Deus Ex Machina with a Credit Card: On the Pleasures of Writing Supremely Rich Characters

Mikaella Clements and Onjuli Datta Consider Our Literary Fixation on the Very Wealthy

During the summer of 2016 we had been married for a year and barely saw each other. The two of us were attempting to scrounge up the funds we needed to move to Berlin, working all the time, saving desperately. The Brexit vote cast a shadow down through July and August, while Trump’s campaign gained steam, and it felt like everything was teetering on the brink. One of us worked six days a week at four different marketing gigs and the other was working night shifts. One of us left the house at eight am. The other didn’t get home until two in the morning. We saw each other in the sleepy crossover and, if we were lucky, on Sundays. Somewhere in the midst of the exhausted daze, we began to write a story about two rich people falling in love.

It took time—the literal passing of years, and then the shock of 2020’s rupture in ordinary life—to consider this early sleepy impulse, the way we seemed to fall into the allure of the rich, not least because we didn’t start off writing about wealth. We wanted to write about fame: the public performance of celebrity, what it meant to play out a love story—and then actually fall in love—in front of an audience. But the intersection of wealth and fame can sometimes feel like a straight line.

Famous people are often wealthy, and wealthy people are often entertaining. We love to watch people performing their wealth, be it highly self-conscious symbolism (last week I was in my other other Benz) or the strangely addictive mundanity of the Kardashians. Fiction is no different: Gatsby’s literal wealth might have come first, but the mysterious figure throwing dazzling parties seems to be the true allure of those riches. It’s why so often we see rich characters through the eyes of the hungry voyeur, like The Secret History’s Richard Papen or Alan Hollinghurst’s young interloper in The Line of Beauty. Even Luster’s Edie offers a nod to the trope—our voyeurs don’t have to like their rich people to be fascinated by them.

Because shit, that siren call of money. Like our favorite characters, it’s hard not to find yourself seduced by it. Think of Elizabeth Bennet, first watching the “large, handsome stone building” of Pemberley coming into view and thinking “that to be mistress of Pemberley might be something!” Or the opening of Kevin Kwan’s Crazy Rich Asians, where a hotel’s racist general manager is vanquished by simply buying the hotel.

The fantasy of ease and importance is a potent one, sometimes more so than the symbolic fantasy of luxury yachts or designer clothes.

The rich revenge fantasy (“Big mistake. Huge.”) is just one option in a catalogue of jet-setting pleasures. Writing—and reading—about the super-rich opens the same imaginative doors that being rich opens in real life: yachts on sparkling ocean waters, expensive whiskey and extravagant meals, penthouse suites, designer clothes, commodity as aesthetic and vice versa. It’s easy to put your wealthy fictional characters in beautiful locations, so in that sense the escapism is very literal.

And for the most part, writing about wealth means sweeping the humdrum of 40-plus-hour work weeks to the side, allowing us to spend all our time on our characters’ inner lives and personal dramas. Even if a character’s wealth comes from work, it’s rare for us to see the actual earning of riches. We don’t care about the ins and outs of Christian Grey’s… holding company, right? We want to see our characters spend, not save.

The freedom of writing about a rich person is often around convenience. There are so many concerns that might not cross a rich person’s mind—and so it’s a kind of deus ex machina with a credit card. Your character needs to get to New York by midnight? No problem, put them on a private jet. Need a grand setting for your grand gesture? Hire out the Empire State Building. It works the opposite way too. It’s easy to raise the stakes when your characters are VIPs, when their decisions have the potential to change the fortunes of thousands, or when they will reverberate into pop culture consciousness. This fantasy of ease and importance is a potent one, sometimes more so than the symbolic fantasy of luxury yachts or designer clothes. Symbolism itself seems on tap with the champagne; with unlimited funds at your disposal, you can let your characters act out their dramas on as grand a stage as you can imagine.

Whenever we were worn down or anxious or bored in that hellish 2016 summer, we slipped into our novel, finding refuge in marble bathrooms, expensive wines, a private stretch of water as though the ocean, too, was something that we could own. Writers tend to be possessive, magpie-like, seizing that anecdote, that view, that annoying guy at a party and finding a new home for them in their work. Writing about wealth only increased our level of theft, claiming new experiences and possibilities we’d never dreamed about in real life. The first third of our novel takes place in Saint-Tropez, a celebrity wonderland neither of us have ever seen. We liked the name and the connotations of glitz and sun, we knew what it looked like in our heads, and we felt no real sense of responsibility about making the location true to life. Our priority was never for a millionaire to read the book and think this is accurate—it was for people like us, doing shift work or dull office jobs, to feel swept away.

But without meaning to, we brought our tensions and anxieties with us into the glittering world we’d made for escape. Although we’d mostly finished the novel by the time the pandemic hit in 2020, we were still working on some last edits and it was a joy to escape into another world—with frequent flights, and crowds, and Europe at your doorstep rather than locked down. Yet following behind at baggage control was our own uncertainty: is now the time for escapism, especially about the wealthy whose very existence necessitates others living in poverty? Did it make sense to be so invested in a fictional love story while the world went to hell around us? Why, as one of our fathers irritably asked, did we have to write a story about rich people?

The sting in the tail is part of the pleasure, part of our possessive demand when we take wealthy characters into our own hands, either as writers or readers.

Of course, we didn’t have to. We wrote The View Was Exhausting simply because we wanted to—for what wealth could say about our characters, for the fun we could have in glitzy hotels and secluded mansions, for the convenience and the glamour. Along the way, our own hurts and fears and desires crept into the idyllic, shimmering world, because escape isn’t so easy. Look at F. Scott Fitzgerald’s giddy, decadent version of the 1920s, scampering away from the 1918 influenza pandemic, each lavish cocktail with its own dangerous aftertaste. Or the bright young things in Evelyn Waugh’s Vile Bodies, dancing from the catastrophe of World War I into “Victorian parties, Greek parties, Wild West parties, Russian parties, Circus parties, parties where one had to dress up as somebody else, almost naked parties in St John’s Wood, parties in flats and studios and houses and ships,” nearly tripping with weariness on their way to the next.

The sting in the tail is part of the pleasure, part of our possessive demand when we take wealthy characters into our own hands, either as writers or readers. Show me the mansion I’ll never live in, the car I’ll never drive, the dress I’ll never wear. Give it to me; I’m the one who’s really paying for it.

___________________________________________________

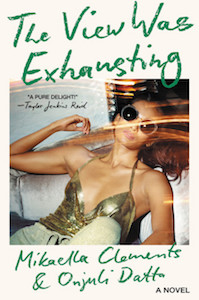

The View Was Exhausting by Mikaella Clements and Onjuli Datta is available now via Grand Central Publishing.

Mikaella Clements and Onjuli Datta

Mikaella Clements and Onjuli Datta are the co-authors of The View Was Exhausting. Mikaella's writing has appeared in the New York Times, the Guardian, Hazlitt, Catapult, and more, and she was shortlisted for the 2019 Galley Beggar Press Prize and the 2018 Bridport Short Story Prize. Onjuli's work has been published in The Billfold and Daddy magazine. Mikaella is originally from Australia and Onjuli from England; they are married and live together in Berlin.