Defying Classification: An Introduction to Southeast Asian Speculative Fiction

Victor Fernando R. Ocampo Recommends the Best of a Growing Genre

The year was 2013 and I had just started on my writing journey when I managed to attend a lecture given by the award-winning writer Ken Liu in Singapore. During the Q&A I asked him “What would it take for Southeast Asian speculative fiction to be widely read?” His answer was both simple and very difficult: “Build more centers.”

Southeast Asia—that part of the world that’s south of China, southeast of the Indian subcontinent and northwest of Australia—is home to over 655 million people with hundreds of indigenous cultures and complex, diverse ethnicities, but its literature (speculative or otherwise) is still lesser-known to West-centric readers.

Thankfully, this is changing. During the last decade, authors and artists within the ten countries that make up Southeast Asia (Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, The Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Timor Leste, and Vietnam) have begun to champion and celebrate their own home-grown “literature of the Fantastic.” In cities like Kuala Lumpur, Manila and Singapore, speculative fiction works of all stripes routinely appear in local best-seller lists. There are now books full of ancient pontianaks and vicious manananggals, fin de siècle bioterrorist gardeners, and even sentient spaceships incubated in the wombs of courtly Dai Viet women. A new center of literature is developing.

These stories have now even crept into the consciousness of the West, with works like Disney’s (flawed but well-meaning) Raya and the Last Dragon and Netflix’s adaptation of the Filipino graphic novel Trese enjoying some measure of popularity. A number of the individual authors mentioned below have now also been published in the United States, London, and elsewhere.

Southeast Asian speculative fiction is simply the totality of all genre work in fantasy, horror, and science fiction (as well as their respective sub-genres) produced by writers in or from the region. It’s hard to speak of a single, uniquely Southeast Asian identity (or even a coherent Southeast Asian aesthetic, for that matter)—to me, this plurality that defies easy classification is a very good thing. Each writer’s worldview, rooted in their specific culture, creates a different universe for readers to explore and appreciate. It clearly demonstrates that not everyone shares the dominant and hegemonic Western, majority white, cis-gender, and individualistic culture that strangles everything else.

This is where I suggest you can begin your journey.

Ed. by Jason Erik Lundberg, Kristine Ong Muslim, and Adan Jimenez, Lontar: The Journal of Southeast Asian Speculative Fiction

Published between 2014 and 2018, the ten volumes of Lontar represent the gold standard of Southeast Asian speculative fiction. “Lontar” is the Indonesian word for a bound palm-leaf manuscript, which is among the oldest forms of written media, dating as far back as the 5th century BCE. As such, this ancient form of writing is the perfect symbol for the curation of Southeast Asian speculative fiction. The journal’s contributors include writers and artists who have won major literary and genre awards such as the Hugo, Nebula, Palanca, and Seiun Awards, as well as the Singapore Literature Prize. Some of the standout stories include “Love in the Time of Utopia,” a story about an alternate Kuala Lumpur by Zen Cho; the haunting “A Field Guide to the Roads of Manila” by Dean Francis Alfar; “The Moon Over Red Trees,” a story of treachery and exploitation in colonial Indochina by Aliette de Bodard; Neon Yang’s “Mother’s Day,” a uniquely Singaporean response to a viral outbreak; Alyssa Wong’s “The Fisher Queen,” a story about fishing for mermaids in the Mekong River; “Ink, A Love Story,” a cautionary tale of writing one’s perfect lover into existence from Vida Cruz; “Satay,” a post-apocalyptic kampung story by Wayne Rée; and “The Feast,” a short horror comic about manananggals by Budjette Tan & Kajo Baldisimo (of Trese fame).

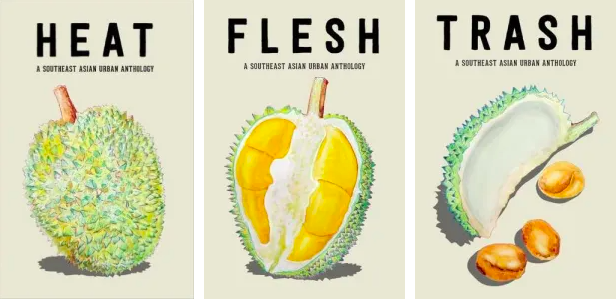

Ed. By Khairani Barokka and Ng Yi-Sheng, Cassandra Khaw and Angeline Woon, and Dean Francis Alfar and Marc de Faoite, Heat, Flesh and Trash

Heat, Flesh & Trash by cult Malaysian publisher Fixi Novo collected and showcased stories that it called “Southeast Asian urban fiction.” The triptych of books evoked the process of eating a durian, that iconic Southeast Asian delicacy known as the “king of fruits” (you felt its heat before you consumed the pungent flesh, before finally disposing of the skin as trash). While not all the stories collected are speculative in nature, each one dwells on themes and issues unique to living in Southeast Asia’s mad, tropical climate. Some of the best works include “Tinder,” Gabriela Lee’s story about a girl who can burst into flames; “Appliances,” Nikki Alfar’s off-beat science fiction tale about robot girlfriends; “Back To Life,” an intimate story about a psychic healer by O Thiam Chin; and “Dimsum,” Christine V. Lao’s dark tale that unexpectedly tackles both dimsum and demons.

Ed. by Joyce Chng and Jaymee Goh, The Sea is Ours: Tales from Steampunk Southeast Asia

The Sea Is Ours is a unique anthology that features twelve stories blending the retro-futuristic steampunk aesthetic with alternative history and magic realism tropes, inspired by Southeast Asia’s diverse peoples, legends, and geography. While the very idea of steampunk might bring to mind images of Rule Britannia and imperialism, this very post-colonial collection subverts that image at every turn. Noteworthy stories include “Chasing Volcanoes,” Marilag Angway’s story about a volcano-powered airship and her cynical captain; a feminist demon tale called “The Last Aswang” by Alessa Hinlo that pits local magic against colonialism; Robert Liow’s “Spider Here,” a hard-SF adventure with a suicide bomber, illegal fights, and a disabled schoolgirl protagonist; Olivia Ho’s story “Working Woman,” about an underworld detective tracking an experimental clockwork woman; and most especially the haunting “The Unmaking of the Cuadro Amoroso” by Kate Osias, a beautifully written tragedy about a quartet of lovers who seek vengeance as martyrs against an imperialist war machine.

Ed. by Jason Erik Lundberg, Fish Eats Lion

Fish Eats Lion was the first collection of literary speculative fiction to be published in Singapore. It assembled 22 stories that ranged from science fiction and fantasy to absurdism, police procedural, fairy tales, steampunk, pre- and post-apocalypse, political satire, and even a lyrically written tale of an alien first contact (the amazing “The Story of the Kiss” by Stephanie Ye, which unfortunately is included only in the first print edition). Other highlights include Ng Yi-Sheng’s “Agnes Joaquim, Bioterrorist,” a steampunk take on a biologist trying to change the world, and Shelly Bryant’s “Rewrites,” where research into synthetic biosystems takes an unexpected turn.

Ed. by Zen Cho, Cyberpunk Malaysia

Malaysia’s first English language science fiction anthology assembles 14 cyber-punk–inspired stories all written by local authors or who are of Malaysian descent. The term “cyberpunk” refers to an aesthetic defined by the contrast between high technology vs. the grittiness of characters in the fringes of society. The book blends Malaysian cultural sensibilities (e.g. tudung-wearing cyborgs) and possible near-future scenarios while tackling some deep themes like censorship/moral policing and the exploitation of migrant workers. Standout stories include Adiwijaya Iskander’s “Twins,” where a robotic bounty hunter and his rivals pursue a pair of bioengineered siblings through jungle ruins, and Zedeck Siew’s “The White Mask,” where animated street art starts murdering graffiti artists.

Ed. by Dean Alfar and Nikki Alfar, The Philippine Speculative Fiction Series

Published between 2005 to 2016 (with the 11th volume a “best-of” collection covering the first five years of the series), these eleven volumes comprise a landmark work that first introduced Philippine readers to the term “speculative fiction.” The series has also nurtured many Filipino authors who have since gone on to make their mark internationally. Iconic stories include F.H. Batacan’s “Keeping Time,” where most of Earth’s water supplies have been contaminated with an enzyme that caused people to catastrophically lose weight; Andrew Drilon’s “The Secret Origin of Spin-man” a tale of comic books, brothers, and loss; Charles Tan’s “A Retrospective on Diseases for Sale” is about a company that sells programs that could psychosomatically induce real diseases in people; “Breaking the Spell” by BSFA-nominated Rochita Loenen-Ruiz, is a lyrical fairy-tale pastiche with Filipino elements; while “Parallel” by Eliza Victoria masterfully plays with the genre trope of having the ability to travel to parallel universes.

Southeast Asian speculative fiction holds a vast repository of ideas that deal with the imaginative and the unfamiliar in a uniquely regional way–specifically ideas rooted in the tangled history of the region and each country’s unique literary tradition. A new center for the literature of the fantastic is developing and I believe it’s time for everyone to take notice.

____________________________________________________

Victor Fernando R. Ocampo’s The Infinite Library and Other Stories is available now via Gaudy Boy.

Victor Fernando R. Ocampo

Victor Fernando R. Ocampo is the author of the International Rubery Book Award–shortlisted The Infinite Library and Other Stories, a collection of speculative fiction available from Gaudy Boy. Ocampo is a fellow at the Milford Science Fiction Writers' Conference in the UK and the Cinemalaya Ricky Lee Film Scriptwriting Workshop in the Philippines, as well as a Jalan Besar writer-in-residence at Sing Lit Station in Singapore. Originally from the Philippines, Victor currently resides in Singapore.