Today is a mortal equinox for the Fish family. It’s been six months since Papa Julie died, and six more will pass before Grandma Gertrude does too. With Grandma Gert having recently moved into an assisted living home, the surviving Fishes come to take inventory of their brick house in Hempstead. It’s in this driveway that the infamous Yellowstone trip began. Ask any Fish about that trip and they’ll tell you how Papa Julie drove his sons all the way to Wyoming, for all of one night’s camping, and then proceeded to drive them all the way back to Long Island.

Ask any of those same Fishes and they’ll tell you why Papa Julie didn’t fly commercial: The late Julius Fish fought the Nazis.

He’d sat in the nosecone of a B-25 bomber plane, angling trajectories of destruction upon German outposts in Italy. He was a bombardier whose family knows of his life on the Allied base in Corsica, but little else of his wartime experiences—until finding his war journal, a leather-bound diary tucked away amid the farrago of items collected over nearly a century.

Lieutenant Julius Fish served with Catch-22’s author, Joseph Heller, who was also a bombardier stationed on Corsica, and had told his family that he would often share details of his missions with his pal Joey when they were back on base. The journal provides a shocking peek inside Papa Julie’s intimacy with violence and valor—and is only the beginning of a search for how deep this contradiction went.

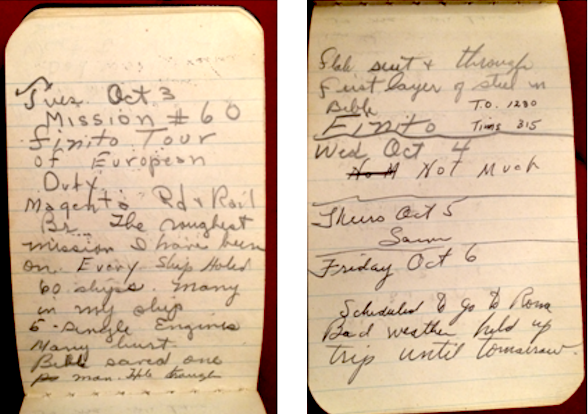

From Julius Fish’s war diary.

From Julius Fish’s war diary.

Papa Julie’s war journal betrays him immediately, save for the fact of it; that he’d ever written about his time in the war, even to himself, is difficult to grasp, even for his own son. He so seldom spoke of the war that his grandson Jonathan tried to document the times he did. In one particularly colorful video, Papa Julie regales his family of how he and his comrades had gone about attaining better provisions. With breathtaking nonchalance, he describes a trading syndicate encompassing the Mediterranean and beyond.

In Sicily he traded cigarettes for enormous pears, which the stall owners claimed grew from the ashes of Mount Rosa. When fellow comrades asked where he’d gotten them, Julius replied, “Gimme your allotment of cigarettes and I’ll give you all of Sicily.” One day a group of high-ranking officers joined his squadron for a meal in their bivouac. One of the officers quipped, “What are you guys eating, Spam?” To which Julius responded, “Spam is for the animals. We eat meat!” He’d gone on to tell the officers how he procured meats from Africa and used Italian prisoners as personal cooks. “They could take that meat and make things—they were geniuses!”

Even the strongest democracies require independent thinkers to conscientiously object during critical moments.For those who’ve read the novel, this tale is eerily suggestive of Catch-22’s Milo Minderbinder. More than a clever mess officer, Milo is an unrelenting profiteer, a caricature of the capitalist spirit. Beginning with simple goods, Minderbinder builds a trading network that covers the entire Mediterranean region. Milo’s greed is seemingly limitless; he’s eventually charged with treason for selling bombing rights to Axis powers.

But Papa Julie wasn’t a mess officer. He hadn’t a rapacious bone in his body. And the word “treason” would have to be brutally neutered before it could even be remotely applied to him. Sure, he might’ve mentioned his friendship with Joseph Heller during the war, but no, he hadn’t influenced any Milo Minderbinder. He could barely talk about the war at all, much less sell bombing rights to his enemies. And this is why the war journal is so jarring to read—why it takes a few moments for the content to sift past the shock of his words being applied to the war.

More treasures, exhumed from the same box, draw their attention. Photos, correspondence, bombardier tools, medals. Yet the most precious of them will turn out to be that journal, which charts each mission’s bomb targets, the day’s weather, casualties—even what movie they watched upon their return to base. It explains the contact paper, which Bob and Francine found in the attic; he’d built a dark room in his squadron’s bivouac, having felt an axiomatic need to document his war experience. Not knowing whether he was going to live, perhaps that was the point.

At this equinox, new questions have only illuminated the full impact of his passing. Anything more is too much to absorb. It won’t be for another few months that Papa Julie’s grandson, Jonathan Fish, will embark on the project of a lifetime: using these primary sources as proof that his grandfather’s WWII story is known by millions, but has somehow eluded those closest to him; that he was inspiration for none other than Captain John Yossarian, the defiant protagonist of Joseph Heller’s classic novel, Catch-22.

*

Historically romantic notions of war have declined in direct correlation with the effectiveness of modern warfare. By the end of the Great War, quixotic notions of glory and adventure all but vanished. And yet another tradition of war would be broken by the end of WWII: never again would such clear lines separate good and evil; never again would war be fought so simply, with this country wearing that uniform, and that country fighting for this side. From the moment the Wehrmacht took Belgium, much of the world knew which side it fell on, if not when it would fight. The world simply watched as Nazi divisions performed maneuvers before hundreds of thousands of Reich citizens, every last one of them applauding their awesome might.

By the time FDR declared war on Japan, American citizens were ready to change their lives for the war effort. Two thousand people had been murdered on US soil, in broad daylight; whether a zealous patriot or a willing participant, it was expected that you’d go and fight, help manage the fighters, or work in the factories. Draft-dodging, isolationism, anti-war protests—in 1942, these had become marginal terms in the American discourse. Some draftees did apply for conscientious objector status, but this was only legal recourse.

*

Imagine it’s April 1st, 2011. You’re a veteran of the 340th bombardment group, which took off from the Allied airbase in Corsica, Italy during the latter stages of WWII. Today, you’re making the trip out to Long Island, where fellow veteran Lieutenant Julius Fish lies on his deathbed. It’s been years since you’ve seen anyone from the 340th, let alone your own squadron, and exactly 66 since you’ve seen Julius. You meant to make an effort, but for life and its limitless demands on your attention. And to be fair, Julius never attended the reunions.

At the door, you commiserate with Mr. and Mrs. Fish, who say, “Please, call us Bob and Fran.” In the living room, you concentrate on the mourners, who greet you and your bomber jacket with uniform warmth and admiration, sad at its edges. To cheer up Julius’s grandson, Jonathan, you corroborate stories. You mention how Julius’s mission protests sure did influence that book of Joseph’s—that Catch-22. But Jonathan must’ve misconstrued your grin. He smiles as well, but shakes his head. “Papa Julie would’ve appreciated a date-appropriate prank,” Jonathan might say.

I think your evidence is overwhelming; your grandfather was clearly the principal inspiration for Yossarian’s narrative adventure.Now imagine that a friend from another squadron, whose tent was 20 paces from yours in Corsica, calls to inform you that Julius went in his sleep last night. It’s April 2nd, so you know the time’s passed for audacious jokes. (Though you also remember Julius, how he’d gone to great lengths to pull one on you.) You lament with your fellow vet, share a few memories of the wily nosecone pilot, and thank him for the call. A few months later, you find yourself wondering what became of Julius after the war. You dial Long Island and catch his grandson on the phone. Jonathan’s confused by your call, but when you say you’re a fellow veteran of the 340th, he begins reciting mission passages as though leading a Talmudic chavruta—primary sources that suggest his Papa Julie had inspired Heller’s eventual protagonist for Catch-22, Captain John Yossarian.

Of course, you’re likely not a former bombardier of the 340th. But you weren’t born yesterday; you can imagine the difference a few months can make. And what’s becoming clearer every day is that Lieutenant Fish wasn’t just a comrade of the 340th bombardment group’s 488th squadron, fighting alongside none other than Joseph Heller; they were also good friends, evidenced through shared addresses in their journal and pictures of them and the rest of the “Brooklyn Boys,” as well as Francis Yohannan, whose namesake—and namesake alone—was Heller’s inspiration for Captain John Yossarian’s.

In a nearby tent just across a railroad ditch in disuse was the tent of a friend, Francis Yohannan, and it was from him that I nine years later derived the unconventional name for the heretical Yossarian… in no other respects was he [Yohannan] like Yossarian…

–Joseph Heller’s memoir, Now and Then

Furthermore, Yohannan made the military his career. As noted in Francis Yohannan’s obituary, “Yohannan racked up more than 9,000 air hours in B-25s, B-36s during the 1950s, B-52 bombers carrying hydrogen bombs during the 1950s and 60s, including the Cuban missile crisis in 1962, and Phantom fighters during the Vietnam War.” His decision to continue to serve in the military after WWII places him at odds with Yossarian’s odious feelings towards the military.

More importantly, the attic trove is quickly revealing itself as evidence of this enigmatic connection. Galvanized by Papa Julie’s war journal, Jonathan’s research has led him to a paper by Daniel Setzer, titled Historical Sources for the Events in Joseph Heller’s Novel, Catch-22. As suggested by its title, Setzer’s paper details the actual events from which Heller drew inspiration for his novel; and access to raw data gives Jonathan an idea.

During these early stages of discovery, Jon and his wife, Michelle, go on vacation to Vieques, Puerto Rico. Like many New York professionals, Jon isn’t wont to luxuriate, even though he’s earned and paid good money to do exactly that. So between Jurassic-like Jeep rides into jungle brush, he assumes an arduous intellectual ordeal: matching Papa Julie’s mission logs with Joseph Heller’s own and Catch-22’s, whose 50th anniversary edition from Simon & Schuster includes an appendix of Heller’s organizational chart for the novel.

Before “catch-22” became a colloquial phrase used to describe any paradoxical dilemma, it was born from only one: Captain John Yossarian’s mentally stable desire to discontinue flight missions would only be satisfied by a diagnosis of mental instability. Heller’s chart organizes this dilemma along two vertical axes. Down one side are mission limit levels—i.e. the increasing number of missions commanded and flown—while down the other is a timeline of the war itself. The columns between the axes are headed by each character from the novel, thus aligning their fictional experiences with those of real events throughout the war.

From Setzer’s paper, Papa Julie’s, and Heller’s organizational chart for Catch-22, Jon creates his own matrix of matching data. The resulting equivalences more than corroborate his suspicions.

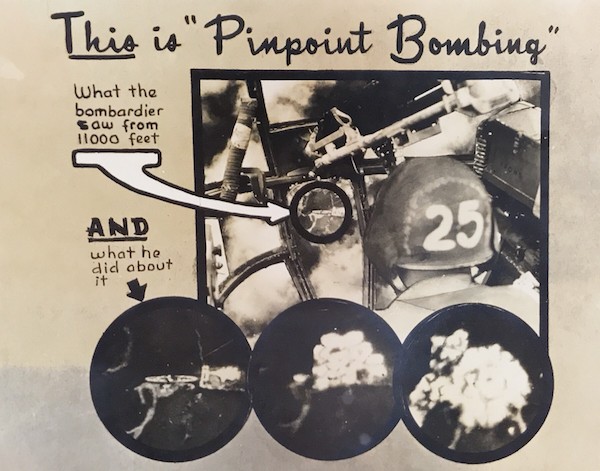

Above is a portion of Jonathan Fish’s comparison between Catch-22’s organizational chart and Joseph Heller’s and Papa Julie’s war journals. Notice that Lt. Fish and Joseph Heller were both sent on the same mission (Fish’s 56th and Heller’s 51st) to take out the Taranto, an Italian war cruiser. This mission is featured very accurately in Catch-22, and Lt. Fish and the 340th Bombardment Group received a unit citation for sinking the cruiser. The picture below shows Lt. Fish lining up the sight on the Taranto. Published in the 340th Bombardment Group Squadron Book, titled This is “Pinpoint Bombing”, the photo is among those donated to Brandeis University. Heller describes his actions that day in Now and Then, “I was relieved to discover myself assigned to one of the planes in a chaff element… We carried no bombs. Because we carried no bombs, we could go zigzagging in at top speed and vary our altitudes. Because we carried no bombs, I shrewdly deducted that there was no need for a bombardier. Therefore, after priming and test-firing the machine gun in the bombardier’s compartment in the nose of the plane, I resolved to sit that mission out—literally.”

Jon’s father used to tell him to ask Papa Julie about his friend Joey Heller. This was far before Jon could comprehend Heller’s fame, not to mention Catch-22’s non-linear narrative. By now, however, Jon’s read the book, along with many apposite analyses and publications. He’s also gathered enough evidence to suggest that Papa Julie was more than just a friend to Joseph Heller—but it’s the next find that blows the door wide open.

At first glance, Catch-22’s Doc Daneeka falls just short of deus ex machina. Given the opportunity to unburden Yossarian of his obligation to fulfill ever increasing mission limits, he pronounces the novel’s eponymous problem: that he’d “be crazy to fly more missions and sane if he didn’t, but if he was sane he had to fly them. If he flew them he was crazy and didn’t have to; but if he didn’t want to he was sane and had to.” To which Yossarian famously replies, “That’s some catch, that Catch-22.”

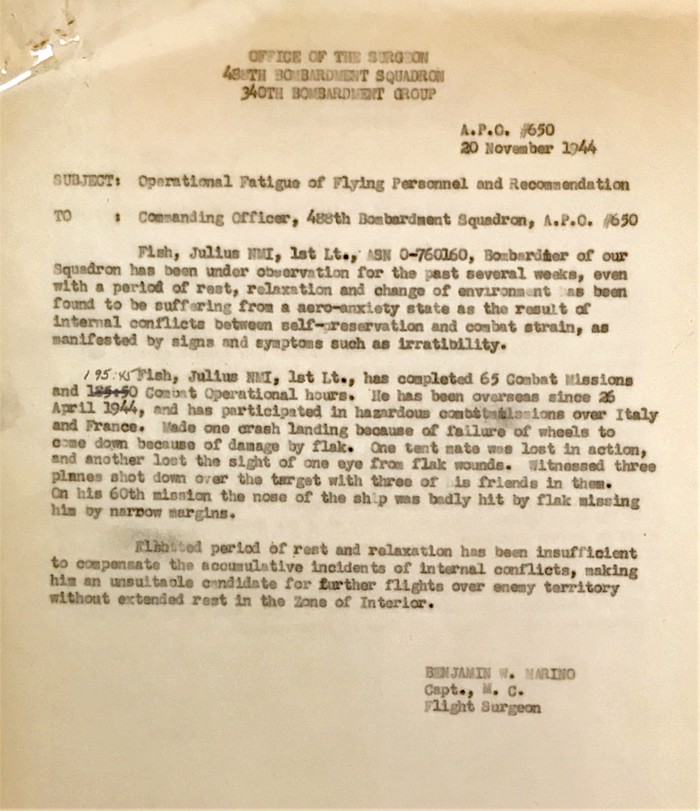

Heller later identified one Dr. Benjamin Marino—whose son, Robert Marino, created a web page about his own path to discovery—as inspiration for Doc Daneeka (noted in Heller’s letter to Simon & Schuster, which he’d written ahead of publication to stave litigious issues that may have arisen from the connection between his characters and real-life people). Sure enough, back from vacation, Jon returns to the attic trove and finds a note written by Dr. Marino. The note declares that Lt. Fish “has been found to be suffering from an aero-anxiety state as the result of internal conflicts between self-preservation and combat strain, as manifested by signs and symptoms such as irritability.”

Note from Dr. Benjamin Marino, explaining the diagnosis of aero-anxiety.

Note from Dr. Benjamin Marino, explaining the diagnosis of aero-anxiety.

Juxtaposed with Jon’s excitement is the realization that his grandfather, who seldom spoke of the war, was once throttled in this paradoxical vise of patriotic duty and personal welfare. At the center of his struggle lay what is now a widely-accepted trauma. Somewhere in the middle of that diagnostic cladogram stood Jon’s grandfather, semi-erect, of the speciose genus “Aero-Anxiety”; while at either end of this evolutionary timeline are the ancestral “Shell-Shock” and the presently emergent “Post Traumatic Stress Disorder” (which, as Dillon Carroll mentions in a piece titled “How Doctors Discovered PTSD,” published by The Washington Post, wasn’t added to the DSM until 1980). It’s now all too clear why Jonathan’s grandfather refused to fly commercially—another affliction shared with Heller himself.

*

“If you can keep your head, when all about you are losing theirs…” opens Rudyard Kipling’s poem, titled If. Even the strongest democracies require independent thinkers to conscientiously object during critical moments. Catch-22 demonstrates the gray area between legality and morality, and that society should honor the heroes who recognize when leadership fails to navigate that gray area appropriately—those who refuse to allow themselves to be the tool manipulated by the hand of the state.

In fact, ask any psychology student or hobbyist about the Milgram Experiment and watch their faces cloud over with its harrowing implications on human nature.

Beginning in 1961, Stanley Milgram, of Yale University, embarked on an experiment that would determine just how the Third Reich was able to instill such malevolence in its citizens. He began by hiring confederates (those complicit in the experiment’s procedures but who pretend to be participants) to perform either one of two tasks: the first type of confederate would order participants to provide electric shocks to people they couldn’t see, but whom they could hear all too well across a basic partitioning; while the second type of confederate pretended to receive the electric shocks that the participants applied. The results were, paradoxically, as shocking as they were expected. Sixty-five percent of the participants obeyed orders to the point of “murder,” having applied increasing voltages and endured victims’ harrowing screams until the electrocutions were met with fatal silence.

In a very real way—that is, in the human way of contradicting desires and motives—Lieutenant Fish fought the institutions that manipulate reality to serve its aims.Famously, on December 24th, 1914—the first Christmas of WWI—the French and German trenches emptied out into No-Man’s land to share the holiday spirit. But Christmas 1914 wasn’t a vestige of war’s historical traditions of romance and honor. It was a modern anomaly, a rare instance of soldiers trying to remind themselves why their enemy deserved the shells being hurled at them from countless paces yet with terrible precision.

To this day, global military brass instill the thrills and glories of war. From booths set up in high school cafeterias to commercials of soldiers coordinating perfect pincer moves, millions of young men and women still march into barracks with romantic notions of adventure. Joseph Heller felt it himself when enlisting:

A group of us enlisted—we had nothing better to do… for those of us Americans in that stage who weren’t harmed physically or damaged emotionally by military service, the war came along at just the right time. It put an end to our confusion and ambivalence, took most powers of decision out of our hands, and swept us into a national endeavour considered admirable and just.

–Joseph Heller, Now and Then

Heller goes on to describe his standard of living in Corsica as “vastly improved.” Yet it was only inevitable that he confront the war’s deleterious constancy. To assuage this darkened mood of soldiering, the military establishment dangles a number like a carrot: number of months on the front line; number of missions flown; number of tours of duty. Once that number is hit, finally, you can go home.

Except they raise the number. Then they raise it again—and again, and again, until you realize that you’re not going home until they want you to go home. For the 340th bombardment group, what had initially been a 25-mission limit was increased by steady increments of five until bombardiers like Lieutenant Fish were faced with flying their 65th mission (and beyond for many others). The latest Stop-Loss policy, decreed by George Bush during the Iraq War, is nothing else if not a legislative euphemism for forced service, not all that much different from the relentless raising of mission limits at center of Yossarian’s plight.

But there is another side to this story. To think war is categorically unjustifiable would be, to this point in history, naïve at best. Hostility and desire are part of our biological makeup, and when presented with a Hitler or an Assad, what choice is there but to combat him? Similarly, to think that nations can wage wars without drafting manpower—i.e. without forcing civilians to fight—is also a chimeric notion. Military bureaucracy is thus confronted with the difficult task of fighting on two fronts, one against the enemy and another at home. As with sociopathy and valor, during wartime, it’s difficult to suss out which is which.

Catch-22’s prescience lies in the culmination of this effect, from Vietnam through to Iraq, Afghanistan, and Syria today. Joseph Heller wrote about a phenomenon before it’d become a known phenomenon; that is, having attested to neither Yossarian’s resentment toward his commanders nor the missions those commanders had doled, Heller sensed something that he himself had not seen.

Or had he? Is it possible that he saw something, extrapolated it, combined it with his own experience, and then wrote a prescient novel? Is this not the mode of writers, this exact process of conflated experience and imagination?

In Heller’s memoir, Now and Then, he refers to Yossarian as the “incarnation of a wish,” which implies his desire to have exhibited Yossarian’s understanding of their dilemma. Why wouldn’t he have looked up to an elder Fish, who was 26 and had his own business when entering the war? While Julius Fish had enlisted to dictate where he’d be assigned when he knew his number would be called, Heller had enlisted to not be in Brooklyn.

“We were all friends,” Papa Julie told his family, “…the Jews stuck together… You were either from Texas or from Brooklyn.”

Regardless, at 19 years of age, Heller couldn’t have possibly predicted he’d one day write a novel so powerful that American soldiers in Vietnam would carve into their helmets a prophetic rallying cry: Yossarian Lives!

*

Jonathan Fish has come a long way from documenting Papa Julie’s tale about the trading syndicate. What was once a fond if farfetched memory of Papa Julie’s story has now, within the context of Jon’s discoveries, added inches to this lengthening Fish story. With each new piece of evidence, the distance between Jon’s hands increases; the chances that Papa Julie was a major inspiration for Yossarian are now about yea big, and growing.

He will reach out to various professors and experts, starting with Professor Steve Whitfield of Brandeis University. Professor Whitfield’s written extensively on the changes in war sentiment between WWII and Vietnam, often citing Yossarian’s heroism throughout his works. Jon arranges a meeting with Professor Whitfield and Head Archivist, Sarah Shoemaker, at Brandeis’ library. Among the massive archive labeled “The Heller Collection” are pictures of Lieutenants Fish and Yohannan; pictures that were photocopied from the 340th Bombardment Group’s yearbook; pictures that Papa Julie owned in the original, which Jon currently provides as corroboration.

Photo from Lt. Julius Fish’s collection, whose photocopy is part of the Heller Collection at Brandeis University. Lt. Yohannan is on the far left, while Lt. Fish stands on the far right.

Photo from Lt. Julius Fish’s collection, whose photocopy is part of the Heller Collection at Brandeis University. Lt. Yohannan is on the far left, while Lt. Fish stands on the far right.

The mountain of evidence culminates in Jon’s blog, YossarianLived.com, which correlates his grandfather and Yossarian. Seeking to place a paper by the same title, he reaches out to Jofie Ferrari-Adler, executive editor at Simon & Schuster and caretaker of the Joseph Heller estate. Ferrari-Adler connects Jon to one Professor Jonathan Eller, Chancellor’s Professor of English at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis. Professor Eller has written volumes on Catch- 22’s publication process and edited the appendix materials to the 50th Anniversary Edition of Catch-22 (published in 2011), and is quick to validate Jon’s evidence as strong enough to presume his grandfather as Yossarian’s major influence.

I think your evidence is overwhelming; your grandfather was clearly the principal inspiration for Yossarian’s narrative adventure, and his reaction to the trauma of unrelieved aerial combat…. I’m grateful for your work to preserve these new treasures.

–Professor Jonathan Eller, IUPUI

For all the evidence exhumed from the attic trove, Jon’s initial confrontation with the perils Papa Julie once faced imbues his quest for knowledge; e.g. that such an adventurous man had been so afraid of flying as to drive them from Long Island to Yellowstone. There are countless such idiosyncrasies and stories that stoke Jon’s increasing motivation to understand how Papa Julie maintained composure throughout these dire circumstances.

One such story is Catch-22’s sequence regarding the Ferrara Bridge. A key medium of transport for Axis powers, American bombers can’t make tail or bone of how to hit it. A ninth attempt fails, and Yossarian, against orders, returns to try again. Though successful, Yossarian’s rogue bombing run costs him the life of a comrade named Kraft. Now the bomber brass is in a pickle; punishing Yossarian is an implicit admission that they’ve lost control of their crew. So instead, he’s awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross—thus maintaining squadron morale.

Using his grandfather’s war journal and Heller’s organizational chart, Jon realizes that Papa Julie targeted Ferrara multiple times—and was also awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for his efforts. As per the writeup of his Distinguished Flying Cross:

Second Lieutenant Julius Fish… has been awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for extraordinary achievement in an attack upon a railroad bridge near Villafranca, Italy… On July 15, after releasing his bombs with precision accuracy… a direct hit from enemy ground fire exploded one 1,000-pound bomb just below Lieutenant Fish’s formation.

Then, from Catch-22:

…He [Yossarian] buried his head in his bombsight until his bombs were away; when he looked up, everything inside the ship was suffused in a weird orange glow. At first he thought that his own plane was on fire. Then he spied the plane with the burning engine directly above him.

The DFC award continues, noting that Lieutenant Fish “skillfully guided his pilot, avoiding known gun position, safely back to base after one engine, compass, and the radio were destroyed by the fragments. Lieutenant Fish displayed great skill and resourcefulness in navigating his course with the aid of a pocket compass.” (Now’s a good time to note that Papa Julie was a navigational savant who prided himself on calculating routes and traffic patterns. Years later, without knowing that his son Bob had gotten a GPS for the car, he was shocked to hear a disembodied voice parroting his perfect directions.)

Not until the 1980s was a legitimate ombudsman assigned to the war’s operations (Sam Zagoria of The Washington Post, who also passed on April 2nd). It’s doubtful that Zagoria had a chance to dig into activities within the 488th squadron, which was within the 340th Bombardment Group. Yet had he done so, he would’ve found discrepancies, between journal accounts and orders, that certainly would’ve corroborated Lieutenant Fish’s.

Through these primary sources, Jon sees what it means to operate the nosecone of a B-25 bomber. How treacherous flak envelops your bomber like a thousand exploding thistles. How, at the height of this mayhem, you must steady the plane from the nosecone, line up your target site, and deploy your bombs. How you bide your time between ceaseless missions necessary not only to win the war, but to get the hell out of the war. How you write letters purposefully devoid of this fear. How you return home and keep this enigma locked up inside until you’re gone and can no longer guard the safe.

As per the 487th Bomb Squadron’s war journal, reacting to the stand-down order after the squadron successfully hit Ferrara: “Too much sweating isn’t good for anyone and the boys are really entitled to a day off after sweating out the flak and enemy fighters protecting Ferrara.”

Through these primary sources, Jon sees what it means to operate the nosecone of a B-25 bomber. How treacherous flak envelops your bomber like a thousand exploding thistles.Indeed, Jon’s quest has become far more than an interest or passion. It’s his duty to show the world what Papa Julie means to it. To learn more about his grandfather through Yossarian.

To develop a heretofore unimaginable compassion for Papa Julie’s composure throughout the struggle. To see why Heller had called Yossarian the incarnation of a wish; why Professor Whitfield once mentioned of Yossarian, during Brandeis’s 50th Anniversary panel on the Heller collection, that he “…is not running away from his responsibilities, but running towards them… That is what is so ethically striking and psychologically intriguing about Catch-22… the creation of a character who is somehow able to transcend the demand, the imperative upon him placed by a legitimate organization, fighting a legitimate war for a justifiable cause.”

*

Papa Julie was fond of bawdy jokes. There was the one he liked to tell about the Jewish man’s chauffeur, who was excited for Rosh Hashanah because that’s when Jews blow the shofar. Less blemish than beauty mark, the memory of Papa Julie’s ribaldries keeps him alive to his bereaved family, and are indelibly linked to the man who wanted little more than to love his family and nurture his carpet business.

However, belief in a man’s absolute virtue redacts his full range of experience, and we know what redaction can accomplish. Only from the gamut of life’s trials could Julius have learned and grown to become the man he was. In rare cases, however, the truest version of a man’s life surpasses his legend.

In a very real way—that is, in the human way of contradicting desires and motives—Lieutenant Fish fought the institutions that manipulate reality to serve its aims. Just as the NFL anthem protests aren’t anti-American, Yossarian’s protests weren’t anti-war. Like so many of those who kneeled on Sundays, Papa Julie had the strength to hold contradicting truths; that the country he loved wasn’t upholding its promises to its personnel, forcing pilots to risk their lives past their agreed-upon mission limit. As he wrote in his war journal for what was supposed to have been his last (60th) mission:

Finito Tour of European Duty… The roughest mission I have been on. Every ship holed. 60 ships. Many in my ship. Many hurt. Bible saved one man. Hole through his flak suit + through first layer of steel in Bible. FINITO.

In June 2018, US immigration officer Antar Davidson was ordered to tell two sibling children that they couldn’t hug—a six- and a ten-year-old, unsure whether they will see their parents again, whether they themselves will remain together. Two siblings whose reasons for holding onto hope were fading fast were told they could not embrace for even a short time. In officer Davidson’s own words, “They called me over the radio. And they wanted to translate to these kids that the rule of the shelter is that they are not allowed to hug,” he said. “And these are kids that had just been separated from their mom—basically just huddling and hugging each other in a desperate attempt to remain together.” Davidson demonstrated his objection to this level of cruelty by quitting his job, choosing to sacrifice his own well-being so that he could look at himself in the mirror and know that he wasn’t going to be a pawn in a political game that stretched far beyond him.

Not for the first time, after Lt. Fish had hit his last mission limit, he wrote in his journal, “Better get back to Brooklyn soon”—he was then ordered to fly five more times. Knowing he could no longer rely on the military to uphold its promises, after an abortive 61st mission, he cited bad weather; then a bad engine and bad weather (62nd); bad weather (64th); turned back (65th). Then he was granted another furlough, this time back to the States, and his tour ended shortly after that. The relative dearth of detailed information surrounding Lieutenant Fish’s last abortive missions and his abruptly granted furlough, whether ironic or just plain weird, is certainly intriguing; that such negative suggestion can loom so tall as to nearly overshadow the hardest of evidence. More importantly, however, is the fact that, like Antar Davidson, whatever Julius Fish had decided, he’d done so with the intent to maintain his integrity.

Before the Fishes began sorting through Julius’s house back in 2011, they’d seen all of one photo placing him at the scene of WWII’s European theater. Thanks to Jon’s research, they now know that the photograph was over Spezia Harbor—and so much more. But the knowledge that Papa Julie had internalized nearly the entirety of his experience, and chose not to relive its expression in any form, including Catch-22 itself, is nothing short of onerous, both in an anachronistic sense for Papa Julie, and in an inexorable sense for the family he’s survived by.

Perhaps it’s not such a far leap, then, to credit his story, sublimated through Heller’s literary classic, as a preliminary step toward acceptance. For without understanding impacts beyond what we can see—e.g. that sweet pears often come from illicit trade syndicates; that progress often comes at the cost of protest—we wouldn’t be the humans we are, who live, perhaps, to discover.

Papa Julie’s desire to simply return home and start a family is reflected in Jon’s desire to reincarnate that wish. The wider work of placing his grandfather’s story at the forefront of American letters is yet to be done, and he hopes that this writing can act as a preliminary step toward doing so. But the hardest part has been accomplished. Rather than his story being swept under a rug of inspired characters, Jon and his family have undergone a sort of personal therapy, listening to Papa Julie from afar, and though unable to see him, they can now understand what he did to protect his country—on both fronts.

______________________________

With research and contributions by Jonathan Fish.