marriages between openly gay men and lesbian women looking to tie the knot with a member of the opposite sex in order to keep up appearances. In 2007, Xiao Xiong created the first QQ group for gay men and women in the market for a fake spouse. “Like any marriage,” she explains, “both parties must really get to know one another and be very clear as to what their objectives are. But if men and women are honest with one another and have common goals and values, these arrangements can actually end up being a good way of mitigating the marriage pressure they face.”

To date, over 300 “cooperative marriages” have taken place between couples who met on the site, and Xiao Xiong is so familiar with the spouse-selection process, she practically has it down to a formula. The five most important questions a couple needs to discuss before deciding to get married are:

Will we live together? (she says not many couples do)

Will we have a child? (she says most Northerners don’t want to have any children, but Southerners are more likely to want one)

Will we pool our finances? (usually couples living together may want to share finances)

Will we get a real marriage certificate? (many couples—especially those who opt to be childless—prefer to get a fake marriage certificate, so they are not legally bound to each other. These fake certificates, often prepared by special agencies, cost around 200 RMB, (US $30), or 25 times the price of a real one)

Will we get a divorce? (some couples marry only temporarily to appease their parents, and then divorce after a year or two; other people have a big wedding for their parents to enjoy, then come out of the closet a few years later, once they feel they’ve done enough for their family and are entitled to do something for themselves)

Xiao Xiong reports that, overwhelmingly, couples decide to enter cooperative marriages due to pressure from their families. “Some parents even know their kids are gay, but they still want them to go through the hoops,” she explains.

In Xiao Xiong’s case, her parents have no idea that she is a lesbian. Marrying a gay man was simply the least confrontational way to address her obligation to get married. Her parents spent 200,000 RMB on the reception, and still don’t know that the woman helping Xiao Xiong into her wedding dress was her partner.

She maintains a friendly relationship with her husband, but not a close one. “We each have our own lives,” says Xiao Xiong, who lives with her partner. “We basically just see each other for meals over the holidays with our families,” she says. “We don’t communicate much otherwise, but my husband is great. When my mom got sick last year, he came with me to take care of her for a few days. I’ve done the same for his parents in the past.”

__________________________________

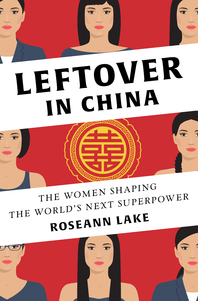

Excerpted from Leftover in China by Roseann Lake. Copyright © 2018 by Roseann Lake. Used with permission of the publisher, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Roseann Lake

Roseann Lake is The Economist’s Cuba correspondent. She was previously based in Beijing, where she worked for five years as a television reporter and journalist. Her China coverage has appeared in Foreign Policy, Time, The Atlantic, Salon, and Vice, among others. She lives between New York City and Havana.