Get there: the day after Jay committed suicide, Coral had a brunch date with her friends and did not cancel. We believe in confronting danger unblinking, face to the flames, teeth bared to bullets. We do not wince at pain unless that is the practice of the hour. To wince is to acknowledge the potential for defeat, five for flinching. We are unsure where the danger fell for Coral, in the face of her friends or in the judgment at her absence. Coral had stayed at Jay’s apartment and did not head to her home in La Brea until after sunrise. She owned a bungalow with a yard in one of a thousand overpriced neighborhoods in Los Angeles. The sky was bright and blue, light reflected from everything that morning, the shine in the washed cars of her neighbors, the glimmer of dew on the shrubs. Finger succulents, velvety and swollen, which everyone used to replace grass, studded the front lawn. It was a beautiful day.

Where she was: Coral approached Il Fornaio feeling as if her throat were turning to steel, all the veins and muscles hardening, the blood squeezing through clogged plumbing. It was the same feeling she had after eating a family-sized bag of chips. She wanted to expel whatever was in her body through every possible exit port, but relief was not possible. The thing inside her was not going to come out. It was hot. There were misters running at the entrance under a green awning. Coral walked through the veil of mist and jumped back as if spit on. She remembered that the devices were supposed to be a luxury. She walked through a forest of people, big people and small people at tiny tables with barely enough room for their bread baskets, saucers of herbs and olive oil, and eighteen-dollar mimosas (not bottomless). The friends were on the patio in the distance. One waved her over. A waitress backed into her suddenly. Liquid hit the top of Coral’s left foot. A dog barked, then was silenced. The restaurant was flooded with the clatter of voices, so many that it seemed quiet. So much noise that there was nothing to hear at all. Coral suddenly realized it was all meant to be pleasant.

Where she wanted to be: The friends appeared, talking all at once, greeting her all at once, their heads seeming to spin like coins, she was unable to discern a face or mouth, just the knowledge that there was one amid the blur. Coral wanted to be somewhere quiet where there were no heads unwinding like rubber bands; somewhere her own throat felt soft and pliable and she could turn her neck without pain; somewhere with water stretched out in front of her or heavy in the sky above, about to be squeezed out; somewhere even the insects knew not to make too much of a sound, because something special was about to happen again, something they didn’t know they were looking forward to until it arrived and now there was nothing more important anywhere in the world. The unique relationship to water among the living was incomparable to any other. It was more than sex, murder, food, or faith. It was their god and their whore.

Who she was: Like most people less than fifty years old and more than nine, Coral was a curated exhibit, carefully constructed in the presentation of self. First, she wore dresses because children in the 1980s were treated like peach pits where the body was the seed and the resulting fruit a voluminous array of ruffles and lace. Then came two decades of Sunday services in a Baptist church. Then came various declarations of gay followed by estrangement from her parents, mostly her father, the burial of those parents, and the duplicitous sensation of suffering and relief forever after. Ultimately, Coral met all expectations of gender, race, politics, education, and diverted from those expectations only when appropriate for a change in audience. She did

so consciously and subconsciously, as was the norm. In a slight deviation from normal, Coral became a successful artist, writing and drawing fantasies into reality, and luckily found more audiences with money as well as a curious community of peers, competitors, and patrons.

Who they are: The friends would’ve eaten her. If promised anywhere from a hundred to a million dollars for tearing off a bit of Coral’s flesh and swallowing it down, those friends across the table with half-chewed omelets and drops of vodka and tomato juice lingering under their tongues would choose the money. In the Clinic for Death from Loneliness, we study the idea of friends. We distill friendship to the fibrous root where people have no expectation except time; it is easy; there are no transactions, no obligations, just memories and the desire to do it all again one more time. Sometimes blood families can be friends but not always. We’ve concluded that friends are discovered through chemical compatibility, like lovers but with less genital contraction or bonding through experiences, especially trauma and triumph. A single devastation or victory can sustain a friendship for a lifetime. One of the spinning heads asked Coral a question in a low voice, as if it were a secret. How are you, she asked. Coral thought about the answer briefly, the one she would give and the one she would keep. My brother is dead. He was not dead and then he was dead. Who are you and this place? Why have you kept me here? The head stopped spinning and Coral could see eyes, dark brown and alert, the eyeshadow, low lids, signs of ptosis from aging, and a mustache painted in foundation. Bad date, Coral actually said, or good one. They’re all the same to me. The head spun again, disappearing into laughter.

She had slept on her brother’s stripped mattress in the humid apartment, waiting for something.

Who she wanted to be: Present. Coral wanted to be acutely aware of her feet on the brick patio, the drying drops of liquid on the top of her foot, the individual conversations taking place around her and in front of her, the person she used to be and the person she would be from then on, and to be able to choose between them like items on a drive-thru menu. Today she would be seventeen-year-old Coral, drinking wine coolers with friends in the back of a Toyota coupe before going to the mall to steal cheap jewelry. Tomorrow she would be Coral seven years from now, safely through the grieving process and managing an almost happy life.

Who she wanted them to be: She wanted the friends to be themselves but not with her. Let them exist where they needed to but not with her. She wanted them blind, transformed into beautiful bats with too much lip gloss, hanging upside down from the restaurant ceiling, free to shit on the other patrons and gnaw on handfuls of overripe plums. She wanted them to be that kind of happy, if that kind of happiness were possible.

Who she would be later: Later, Coral would be a fish, when the force of death has dismantled the atoms and sent them into the bellies of other things more than just a few times. First she would suffer, then wonder, then for a brief moment be healed, then start over.

A phone rang. The spinning heads looked at Coral’s bag. The ringtone was odd. It was Jay’s phone.

Jay’s phone rang again and a plate of ahi tuna tartare appeared under Coral’s face. She didn’t remember ordering it, and no one seemed alarmed. Coral excused herself to the restroom.

Texting: Good restaurants have bad restrooms. It has been documented. It is a fact. In a good restaurant the restroom is small and poorly ventilated. The line is always long and full of terror. People are not able to do more than one thing very well at any given time.

The terror comes from not just waiting but being alone with one’s body and thoughts in a hallway too cramped to lift an arm without touching someone’s shoulder or ass. Coral seized Jay’s phone and let the vibrations of it roll through her palm a few more times before opening the messages.

Kai: You’re a no show! Never in nineteen years bro what the fuuuuuuuck

Kai: Im worried what’s up

Kai: is it K? She cool?

Kai: Vicki brought in Rjay but she flipping out threw half the smoked sausages away in the break room lol

Kai: yooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooo

Jay: I’m in the hospital.

All that fucking punctuation, Coral said aloud.

Jay: my foot is smashed and had to have surgery

Kai: oh shit bro you sound bad you shdilsai sksldiof ksiewoic

nwiocnv alsienf Vicky wont iandios hgh wes h aohs duakbn

Kai: vodiuah doaf how long ueshoudhf ouenbs

Kai: aweh xncow ealzosidn better bnusbbud bfus

The job: Coral lost her language-translation energy again as the air became more carbon dioxide than oxygen around her in the bathroom line. She began to scroll through past messages with this Kai person to understand many things. She learned that Jay possessed terrific grammatical sense, whereas Kai had almost none. There was a running joke/obsession with sausages in the break room that Coral thought might be a euphemism for something male and sexist, but knowing Jay she believed it was sincerely about food. Coral felt compelled to understand Jay’s job better, an essential tactic for infiltration of enemy territory.

Line at the restroom: The line for the restroom moved by a single individual. Everyone shifted forward with the assumption that more than one person would move along, but that assumption was replaced with despair and resignation. When cattle were slaughtered for food, the process involved arranging the animals in a curved or zigzag line because the end of the line was the end of their lives, and it was important that none of them could see that far in advance.

Small talk: Coral put down her phone and looked up to find a pair of eyes fixed on her. The body those eyes were attached to had an awful intention. It wanted to talk to Coral, and she could’ve looked away, could’ve willed herself into a coughing fit that everyone would back away from politely or otherwise. Coral had no defenses at the ready, so would take the first blow unblocked.

Is it a birthday? Your friends are so happy at the table.

Yes, Coral replied. Not mine.

Coral often lied to strangers. During small talk with anonymous individuals you can be anyone. Most people lived unconscious lives, surrendering their thoughts to the inventions of the day. Thinking was dangerous. Thinking as someone else would think was something other than dangerous: risk-free, yet thrilling.

The stranger took a pose of lamentation and said,

They don’t sing for birthdays here.

Thank God, Coral declared.

The stranger laughed. Coral smiled.

My birthday is in the winter, Coral said.

Holiday season. That’s great.

It was like a double party every year as a kid. Christmas pie and birthday cake. Some people hate it.

Oh, I know. My daughter’s is in December. She’s always cranky. In fact, she really is always cranky.

Oh no.

Yes, she’s having surgery this month too.

Is it serious?

No, no, it’s not at all.

I had a thing with my liver, Coral lied. They did a biopsy.

She liked this twist in the conversation very much.

Oh my gosh, everything good?

Well, it’s to be determined.

The stranger reached for her phone. Coral had inadvertently ended the conversation by threatening further discussion of medical ailments with a woman that possessed the emotional capacity of a fern, craving only sunshine and moist air. Coral felt almost victorious and very, very alone. She wanted more.

What was your daughter’s surgery?

Vicious. In an unsolicited attack Coral returned to what was known as small talk with the wounded woman in line. A man approached the hall, observed the density of bodies, and immediately retreated.

She left the country for the procedure.

Oh, for a specialist?

For a better price. BBL.

BBL?

Coral feigned ignorance. She wanted to hear the words. She wanted to be above vanity. She wanted to be above the bone and tissue and blood that gravity pulls so relentlessly to keep them knotted to the dirt. The woman aged suddenly. The tendrils of blond hair frosted her brow and cheek. The rouge seemed heavy and unabsorbed. Lines like the Mississippi Delta branched out from the points of her eyes. She gestured to her ass.

Oh!

Mmm-hmm.

Jay’s phone buzzed again and Coral gave it her attention. The woman whose daughter was having her buttocks enhanced sighed in relief.

Kai: when do you plan to be back?

Kai: Vicki been quiet now.

Jay: Tomorrow for sure

Kai: coo

Jay: have some get well flowers ready

Coral stared for a minute until the phone turned black in silent mode. Flowers? she thought. Fuck. Coral checked the message list and saw four unread texts from Vicki. The line moved. She wanted to say more. She had more to say. She looked for the woman, but she was next and the door opened. Coral reached for the woman to tap her on the shoulder to say, My brother is dead today. I’m not used to that, and I don’t know anyone to tell. All of the women at my table are strangers to me and I’ve seen their faces for years and years. I knew better people once maybe, but I did not keep them or I was not kept. How do we get to places like this? Can we go back the way we came and begin again? Are mothers always thinking of their daughters like you do? What is that like? How do you not implode from being that in love?

Coral looked behind her to the line of tense faces all suddenly gazing her way at once, and for a moment she felt transported to a stage speaking before a hundred guests, all of them brilliant and gorgeous as half-gods, suspended out of time, peering into the edge of the universe, waiting for what was promised, for salvation, for mercy.

__________________________________

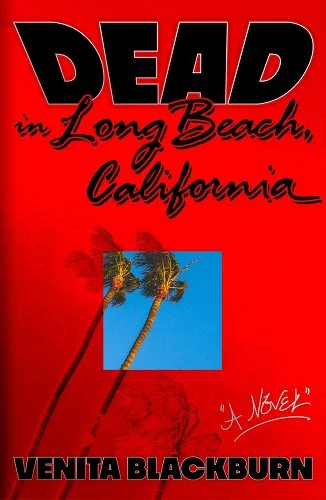

From Dead in Long Beach, California by Venita Blackburn. Published by MCD/FSG in January, 2024. Copyright © 2024 by Venita Blackburn. All rights reserved.