Did Shakespeare Write Hamlet While He Was Stoned?

Sam Kelly Explores the Potential Influence of Cannabis on the Bard’s Prolific Literary Output

William Shakespeare was in danger of being canceled. He was a big fan of mind-altering drugs—especially cannabis. But the Church of England looked down on live theater because of its “unwholesome” moral content and was keeping an eye out for plays to shut down; plus, city officials had to approve plays before they could be performed within the city limits. So, if Shakespeare had dared to admit publicly that he smoked cannabis, it might have ended his career.

That’s right, Shakespeare was a stoner. I’m not making this up—they found the evidence in his backyard. Back in 2001, some anthropologists got permission from a museum to borrow twenty-four clay pipe fragments that had been dug up in the small town of Stratford-upon-Avon, where Shakespeare used to live. Using state-of-the-art forensic technology, the anthropologists discovered cannabis residue on eight of them—including several from Shakespeare’s backyard garden—that dated back to the late 1500s/early 1600s, around the time he actually lived there.

If Shakespeare had dared to admit publicly that he smoked cannabis, it might have ended his career.

Professor Francis Thackeray has written extensively about the findings. This guy is legit: he’s got a PhD from Yale University, and he personally participated in the forensic tests. He says they also found traces of coca leaves (that’s where cocaine comes from) and myristic acid (a hallucinogenic drug derived from nutmeg) on some of the pipe fragments. Unlike the cannabis residue, however, the coca leaves and myristic acid weren’t found directly in Shakespeare’s garden (although they were found nearby)—but it opens the door to the tantalizing possibility that Shakespeare might have been into all sorts of mind-altering drugs.

Technically, the evidence is circumstantial. Pipes with cannabis residue were dug up in Shakespeare’s garden, but that doesn’t necessarily mean Shakespeare is the one who put them there. (Hey, maybe they were planted in his garden by Sir Francis Bacon, right?) So Professor Thackeray, being a smart and thorough scientist, decided to obtain conclusive proof. He asked the Church of England for permission to exhume Shakespeare’s corpse and run the necessary tests in order to answer, once and for all, the question of whether Shakespeare smoked pot. Guess what the church said. No way, not a chance, that’s not a question they want answered.

But if Shakespeare was a stoner, he faced a thorny dilemma. On the one hand, he enjoyed using drugs and wanted to include depictions of drug use in his plays. On the other hand, he didn’t want the church to ban his plays for immoral content. So how did the greatest writer of all time resolve this dilemma?

The answer is he wrote about drugs, but without saying what they really were. His plays are filled with characters who ingest all manner of fantastical pharmaceutical concoctions. For example, in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Oberon, the king of the fairies, tells Puck to fetch an exotic magical flower so that he can extract its juice to formulate a love potion—but it’s pretty obviously opium. We know for a fact that Shakespeare was familiar with opium because he says as much in Othello (emphasis added):

Not poppy, nor mandragora,

Nor all the drowsy syrups of the world,

Shall ever medicine thee to that sweet sleep

Which thou owedst yesterday.

Similarly, in Romeo and Juliet, the young heroine, Juliet, is distraught because her parents are forcing her to marry someone other than Romeo. She begs the friendly Friar Laurence to help, and what’s his genius idea? That she drink a sleeping potion that will knock her out so completely and convincingly that the whole world will believe she’s dead for two days. Juliet actually takes his creepy advice. Basically, she roofies herself—Shakespeare might just as well have been talking about GHB.

But the fact that Shakespeare wrote about love potions, sleeping potions, and other fanciful elixirs isn’t conclusive evidence. It’s the nature of dramatic storytelling: writers invent peculiar concoctions to give their characters a reason to act in ways they wouldn’t normally act. That doesn’t prove Shakespeare was a drug user. You can scour through every single one of his plays looking for passages that might or might not refer to drugs, but you won’t find a Da Vinci Code-like secret that unlocks a hidden drawer containing a signed confession from William Shakespeare admitting that he smoked cannabis.

Although one of the sonnets he wrote comes pretty close. Professor Thackeray, the same anthropologist who performed the pipe analysis, points to Shakespeare’s Sonnet 76, which talks in part about the act of writing (emphasis added):

Why is my verse so barren of new pride,

So far from variation or quick change?

Why with the time do I not glance aside

To newfound methods and to compounds strange?

Why write I still all one, ever the same,

And keep invention in a noted weed,

That every word doth almost tell my name…

The wording in Sonnet 76 is pretty convincing. Many scholars believe the “noted weed” in which the author finds “invention” is a reference to cannabis and its ability to stimulate creativity. Some also think the phrase “every word doth almost tell my name” is a sly reference to the fact that “shake” (as in Shakespeare) is another word for cannabis—specifically, the scraps left over after cannabis buds have been plucked and packaged.

But what about “compounds strange”? The sonnet says a writer whose writing has become “barren” could potentially turn “to newfound methods and to compounds strange,” but the author suggests he has chosen not to go that direction. Does that mean Shakespeare wasn’t a drug user? Not necessarily. Professor Thackeray believes the passage could mean Shakespeare used cannabis (“a noted weed”) for his creative inspiration, and chose to avoid using other, more dangerous drugs, such as cocaine, because they were “compounds strange” that could prove harmful.

As you might guess, Shakespeare scholars tend to get a bit defensive when someone starts to suggest that maybe the Bard enjoyed cannabis. They feel like it’s an attempt to undercut his achievements—but that isn’t the case at all. I’m not saying if Shakespeare was smoking pot when he wrote Hamlet, it somehow makes the play less great—or worse, that anyone who was smoking pot could have written it. Heck, writers have been using cannabis for four hundred years since Shakespeare died, and so far no one has managed to come close to replicating the man’s genius.

To put a twist on one of his most famous lines: I come to praise Shakespeare, not to bury him. He was a uniquely gifted writer who told stories in a compelling and enjoyable way. Basically, he was the Walt Disney of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Everyone loved his plays. He didn’t write only for kings, queens, nobles, and other snooty rich people. Sure, they attended his shows and appreciated his work—but his most enthusiastic fans were the lowly commoners who flocked to the Globe Theatre to occupy the standing-room-only section. They were known as “groundlings,” and they’d hoot and holler at his ribald jokes and raunchy banter. It was almost like having a mosh pit at his plays.

The stories he told weren’t necessarily original. Shakespeare borrowed plotlines from books and adapted folktales from other cultures—Hamlet, for example, is based on an old Scandinavian tale. His real genius lay in retelling these stories in a way that appealed to a much broader audience than the original source material—just like Disney didn’t create the plots of Cinderella, Mulan, and The Little Mermaid, but instead took existing source material and transformed it into audience-pleasing, world-spanning megahits.

He’s still regarded by many as the greatest writer who ever lived. If cannabis helped him get there, it doesn’t tarnish his legacy.

His real gift was language: puns, rhymes, clever wordplay, and memorable turns of phrase. If he were alive today, Shakespeare might be a rapper because of how easily the words seemed to flow from his mind. Do we have cannabis to thank for that? Maybe, at least in part. Many authors (and rappers) have used mind-altering drugs to enhance their creative process and boost their productivity—and no one can deny that Shakespeare was insanely productive, given that he wrote 37 plays and 154 sonnets in the span of his twenty-three-year career.

In addition to writing plays and sonnets, Shakespeare created words themselves. He’s credited with adding roughly 1,700 words to the English-language lexicon. While the total number is probably exaggerated—experts believe some of the words were already being used in everyday conversation and Shakespeare was simply the first person to write them down—the fact remains that he invented at least a few hundred new words.

But wait, how were audiences able to follow what the characters were talking about if he kept making up new words? This was part of Shakespeare’s genius. Like the plots of his plays, the words he invented weren’t cut from whole cloth; they were adapted from familiar source material.

One of his favorite tricks was to take two existing words and join them together, as he did with “barefaced” and “bloodsucking.” At other times, he took a noun and turned it into a verb (“elbowed”). He changed nouns into adjectives (“catlike”), verbs into adjectives (“revolting”), and verbs into nouns (“excitement”). He also liked to add prefixes, taking words like “formal” and “educated,” and giving them a twist, creating “informal” and “uneducated.” Or he’d add a suffix, creating words like “disgraceful” and “distrustful.” When all else failed, he’d take a Latin word and anglicize it a bit, yielding words like “tranquil” and “articulate.”

The result is that Shakespeare’s plays are filled with words that never existed before, and yet their meaning was immediately clear. And yes, a few of his new words sound like they might have been invented by someone who was high at the time—words such as “trippingly” and “moonbeam,” and “zany” and “swagger.” In fact, Shakespeare was the person who first coined the word “addiction”—but he also created the word “transcendence.”

So did Shakespeare smoke cannabis? The scientific evidence suggests he probably did, but this doesn’t make him any less of a genius. He’s still regarded by many as the greatest writer who ever lived. If cannabis helped him get there, it doesn’t tarnish his legacy. Maybe his real genius was knowing what worked for him.

__________________________________

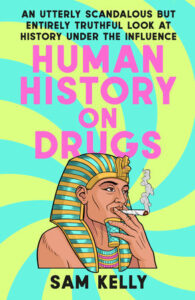

From Human History on Drugs: An Utterly Scandalous but Entirely Truthful Look at History Under the Influence by Sam Kelly. Copyright © 2025 by Samuel Ezra Kelly. Published by Plume, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Sam Kelly

Sam Kelly, a history grad from Stanford University, is on the autism spectrum and his interest and passion for history has become an almost physical compulsion. He loves to dig up forgotten and weird stories from the past and spends hours uncovering every last stubborn detail. As a deep believer that history can be as exciting as any Marvel movie, Sam aims to—whether on TikTok or through a book—make history both engaging and accessible to all. Human History on Drugs is his first book.