Did Mark Z. Danielewski Just Reinvent the Novel?

The Author of 'The Familiar', on his 21,000-Page Book

Mark Z. Danielewski is deep into the forest. Tired and a bit tense, he navigates through the prickly pine needles and the rustling leaves, mining the tugging roots and the looming canopy for the connections only his mind sees. Though the forest comes from his own imagination, it seems to act independently, as if attempting to enfold him in its many layers.

Outside the forest, where I am, it’s raining. Despite the downpour, though, the world positively bustles. A little girl barrels into the torrent to save a hurt cat. A young gang member heads out on an assignment. A pair of scientists hides out from an ambiguously malicious organization. A taxi driver waits for a fare. An enigmatic billionaire enlists the help of a poverty-stricken recovering drug addict. Life, in other words, abounds.

Or, to put it as Danielewski does: “It’s a very bizarre conversation we’re having because, in some way, you’re talking to me about Volume 1 [One Rainy Day in May], and I’m talking to you about Volume 2 [Into the Forest]. And already there’s this weird kind of layering where I realize I should talk more about the metaphor of rain which is so important in Volume 1, and yet I am in the forest. So there’s a whole array of pine needles and forest stuff that’s coming, and yet we are still kind of talking about the same thing.”

This same thing is The Familiar, Danielewski’s most ambitious narrative undertaking yet, which is saying a lot. The author of the cult classic House of Leaves and the radical Only Revolutions isn’t exactly known for his simplicity. Yet The Familiar makes those previous works look like exercises. First of all, the 880-page Volume 1: One Rainy Day in May is the first of twenty-seven. As in, a potential of over 21,000 pages. As in: what the fuck does he think he’s doing?

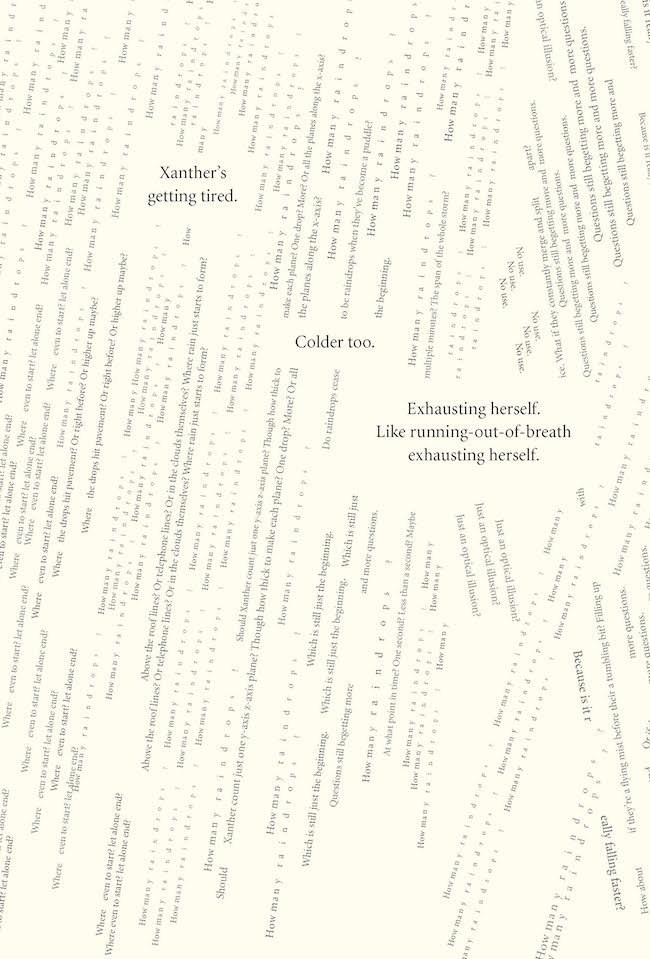

Moreover, The Familiar: Volume 1 is a Ulysses-like narrative of a single day. The pages jump back and forth between at least nine characters, and each chapter is written in starkly different prose, in different fonts, and in varying formats. The movements and thoughts of each character are meticulously traced; even their internal rhythms are accounted for. Take, for instance, Anwar, a computer programmer who’s taking his daughter Xanther to get a dog. His text, then, comes out like this:

In fact, Xanther’s appointment isn’t until 10 AM [10:10 AM actually {the big surprise not until later that afternoon <at 3 PM <<in Venice (to the tune of $20,000)>> >}].

Whereas the Armenian cabbie’s voice reflects his broken English:

Shnorhk give courtroom another once around. Almost as bad as pisser. There mirrors scratched by gangs and drunk hearts. Here faded blue plastic seats. Woodpanel walls stained dark where accused rest heads. Behind judge, U.S. flag, California flag, bathed in fluorescent green. Like clotted stuff Shnorhk cough up.

Unlike Ulysses, however, The Familiar takes place all over the world: Los Angeles, Texas, Mexico, and Singapore. And it also seems, judging purely from Volume 1, that these disparate narratives will collide in a monumental way as the series continues.

Right now, deep into the second book, Danielewski’s not thinking about his grand literary design. He’s only thinking about logistics. “I have an enormous amount of finished pages that are due on Monday,” he tells me, “and more in another week. And there’s a very intense back-and-forth going on right now between myself and Pantheon, my editor, copyeditors—those responsible for, you know, making sure that the art comes out the way we want it to. And all of this is happening as Volume 1 begins to make its first appearance. And that’s what I was referring to when I said I’ve never been in this place before. Usually the book is long-since done, and the brain is kind of wandering off into other outskirts, unknown neighborhoods, but I know what neighborhood I’m in.”

So mired is he in Volume 2 that he’s developed a kind of psychic connection to it. For instance, the other day a glitch in his computer deleted four pages of the manuscript. “I’m pretty meticulous about archiving various drafts,” he says, “so it wasn’t a setback, but I did have this sense of vertigo over lunch when I realized that I had somehow detected, almost instantly, that out of 880 pages, four, non-consecutive, were missing. Like, my eye caught in the thumbnails that something was a little off.”

All of which makes it kind of difficult to get extract profile-worthy information from him. I mean, the dude is so fucking tangential—in a brilliant and fascinating way, to be sure, but sometimes it takes some acrobatics to follow his mind. For instance, I asked him what he was like as a kid, and he starts telling me about the time, in Provo, Utah, he decided to construct a “corn mash still,” from which one can make moonshine. “You have to remember,” he says, “this was in high school in Provo, Utah, in the early 80s. So it was 99 percent Mormon. My friend was a devout Mormon, and yet somehow this seemed like a very good idea to explore.”

It’s a funny story, and also one that speaks to the way Danielewski thinks about literature. He says his itinerant childhood (his family lived in Spain, Germany, Switzerland, England, as well as numerous places in the U.S.) was about “exploring what the literature was, exploring the actual mechanics, and I think actually I’ve always really liked the way you can read something and then bring it to life, whether it’s a recipe, whether it’s origami, whether it’s directions.” Imagining the creator of such wildly inventive books appreciate literature for both its content and its real-world applications isn’t a hard leap. In fact, it makes perfect sense: someone who loves taking the lessons of literature into the material world must have some desire to put some of those materials back into books, right?

It’s not that the book is living, but in the presence of the reader, the reader feels suddenly alive to her own promise. And that’s what a book can awaken. And I think the only way that that happens is if the writer is really putting it on the line.

But once Danielewski mentions the notion of giving directions, he’s off on a beautiful tangent about “the art of directions.” “You meet individuals who could tell you so clearly how to get somewhere,” he says. “Then you realize that that was almost more important than where you were heading. That you were suddenly in the presence of a stranger who could tell you where the market was in such a manner that you would find it, versus someone you love who’s incredibly intelligent but is absolutely incapable of giving directions to a certain place. And how much is communicated in that art form, which has now been replaced by GPS and whatnot.”

I say something about how a person’s directions will also characterize the geography in between as well. And he’s all over that.

“And they’re telling you about themselves, too. And there is an intimacy there because they are considering who you are, and they’re considering what is the best way to communicate to you, how to find this place. Is it through names on street signs? Is it through the amount of time it will take to drive to a certain place, or is it about distance? There are a lot of observations that are made and there is something wonderful and binding about that, whereas when you’re on MapQuest or whatever it is, you are actually learning how to respond to this thing, which has no interest in taking you as an individual into account.”

I must admit: I feel a little in over my head.

* * * *

Mark Z. Danielewski was born on March 5, 1966 in New York City. (The middle initial ‘Z’ is not a pen name, as many have assumed, but he won’t tell anyone what it is until he’s married. He’ll tell his wife and then everybody else.) His father Tad Danielewski fought in WWII as part of the Polish Underground. After immigrating to the states in 1948, he launched an impressive career in filmmaking. He married three times, and with his second wife Priscilla Decatur Machold, he had a daughter Anne and a son Mark. Anne went on to become the acclaimed singer Poe (who would eventually produce a record based on House of Leaves).

Because of his war experience, Danielewski’s father “carried with him these sort of palpable anxieties that not only could a city vanish in a moment but an entire country.” So young Mark grew up with a heightened sense of not wasting time, especially when it came to reading and learning. “There was this understanding,” he says, “that there was much to be learned out there.”

This, of course, prompts another wonderful little rant about reading and language and time: “I have to feel that as soon as I’m on the page, I’m cheating time. That’s one of the great gifts of language is that suddenly I’m participating in something that is granting me years on the moment. And that can fly across all sorts of borders and genres. There’s just a sudden, you know, shimmer in the text and you realize that you are privileged to, in a few hours experience, something that exceeds those hours. Great literature almost seems to exceed time itself.”

Danielewski, for his part, studied literature at Yale, and did post-graduate work at USC for filmmaking (he even worked on the documentary film Derrida). But instead of making a film, he spent a decade writing a dense novel about a film that doesn’t exist. When House of Leaves was published in 2000, it immediately became a cult hit. In my high school, copies could be seen in the hands of all the cool kids. (When I told him this, he laughed and said that the cool kids certainly weren’t talking to him when he was a teenager.) It became a kind of shorthand for hip, young literary types, like a challenge: Did you understand it?

If you don’t already know, here is the best summary of House of Leaves I can muster: a guy named Johnny Truant lucks into an apartment after the old blind man living there dies suddenly. Once inside, Johnny discovers hundreds of pages of text, somehow written by the blind man (whose name is Zampanó), which describe—in elaborate detail, replete with footnotes, references, and quotes—the plot of a film called The Navidson Record. Though Johnny tries to find a copy of it, the film simply doesn’t exist. The Navidson Record is about a photographer named Will Navidson who decides to set up cameras all around his house to document his family’s new life. One day, he measures the inside of the house and the outside, and finds, disturbingly, that the outside is longer. Then, a hallway appears in his home that wasn’t there before. Then it begins to grow.

A summary of House of Leaves, however, cannot do justice to the experience of reading the thing. For one, the book is a miracle of design. All of Zampanó’s scribblings are recreated as accurately as possible—so if he wrote a portion of The Navidson Record on an envelope, the text appears on the page that way. And Johnny’s contributions come mostly in footnotes, so his story intermingles with the other. There are even fictional editors who occasionally comment on the project as a whole. The result is disorientation, but not of the nauseous sort, but more like a moment of unsteadiness before pushing on. And this is Danielewski’s phrasing, too, that his books are not flagrant disavowals of convention but “a very soft and steady push” against expectations.

Though House of Leaves launched Danielewski into the literary spotlight, and though he’s still incredibly proud of it, he now expresses some disappointment with the way fans obsessed over its enigmatic contents. “I saw people so invested in its own interior logic, that they were very satisfied to just stay within the book. Which was a great compliment, but I had no interest in writing sacred text, texts that would kind of lock one up into, you know, the world according to the book.”

This stunted insularity led him to his next project, Only Revolutions, a novel even more experimental and challenging than its predecessor. Published in 2006, it’s the story of Sam and Hailey, sixteen-year-old kids who don’t age and who can travel in time. The two teenagers take turns narrating the story (in invented, Joycean prose), but instead of, say, alternating chapters, both narratives occupy the same page, one right-side-up, the other upside-down. Only Revolutions is more than a title here; it is also an instruction: when reading it, you have to flip the book over (like a revolution) to continue reading. Along the edges of each page are the endless dates and significant historical events Sam and Hailey move through. It’s a hyper-poetic, impressionistic novel, and one that, for the most part, confounded its readers (though the National Book Award committee named it a finalist in 2006).

If House of Leaves kept readers contained in a house, Only Revolutions, Danielewski says, is “one of those books that depends on getting out. It’s centrifugal. Unlike the centripetal first book. And that proved very difficult. It does require a lot of getting out into the world, getting out of yourself, getting out of your own anxieties, your prejudices, really.”

My own experience of reading House of Leaves and Only Revolutions confirms this: the first felt claustrophobic, while the second seemed to shoot outward into an endless expanse.

He agrees, saying, “The house is absolutely limited, like the book. But it offers within its context this infinite labyrinth, whereas Only Revolutions—and I actually haven’t thought of it this way—offers you this endless space outside, but it’s also that the ego of both of them is textually and visually apparent on every page in the book itself. So you can either lock into Sam and Hailey, which is what many readers do, and that way it kind of frees you from the anxiety of the maze that surrounds you. In some ways, you’re on the outside of the maze in House of Leaves, and you’re in the center, if such a thing exists, of the maze in Only Revolutions. And they provoke different kinds of anxieties.”

* * * *

Anxieties, yes. His novels definitely provoke anxiety. But here’s an important question: beyond the formal innovations of Danielewski’s books, are they any good? Do they accomplish more than pure literary radicalism?

My answer is a big, sweeping yes. For one, I would argue that more than any other contemporary writer, Danielewski has blown the door wide open on novelistic experimentation. Unlike, say, the experiments of the modernists, who sought new ways to represent interiority, the mind, and the strange associative qualities of our existence, Danielewski’s incorporate complex verisimilitudes of everyday life, and by doing so adds a dimension to fiction it has never quite had before. Think, for a moment, of Vladimir Nabokov’s Pale Fire. That book is made up of a 999-line poem written by one character (John Shade) and endnotes written by another (Charles Kinbote). Nabokov’s use of academic forms, as revolutionary as it is, still allows the reader a basically linear experience, as least as far as the actual reading goes. Sure, one could read the endnotes along with the poem, but switching back and forth is not required. In Danielewski’s fiction—which features numerous fonts in numerous colors, footnotes as opposed to endnotes, all stuffed together on the same page—the forms he’s borrowing on are rendered with a perfectionist’s detail. The design, then, takes on more importance than previous novels, because it becomes inextricably linked to the narrative.

All of which means that Danielewski has shown, emphatically, just how much formal experimentation can truly enhance a narrative experience, that employing radical verisimilitude really does change the way we read, that “taking the reader out of the story” can have many advantageous effects, that, most importantly, the novel is not dead. His is a kind of permissive art, the kind that grants authors inspired freedom, like a landmark court case that’ll be referred to again and again as the years pass. Novels like Reif Larsen’s The Selected Works of T.S. Spivet, Marisha Pessl’s Night Film, J.J. Abrams and Doug Dorst’s S., to name a few, all owe much to Mark Z. Danielewski. His books are freewheeling adventures into intricate depths and wide expanses, and they’ve helped usher in a new era of the novel.

There is, of course, another way to see it. Some see his elaborate typography, his dueling narratives, and his inscrutability as mere pretension, as flashy design with little necessity. He’s also pun-happy: see his meditation, in House of Leaves, on “hallways” and “always”; or his various uses of “revolution” in Only Revolutions; or, in The Familiar, when Astair worries that Xanther has had another seizure, it comes out like this: “A(mother nother!) seizure.” So maybe his work isn’t ushering in any new epoch but in fact is hoping to conserve something historical and, in some ways, old-fashioned. Perhaps Danielewski and his contemporaries represent a last-ditch effort to reinvigorate the form, a final, desperate gasp of air for the dying novel. In this time of generalized anxiety about the “future of the book,” Danielewski and co. do more than simply celebrate the novel as object—they make its physicality a vital component of the story. You can’t, in other words, read Danielewski in any other form than a solid, colorful book. Maybe, then, his work reaches back to the past as much as the future. But perhaps it is a fool’s errand, a vain attempt to revive something long dead.

But Danielewski himself is not as interested in these kinds of notions. At 49, he’s lost much of his youthful bravado. For instance, he describes the bookshelf on the wall of his Los Angeles home: “The books are broken down,” he says, “according to the characters in The Familiar. So that when I’m working on those characters, I’m looking at the books that they read. And I understand, then, that that’s their vocabulary. If I’m working on Astair [Anwar’s wife, Xanther’s mother, and a therapist], I can look here and see The Writing of Disaster by Blanchot, I can see Stiegler’s Technics and Time, I can also see James Hillman’s Animal Presences. And even as I’m looking at them now, they bring out all of the kind of like strange vocabularies that those characters have.”

But when I respond by suggesting a kind of intertextuality going on here, Danielewski’s quick to steer away from purely insular notions of fiction. “I thought it would be nice to think that these books quantify the compost out of which The Familiar grew, but that’s not really accurate.” Instead, he took the advice of one of his literary forebears: Thomas Pynchon. In his introduction to Slow Learner (the most autobiographical thing the reclusive Pynchon every wrote), Pynchon describes the “claustrophobia” that was hindering his early work, and how he needed to “stretch, to step out.” The Familiar, for Danielewski, “was about getting out of the house, it was about getting out into the world and starting to really talk to people and see people. So for this it meant traveling to Singapore and spending a lot of time with people from various gangs. It also meant sitting in an interrogation room with an LAPD detective, and that kind of stuff.”

“If I felt that this was just the text talking to text,” he concludes, “then I would consider it a failure.”

Nor is he interested in using all these techniques to represent reality, a term he finds “faulty.” “You can sort of see them littered throughout our linguistic history,” he says. “These words that are kind of vacant, and are used to hold things that we just don’t understand, whether it’s the name of gods, whether it’s the ether, and reality is one, you know, it’s easy to say, it’s kind of nice on the tongue, but it’s really kind of as meaningless as fuck these days. It’s so divorced from any useful or operative definition, it’s as much a kind of support beam in the sound of a sentence.”

The Familiar, then, is the result of much experience—with the reception of his previous books, with going out and exploring the world, with getting older and less certain. “If we were having this conversation 15 years ago,” he’s quick to point out, “when [House of Leaves] was coming out, I might have told you what I thought the lightning in the bottle was, so to speak. But now? I don’t really know. I don’t know what makes that book hum.”

And what about The Familiar? What makes it hum? For one, it fits somewhere between House of Leaves and Only Revolutions: “The Familiar then, it strikes this balance of, at least for me, that it is as self-contained as it is ever-opening. And that’s important for me to continue with.”

But there’s something more than this, something about the miasmic polyphony of the everyday: “We’re more aware these days of how even those voices are commingling, they’re resonating, they’re harmonizing—or they’re just, you know, contradicting or creating all sorts of dissonance with other voices. And how do we look into that murmur? You know, do we strip away everything that we don’t like so we can find a song we like or do we change the way we listen? And embrace a sound that may be strange to us but the more familiar we become with it, the more we can embrace a larger totality of this world we live in, this time that we occupy.”

This notion—of either finding a song we like or changing the way we listen—sticks with me. It seems to challenge something deep in me that’s always been there but never been articulated: how much of our experience with art, with people, with life, is dictated by our comfortable expectations? By our search for validation and confirmation? How much could we learn, how much could our perceptions be expanded, if we could only just change the way we listen. And this, truly, is The Familiar’s most evocative achievement—these are voices speaking to each other, not texts. Xanther and Anwar and Luther and Cas—they’re brought to life through their own idiosyncratic rhythms, and when integrated so harmonically with other voices, the book becomes a symphony to life’s familiar strangeness, which we’ll always hear if we just stop and listen.

And then, of course, he’s off on another tangent: “In the end, however you break it down—and it’s important to break it down, I’m all for analysis—there’s a sense that readers understand again that they’re cheating time, that there’s a kind of energy, a velocity and there’s a density—all of it. And there’s kind of a transparency. All at once on the page. And whether they read the whole thing or not—they go on the ride or they don’t—there’s this sense that it’s living. Or, it’s alive with their own promise. Maybe that’s it. It’s not that the book is living, but in the presence of the reader, the reader feels suddenly alive to her own promise. And that’s what a book can awaken. And I think the only way that that happens is if the writer is really putting it on the line. I think that’s it. You know, you just sense it. You sense, like, Oh, all chips are in. This is where it’s at.”

Now, he says, “whether you like it or not is sort of immaterial to me.”

I’m just about to respond with some brilliant insight about the relationship between author and reader when he suddenly says, “I have three more minutes for this conversation. I have to get back to Volume 2.”

Then, after some obsequious formalities, Mark Z. Danielewski’s gone, back into the forest, while I’m still out here, like all the rest of us, just a little behind, in the downpour.

Jonathan Russell Clark

Jonathan Russell Clark is the author of Skateboard and An Oasis of Horror in a Desert of Boredom. His writing has appeared in the New York Times, L.A. Times, Boston Globe, and Esquire. He's also a columnist for Tasteful Rude.