Did Medgar Evers' Killer Go Free Because of Jury Tampering?

Jerry Mitchell Revisits a Dark Episode in the Struggle for Civil Rights

In my years of living in Jackson, I had driven down Medgar Evers Boulevard many times. Yet I knew almost nothing about the namesake for this four-lane thoroughfare. To learn more, I drove to the Mississippi Capitol, constructed on the grounds of what had been the state’s first prison. I hiked up the marble stairs until I reached an office for reporters covering the legislature. From their high perch, they could watch lawmakers traipsing up and down the corridors, huddling in hallways with lobbyists and sneaking into committee rooms for conversations.

When I walked into the Capitol Press Room, I saw veteran journalist Bill Minor clacking his fingers on his Underwood manual typewriter, spitting out a column. He had been covering Mississippi since the 1947 funeral of one of its most racist senators, Theodore G. Bilbo. The son of a newspaper Linotype operator in Louisiana and a lifelong Democrat, Minor had long viewed himself as a champion for the little guy. While working for the New Orleans Times-Picayune, he came to the forefront in 1947 when the New Yorker wrote a profile on him, stunned to learn that Minor’s story on the governor’s secret police group known as the Mississippi Bureau of Investigation had failed to make national headlines.

After his time with the Times-Picayune, he turned The Capital Reporter, a collection of community announcements, into a hard-hitting investigative publication. Syndicated columnist Carl Rowan wrote, “Mississippi is a better state and Jackson a better city because Wilson F. ‘Bill’ . . . Minor has been socking it to fast-and-loose bankers, crooked politicians, the Ku Klux Klan and others.”

I sought Minor out because he had known Medgar Evers and reported on his work from the mid-1950s to the early 1960s. At the screening of Mississippi Burning, Minor had brought up Evers’s name.

Months before the US Supreme Court ruled in the 1954 desegregation decision, Brown v. Board of Education, Evers became one of the first black applicants to the all-white and all-powerful University of Mississippi School of Law. He had hoped to become a lawyer and perhaps run for Congress one day, but white Mississippi was up in arms. When Mississippi attorney general J. P. Coleman questioned where Evers would stay while attending the segregated university, he replied, “On the campus, sir. I’m very hygienic. I bathe every day, and I assure you this brown won’t rub off.”

The law school rejected his application, and Evers consulted with the NAACP on whether to sue. Impressed with the young professional, the NAACP hired him instead as its first full-time field secretary for Mississippi. From his start in December 1954, he put 40 thousand miles a year on his car, helping revive NAACP branches, organize new ones, and register African-Americans to vote.

Outsiders painted his home state as hopelessly cursed, but Evers believed Mississippi would be a fine place to live once the enemy of hate had been defeated. “I don’t choose to live anywhere else,” he told Ebony magazine. “There is room here for my children to play and grow, and become good citizens—if the white man will let them.”

No matter where he went, however, threats of violence followed. He had been followed so many times he had lost track. That was one reason he had bought his Oldsmobile 88. It had a V-8 engine so powerful it left most cars behind. The speedometer would change colors, depending on his speed. On some dark nights across the Mississippi Delta, his dashboard glowed red as he floored it to escape those hell-bent on harming him.

On June 12th, 1963, just hours after President John Kennedy told the nation that the grandsons of slaves were still not free, Medgar Evers was assassinated.

Evers’s name began appearing on KKK “death lists” almost as soon as he took over the NAACP in Mississippi, his telephone ringing at all hours with threats. Some messages were short and emphatic: “We’re going to kill you, nigger.” Others were longer, but no less frightening, describing how they planned to torture him.

In May 1963, he became even more visible after the FCC cleared the way for him to respond to the white mayor’s criticisms of the NAACP, which the mayor called a “northern outside group.” Evers told the television audience that more than half the NAACP members were southerners. Whether Mississippi chooses to change or not, he said, “History has reached a turning point, here and over the world.”

After his speech, he led civil rights marches and boycotts in downtown Jackson. More death threats followed. “They said they’re going to kill me,” he told CBS News. “They said they’re going to blow my home up. They said I only had a few hours to live.” As he edged closer to his fateful end, he told The New York Times, “If I die, it will be a good cause. I’m fighting for America just as much as the soldiers in Vietnam.”

On June 12th, 1963, just hours after President John Kennedy told the nation that the grandsons of slaves were still not free, Evers was assassinated. It was after midnight when Evers pulled into the driveway of his Jackson home. He grabbed a bundle of T-shirts that read “Jim Crow Must Go” and opened the car door. After he had shut the door and stepped forward, a soft-nosed Winchester bullet smashed into his back. The slug struck him above his right kidney and mushroomed, breaking two ribs before tearing through a lung. Blood and flesh showered the windshield.

He collapsed onto the concrete, gasping for air. The bullet continued through Evers’s body and shattered a window in the house. His wife, Myrlie, had been dozing inside and now sprung awake. As Evers struggled to drag himself toward the house, Myrlie and the Everses’ three children, Darrell, Reena, and Van, dashed outside. They saw the blood and screamed.

“Daddy, Daddy!” Reena yelled. “Please get up, Daddy!” He never did. Too much damage had been done.

*

Byron De La Beckwith.

That singsong, six-syllable name bounced around in my brain. It didn’t take much reading to learn that two all-white juries had failed to agree on a verdict for Beckwith in 1964. It didn’t take much more reading to learn that, by all appearances, he had gotten away with murder.

Old newspaper stories and magazine articles portrayed him as the lone, obsessed assassin, determined to kill the NAACP’s number one man in Mississippi. The case against Beckwith had certainly been convincing. His high-powered rifle had been found near the murder scene, complete with his fingerprint. Witnesses placed his white Valiant, with his law enforcement–like whip antenna, near the scene. Two taxi drivers testified that he had asked directions to the NAACP leader’s home a few days earlier.

When FBI agents arrested him, they found a circled cut around his right eye, and Beckwith admitted it had come from firing his rifle. If all that weren’t enough, his words provided a motive. “The NAACP, under the direction of its leadership,” he wrote in a letter to the Jackson Daily News, “is doing a first-class job of getting itself in a position to be exterminated!” In his defense, Beckwith offered an alibi. Two policemen testified he was more than 30 miles away, in Greenwood, a half hour from the time Medgar Evers was killed in Jackson. Beckwith maintained his .30-06 Enfield rifle had been stolen days earlier.

Jurors deadlocked 7–5 in favor of finding Beckwith not guilty. At his second trial, jurors deadlocked again, this time even closer to acquittal. After that, prosecutors dropped the case.

Beckwith went free from jail and returned to the Mississippi Delta a hero. A sign across a Delta bridge proclaimed, “Welcome Home, Delay,” a sight that brought him “tears of joy.”

After he arrived home, his best friend, Gordon Lackey, swore Beckwith into the White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, according to FBI records. The pair were so tight that Jackson police had investigated the possibility that Lackey, a crop duster, had flown Beckwith down to Jackson for the assassination.

In 1967, Beckwith made an unsuccessful run for lieutenant governor, telling voters he was “a straight shooter”—a line he delivered with all the subtlety of a sledgehammer. His over-the-top campaign, promising “absolute white supremacy under white Christian rule,” finished with 5 percent of the vote.

When the trial took place, he said Beckwith had made a show of it. After a defense lawyer handed him the murder weapon, he took aim, causing one juror to duck. Beckwith relished the attention and greeted visitors such as former major general Edwin Walker, who had been arrested for helping lead the 1962 insurrection at Ole Miss that ended in two deaths. Minor also said that Beckwith didn’t pay a dime for his defense. The white Citizens’ Council picked up their charter member’s entire tab, hiring three council members as lawyers: Hardy Lott, Hugh Cunningham, and Stanney Sanders, who happened to have been the same district attorney who failed to get a Greenwood, Mississippi, grand jury to indict two of Emmett Till’s killers for his 1955 abduction, despite their confession to the crime.

Possible jury tampering? Now that was a story. And it could call into question the legitimacy of Mississippi’s handling of the Medgar Evers murder.

The journalist believed Beckwith was guilty, but the all-white jury failed to convict him. Minor said prosecutors certainly weren’t helped by the fact that Ross Barnett, who had served as Mississippi’s governor until days before the first trial began, attended the trial and showed his support, shaking hands with Beckwith.

I shook my head at this revelation. How could the jury interpret this as anything other than a signal to acquit Beckwith?

This information fit with what Lawrence had told me, about the Sovereignty Commission assisting Beckwith’s defense. I shared what I had found so far with Minor, and he became angry. “It’s an outrage the state of Mississippi was prosecuting and on the other hand was trying to subvert the efforts.”

*

Did these clues have the power to pry open the Medgar Evers case? I had no idea, but I knew I needed to follow them. They led me back to Erle Johnston, who continued to put his best spin on the Sovereignty Commission’s dark deeds. He said he would be willing to talk with me as long as my story mentioned his new book on the commission.

I asked him why a state agency, led by the governor, would have aided an alleged assassin. He assured me they never would have gotten involved in the investigation, but when Beckwith’s second trial took place, there was someone on the list of prospective jurors who had the same last name as agent Andy Hopkins at the commission. Johnston said that the defense lawyer contacted Hopkins and asked if he was kin, to which Hopkins replied that he might be a distant cousin.

But the Sovereignty Commission agent didn’t stop there, I knew—Hopkins helped Beckwith’s defense lawyers check out all the potential jurors. When I objected, Johnston defended the agent’s actions. “That was right in 1964. Everything was tense,” with spy agency officials wondering if these potential jurors “were connected with people coming down south.”

Mississippi’s segregationist spy agency prepared a complete report on the prospective jurors, identifying them by occupation and social affiliations, he said. “One said he was a member of the [white] Citizens’ Council. The rest may or may not have been.”

He said Hopkins had gathered all the information through telephone calls.“It was just like looking up a committee of the Chamber of Commerce.”

I questioned him about this. “If an investigator was making calls, trying to find out as much as he could about the potential jurors, wouldn’t he contact their bosses, family members, or others?”

He acknowledged that was possible.

“Couldn’t that have had an influence on the jury?”

He insisted the commission had zero influence on jury makeup. If these white men were denied a spot on the jury, he said, “it wasn’t on account of us.”

After talking with Johnston, I shared his explanation with my best source on the Sovereignty Commission, Ken Lawrence, who replied, “That’s absolute bullshit. Of course what the commission did affected the jury and affected the trial. Let me read you more from the report.

“Two potential jurors are each referred to as likely to be a ‘fair and impartial juror.’ Here’s what the commission report says about another juror: ‘Believed to be Jewish. No further information available.’ What do you think that tells you?”

*

Possible jury tampering? Now that was a story. And it could call into question the legitimacy of Mississippi’s handling of the Medgar Evers murder. Still, before I turned in my story, I wanted to see if I could reach Beckwith himself for a comment. If only I could find him.

In 1987, then–Jackson Daily Newsreporter Willie Raab had conducted a telephone interview with Beckwith in which the latter had urged “white-only, Christian rule” for the nation. At the time, he was living in Signal Mountain, Tennessee, just outside Chattanooga. When I dialed directory assistance, the operator found no listing for Beckwith.

I called Raab, hoping he had hung on to the phone number. No luck. The sheriff ’s office there was no help, either.

I telephoned the Chattanooga Times and explained to the operator that I was trying to find someone who might have a number for Beckwith. The next thing I knew I was talking to Johnny Popham, the legendary reporter who put 50 thousand miles a year on his green Buick covering the South for The New York Times. In his Tidewater Virginia accent, Popham told me he didn’t have Beckwith’s number. But he promised to check around.

When I checked back days later, Popham still knew nothing.

Without any further leads, I went ahead and turned in my story to my editor John Hammack. After reading it, he messaged me back on my computer, “Great story. Damn. It’s a shame we can’t get a hold of Byron.”

__________________________________

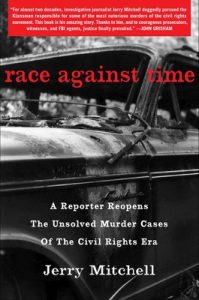

Excerpt adapted from Race Against Time: A Reporter Reopens the Unsolved Murder Cases of the Civil Rights Era. Used with the permission of the publisher, Simon & Schuster. Copyright © 2020 by Jerry Mitchell.

Jerry Mitchell

Jerry Mitchell has been a reporter in Mississippi since 1986. A winner of more than 30 national awards, Mitchell is the founder of the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting. The nonprofit is continuing his work of exposing injustices and raising up a new generation of investigative reporters.