David Suzuki on the Urgency of Scientific Education in an Era of Climate Emergency

"It is clear that reason and facts alone no longer suffice to move people and society to action."

When artist Miriam Fernandes approached the legendary eco-pioneer David Suzuki to create a theater piece about climate change, she expected to write about David’s perspective as a scientist. Instead, she discovered the vision and efforts of Tara Cullis, a literature scholar, climate organizer, and David’s life partner. Miriam realized that David and Tara’s decades-long love for each other, and for family and friends, has only clarified and strengthened their resolve to fight for the planet.

*

How can we convey an important issue in a way that people understand what it is, how it affects all of us, and what can be done about it? That is the challenge that I have grappled with for decades.

I was astounded at the speed with which scientists identified and isolated the COVID-19 virus, then sequenced the viral RNA and determined its mode of attack through spike proteins. Out of dozens of ways to try to stop the virus, a revolutionary method—using mRNA of the gene to specify a spike protein rather than the spike protein itself—has proved extremely effective at eliciting an immune response.

Nature is the source of the air we breathe, the water we imbibe, the soil that generates our food, and the energy in sunlight that fuels our bodies.

In the twenty-four-hour news cycle that rapidly burns through stories, media have been saturated with COVID-19 information, not for days or weeks but for over two years now. It has been an emergency, and media have treated it as such. In contrast, climate change was recognized in 1988 as a threat to human survival “second only to a global nuclear war” at an international conference on the atmosphere in Toronto, which called for a 20 percent reduction in greenhouse gas emissions over fifteen years.

That same year, the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) was established to be the most authoritative source of information. If nations had taken the target seriously, we could have completely avoided the climate crisis we are in today. Media failed to cover climate change with the same endurance and intensity as they did with COVID-19.

Year after year, scientific reports on climate change have taken on an ever-more-urgent tone, while the evidence of its impact—through massive forest fires, floods, drought, storms, and melting glaciers and icefields—has dramatically increased. But until recently, these weather events have been reported independently, as if they were not necessarily connected by the driving force of climate change. In 2018, a special IPCC report urged the world to avoid catastrophic temperature rise of more than 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels by reducing emissions by 45 percent by 2030 and by 100 percent by 2050. The day after the report was released, marijuana became legal in Canada and wiped away any further reports about the IPCC targets.

Nature is the source of the air we breathe, the water we imbibe, the soil that generates our food, and the energy in sunlight that fuels our bodies. And nature remains the only way that carbon can be removed from the atmosphere and sequestered. In 2019, the United Nations reported that the planet is undergoing a human-caused mass extinction of species, the repercussions of which are devastating in countless ways. Yet the day after the report was released, Harry and Meghan had a baby and obliterated further discussion of species extinction and climate change in the media. What will it take to evoke the kind of sustained emergency response and discussion that we saw over the COVID-19 pandemic?

That’s the question I have been pondering since 1962, when, after living in the U.S. for eight years to get my post-secondary education, I returned home to Canada to begin a scientific career in genetics. But that year, Rachel Carson published Silent Spring, which documents the impact of pesticides on the natural world, and it hit me like a thunderbolt. So I was swept up with millions around the world in what became the modern environmental movement.

Reading the book, I realized that scientists focus on a single part of nature, isolate that fragment, control everything impinging on it, measure everything within it, and in that way acquire powerful insights. But in the wider world, everything is connected in ways we barely understand. As powerful as science is, the very process of focusing on individual elements is the essence of reductionism, and it blinds researchers from the context within which that isolated piece of nature exists and interacts.

A flask, growth chamber, or even field plot fails to address that interconnectivity; when DDT was sprayed on farmers’ fields, rain, wind, and snow swept the insecticide into the air where it spread and flowed into rivers and lakes, and its concentration increased up the food chain until, in the shell glands of birds and the breasts of women, the pesticide was concentrated tens of thousands of times. Scientists only discovered “biomagnification” as a biological phenomenon by tracking down the cause of sudden huge declines in raptors like bald eagles.

When I arrived on campus, the University of Alberta was producing a television program called Your University Speaks, broadcast by the local CBC station on Sunday mornings. I was asked to do an exposition on genetics, and the producer liked it so much I ended up doing a series of eight shows. After a couple of programs had been broadcast, I ran into people who would tell me they had seen and liked the show. I was flabbergasted to find that anyone would watch television at that time of day and on Sunday, and that’s when I realized that television had become a powerful medium of communication.

We have to touch people’s hearts, to move people emotionally. That’s why the arts, especially music, have an important role to play in the environmental movement.

Popular media like the press have whole sections on politics, finance, celebrity, and sports, but they ignore the reality that the most powerful force shaping our lives and society is not politicians, the economy, athletes, or famous people, it is science as it is applied by industry, medicine, and the military. Consider that, when I was a child, my parents wouldn’t let me go to movies or public swimming pools in summer because they feared I might catch polio. Back then, millions died of smallpox, which is now extinct; there was no television, computers, cell-phones, satellites, plastics, organ transplants, or antibiotics. Scientists didn’t know how many chromosomes humans have, what DNA did, or how sex was determined. Science has transformed our lives and society since then.

I deliberately chose to popularize science as well as do research because I believe the general public has a huge stake in the consequences of science and technology and therefore should be literate enough to have an opinion on how these applications should be made or restricted, rather than allowing businesses, politicians, and military officers alone to determine the fate of new technologies. So I chose to use television and radio to explain science whenever the opportunity arose.

My hopes of elevating scientific literacy through television have been dashed by cable and the internet. With so much information available, most people choose to surf television and the internet to find people, sites, and programs that confirm what they already believe so they don’t have to consider the facts or change their minds. If they want to believe climate change is a hoax, that vaccines give others the means to control them, that Earth was created in six days by God, or that the planet is flat, there are numerous websites, often with “experts” with PhDs, devoted to validating these beliefs.

I have written books (many for children) and weekly columns, and I have appeared on radio, television, and podcasts. It is clear that reason and facts alone no longer suffice to move people and society to action. We have to touch people’s hearts, to move people emotionally. That’s why the arts, especially music, have an important role to play in the environmental movement. But most of my communication in the popular media has been one-way, not a dialogue or an in-person exchange of ideas. So when Ravi approached me with the idea of a play, I did not immediately dismiss it because I was intrigued by the possibility of a more intimate personal conversation with an audience, a conversation that might convey passion, fear, and love, emotions that are as important as facts alone. You can judge from this play whether I am right.

__________________________________

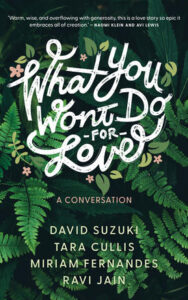

Excerpted from What You Won’t Do for Love: A Conversation by David Suzuki, Tara Cullis, Miriam Fernandes, and Ravi Jain. Copyright © 2022. Available from Coach House Books.

David Suzuki

Dr. David Suzuki has made it his life's work to help humanity understand, appreciate, respect and protect nature. A scientist, broadcaster, author, and co-founder of the David Suzuki Foundation, he is a gifted interpreter of science and nature who provides audiences with a compelling look at the state of our environment, underscoring both the successes we have achieved in the battle for environmental sustainability, and the strides we still have to make. He offers leading-edge insights into sustainable development and model for a world in which humanity can live well and still protect our environment.

He is familiar to television audiences as host of the CBC science and natural history television series The Nature of Things, and to radio audiences as the original host of CBC Radio's Quirks and Quarks, as well as the acclaimed series It's a Matter of Survival and From Naked Ape to Superspecies. David was the recipient of The Canadian Academy of Cinema and Television's 2020 Lifetime Achievement Award.